Lobotomy's Five Lives

Lobotomy has lived many lives, and we have made it our mission to study them.

Challenging as it may be to understand from our vantage point, the fact is that doctors, experts, and the public, were once enthusiastic about lobotomy and its potential to cure a series of mental diseases. Historian Jack Pressman brilliantly demonstrated that rather than seeing lobotomy as an aberration, we ought to recognize that historical actors genuinely believed in its potential. In short, this post is a collection of sad stories about well-intentioned efforts to solve a social issue through medical interventions. Lobotomy has lived many lives.

In some sense, Curing Crime owes its existence to lobotomy’s popularity in the early 20th century. After all, contemporary caricatures of lobotomy’s history, and past efforts to eliminate criminal tendencies through surgery is what first got Christian thinking about these subjects. He encountered these issues while taking a class about Narratives of Mental Illness.

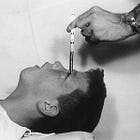

Lobotomy’s inventor, Egaz Moniz, was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology/Medicine in 1949, for the use of lobotomy to treat certain psychoses. Shortly after Moniz introduced lobotomy, Walter Freeman tried the procedure in the United States. Unlike some modern characterizations, Freeman was a highly respected physician. After being frustrated by frontal lobotomy, he invented a new technique that perforated the eye socket to lobotomize the patient. His zealous advocacy of lobotomy worked because he offered a plausible and medical solution to an existing grave social problem. The following article reviewed a book about Walter Freeman, and contextualized why the operation became successful.

Freeman’s Transorbital lobotomy turned a complex surgical procedure, which used to require an operating room and a neurosurgeon, into an outpatient procedure. Soon, hospitals across America started to treat patients with lobotomy. Doctors, the press, and the public enthusiastically embraced the procedure. In this article, we tracked the early interest in lobotomy. It is key to note that lobotomy was one of several shock therapies introduced during these years, in an effort to: a) treat patients who appeared incurable; b) make difficult patients manageable, and c) reduce the number of institutionalized people because hospitals were overcrowded.

The rapid diffusion of lobotomy quickly increased awareness about possible side effects. The press and many doctors eagerly advocated for lobotomy’s alleged therapeutic benefits despite knowledge that lobotomies could dampen creativity, leave some patients in a vegetative state, or have little to no benefit. Freeman recognized the operation could have side effects but emphasized that lobotomized patients could work and return home. He reported that a third of his patients were cured, another third improved, and the final third remained the same. Unexpectedly, lobotomy proponents became convinced that a wider set of mental problems could be cured through lobotomy. In this post, we explored this enthusiasm, which included efforts to eliminate criminal tendencies, and correct children’s misbehavior through lobotomy.

The introduction of the so-called chemical lobotomy, coincided with growing concern about how the psychiatrist’s arsenal could be used to reshape individuals. Thus, an operation that was once widely adopted, suddenly lost its popularity. Old criticisms were highlighted and revived.

In less than one hundred years, lobotomy has lived many lives. The first one was its invention, initial application, and expansion. Then, it took another life as the operation was prescribed to treat a wider range of ailments and awareness about its side effects grew. A third life was characterized by its decline and demonization. Lobotomy’s