A Racist Dog Brain: Psychosurgery and Behavior in The White Dog

Solving Social Issues: Therapy or the Scalpel?

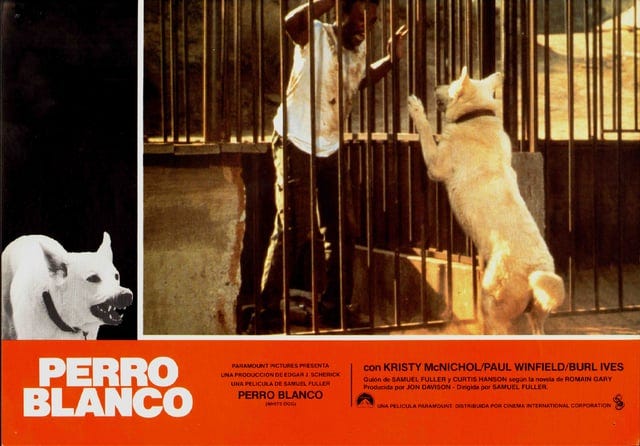

The movie White Dog is centered around interventions to rehabilitate a dog that attacks black people on sight. Its release (1982) was mired in controversy because of some alleged racist elements (Kasim, 1982). The NAACP claimed the film was trying to communicate a racist message in the dog’s actions, despite not having seen the whole movie. They even added the movie to their white list and opposed its production (Kasum, 1982). In contrast, Kevin Thomas, a journalist, maintained that the director's “concern for the evils of prejudice” is evident and successfully conveyed (Thomas, 1983). Nevertheless, the US release was postponed and limited because White Dog was shelved (Thomas, 1983). The production, Thomas concludes, is “disturbing,” but “it’s disturbing in the best, most concerned sense” (1983).

White Dog (1982) is a screen adaptation of a psychological horror novel by the same name, published in the 1970s. The book’s author, Romain Gary, claimed true events inspired the story, and he would commit suicide while the film was being made. Samuel Fuller joined as director and co-writer1. Previously, other directors, like Polanski, tried to adapt this book into a movie but failed (Thomas, 1983). The production takes significant departures from the book and takes a “far less pessimistic view of race relations.”2 Both Fuller and Paramount thought it should be shot as a straight thriller; however, Fuller insisted on keeping some of the “strong symbolism for which he is known” (Kasum, 1982)3. Samuel Fuller's White Dog is a bizarre work that explores psychological conditioning, racism, and instinct.

White Dog’s Plot

The White Dog tells the story of an aspiring young actress, Julie Sawyer, who accidentally runs over a white German shepherd and decides to take care of him while looking for the owner. She soon finds out it is no ordinary dog, as it violently attacks black people on sight. After an incident with a black female coworker during a production, she decides to retrain the dog.

Julie reaches out to renowned exotic animal trainer, Mr. Carruthers, who assures her that there is no solution for the dog, and urges her to sacrifice it. Mr. Keys, however, an associate trainer of Carruthers and a black man himself, steps in, determined to cure the White Dog. He tells Julie that he has twice come close to curing similar cases.

Mr. Keys' program goes with great difficulty, endangering those involved; yet, after some weeks, it appears to be working. Tragically, during a storm, the dog escapes and goes on the prowl for an innocent black person. The dog mauls a person near a church, and when Mr. Keys finds the victim’s body, he laments the death of another innocent black man. He now believes that curing this dog is even more critical.

After some arduous weeks of training and hopeful signs of change in the animal’s behavior, Mr Keys puts his program to the test. He places the dog, himself, and an assistant of his inside a cage, and waits to see the dog’s reaction with a pistol in hand. The dog approaches the black man aggressively, but stops a few meters away. Relieved, they all start to celebrate because the program appears to have worked. Then, the dog turns and jumps to attack Julie. In a split second, Mr. Keys shoots the dog, and it falls to the ground, where it gives out its final breaths.

Using the Knife to Solve Social Problems

White Dog offers an interesting perspective on lobotomy or psychosurgery, even though these are not central to the plot. The film strives to promote human tolerance and addresses a question at the center of the CuringCrime project: how has science-medicine affected how society tries to solve social issues? In this particular case, it contrasts social and surgical solutions. In the real world, some professionals thought psychosurgical interventions would help eliminate undesired behaviors in individuals.

One of the most ghastly medical interventions of the twentieth century is said to have been inspired by an experiment on chimpanzees. Egas Moniz, who won a Nobel Prize, is said to have developed the lobotomy after hearing about the results of an experiment presented by Yale researchers John Fulton and Carlyle Jacobsen at the Second International Congress of Neurology in 1935.

Fulton’s and Jacobsen’s experiment involved removing a significant portion of the frontal lobes of two aggressive chimpanzees. While it is often said that both chimpanzees became much calmer, in reality, only one of the two animals became much calmer. Impressed by these results, Moniz thought a similar operation could help some people. He operated on some of his patients and reported positive results, which inspired Walter Freeman to import this intervention into the United States.

Psychosurgery assumes that behaviors can be localized in specific parts of the brain and that operating on these parts can produce the desired change. This notion played a significant role in the development of shock therapies during much of the 20th century, and to some extent, contrasted with the environmental explanation for mental diseases. This environmental explanation emphasised the brain’s interaction with its environment and experiences.

Psychosurgery in the White Dog: Immoral Yet Powerful?

The feature introduced psychosurgery as a potential solution to the dog’s aggressive behavior towards black people. While Mr. Keys is describing what a White Dog is, and Julie listens with a mixture of shock and disgust, she asks him if it would be possible to remove this behavior from him, like cancer, using psychosurgery. This horror prompts viewers to consider how such interventions simplify and dehumanize people.

Mr Keys replies that he finds lobotomies to be inhumane, which is why he seeks to develop an alternative method to deal with this problem. Despite this objection, Mr Keys does not comment on whether the intervention would succeed. He believes the operation to be unpalatable, but he never suggests that it would not improve the dog’s condition.

Mr Keys' opposition to psychosurgery is moral rather than scientific and medical. This becomes clearer when Mr Keys is explaining his method while denouncing psychosurgery. He describes these surgeries as a “barbaric recourse.” He adds, “you see, Judy, I would like to develop a method, [and] within a matter of weeks, I will be able to erase that racist poison from him, permanently.” He later adds, “Twice I’ve gotten into the brain of a White Dog, and twice I’ve gotten close to cutting out that savagery without using a knife, and both times the experiment failed.”

This description, specifically the use of the knife analogy, as well as the expression of getting “into the brain,” highlights an understanding of the types of solutions that could work in these situations. Therefore, even if discussing and advocating for an alternative to a surgical intervention, the character's mental framework is one where psychosurgery can produce behavioral change.

In the real world, Dr. Percival Bailey, Director of the Illinois State Psychopathic Institute, had argued, in 1956, that lobotomy left “hecatombs of mutilated frontal lobes.” Both of these criticisms of psychosurgery also probe at a deeper question: what does it mean for a solution to work.4 Are these interventions intended to address the source of the problems or merely ameliorate their symptoms? Does it matter?

Lobotomy, Freeman sustained, “made patients into 'rather good citizens' even if they were less creative” (Kleining, 1985). He had argued that the most important criterion was whether patients could return to work. In the case of the film, then success could be measured by determining if the dog stopped attacking black people. Similarly, in A Clockwork Orange, Alex is shown to start an undesired behavior only for the conditioning to kick in and prevent him from carrying it out. Mr. Keys' reluctance to operate then suggests that there is something fundamentally wrong with merely treating symptoms, rather than the underlying causes.

How to Solve Social Issues: Conditioning & Behavior

The description of the White Dog also reveals a prevalent view in the character’s understanding of the world, emphasising the impact of the environment on the dog’s behavior. Contrast this worldview with more deterministic ones, whereby behavior is immutable, and thus solutions to social problems include the elimination or sterilisation of undesirables.

The description of how the environment influences the dog’s violent and racist behavior suggests that an organism’s environment can have a profound impact on its behavior. Mr Keys provides a possible explanation for why the dog behaves this way. He says, “find a black junkie who would do anything for a fix and pay them to beat that dog of yours since he was a puppy”, Mr Keys explains, “the younger the better, and as the dog grew up, those methodical beatings by blacks, planted the seed of fear in him, and that fear became hate, and that hate conditioned him to attack the color black before a black can attack him.”

This explanation highlights the idea of conditioning, meaning that it is due to impositions by the owners, that he develops a violent and aggressive personality inclined to attack people of color, as opposed to suffering from an inherent tendency to violence. The underlying argument is that racism is learned rather than innate, which implies we can resolve this problem.

Interestingly, the movie suggests that the fact that the cause was environmental does not mean that the cure has to be. Many experts recognized that experiences could cause mental disease (for example, shell shock) and that other conditions like schizophrenia could have environmental triggers. Yet, they still localized these experiences in particular parts of the brain and sustained that surgery would cure these patients.

White Dog suggests that racism is a learnt prejudice. In the film, black characters accept the existence of such animals as a brute fact, whereas white characters seem surprised. Mr Keys' insistence that the dog should be treated humanely encourages viewers to feel pity for people indoctrinated to be prejudiced rather than revengeful.

Conclusion

The White Dog offers two contrasting views of the origins of undesirable behaviors, perhaps even mental illnesses, through the existence of a racist dog. The movie suggests that these undesirable behaviors are learned, implying that racism and prejudice are indoctrinated rather than innate. It contrasts two possible solutions to such problems: psychosurgery and reconditioning or reeducation.

This production never questions the effectiveness of the surgical interventions, and the reconditioning of the dog is mostly unsuccessful. The dog’s treatment stops him from attacking black people, but the dog is killed while trying to attack a white woman, suggesting that the reconditioning did not fully work. It may have eliminated the dog’s fixation on black people, but it did not eliminate its violent tendencies.

The opposition to surgical interventions is communicated in moral terms, suggesting that they see the dog as a victim of its upbringing. Thus, even if such treatments were more effective, the story hints that they are inhumane and barbaric. The movie condemns psychosurgical interventions, which fits in with a series of other media that strongly criticize psychiatric interventions. The implications for human society are problematic, as it may mean that some people cannot be made to abandon their prejudices. Hence, change must come through changing children’s environments.

Secondly, in the movie, it is a member of the victimized group who not only recognizes that such perpetrators exist but also calls for them to be treated humanely. This preference for softer interventions by those victimized by the dog is meant to give emotional force to the argument that surgical interventions are barbaric.

If you are interested in learning more about the role of film and media in the history of science and medicine, check out our multiple posts on the topic at Curing Crime. Also, subscribe to receive all our latest posts.

Sources

Kasum, Eric. 1982. “White Dog” No Lassie Movie This. The Los Angeles Times, April 11, 1982. Calendar, p.18. https://www.newspapers.com/image/388304541/?terms=white%20dog

Thomas, Kevin. 1983. White Dog to Make a Belated Bow. The Los Angeles Times, Dec 30, 1983. Calendar, p. 1. https://www.newspapers.com/image/633580813/

Fuller was known to cast more minority actors than other directors, and initially, this made Paramount more comfortable with this problematic film. Fuller claimed he was among the first directors to give black actors complex characters. Significantly, Fuller had previously made The Crimson Kinomo (1959), which is one of the “few films ever to deal with prejudice towards Japanese Americans” (Thomas, 1983).

There are significant differences in the plot. In the book, Mr. Keys originally retrains the dog to attack white people rather than black people. The book thus paints a much more pessimistic view of racial relations.

The film touches on the use of conditioning and brain surgery to solve social issues. The film’s producer, Davidson, argued that he was “concerned” the film would be “judged” and misunderstood” even “before anyone has a chance to see it” (Kazum, 1982). He wrote that “racial prejudice is important to all thinking people,” and that removing these elements from the film would remove “the very thing that makes this picture worthwhile, which is the powerful plea for human tolerance” (Kasum, 1982). While I think this is an important topic that deserves a more exhaustive examination, it is beyond the scope of our project.

This is a crucial question both in the context of the film and our work. What do we want to achieve through interventions on individuals behaving in undesirable ways? Does merely eliminating the behavior in question count as a success? Do we care about root causes? How do we distinguish prejudice from other undesired behavior? Similarly, Jason Frowley PhD recently published a post asking readers to consider whether it makes sense to ask why a serial killer murders. Frowley demands that we consider what kinds of explanations would be satisfactory and why we seek them.

Wow - this sounds like quite a movie, and what an idea! I must admit, I've met some racist dogs in my time, it was very surprising, so I guess the idea is less off-the-wall than perhaps it sounds. I must add it to that list I keep mentioning, but which never seems to get much smaller. You are brave to step into the arena of race. I'd thought of writing a criminological review of Zootopia but decided against it because I just didn't want to get embroiled. This was another fine read. Keep it up, guys!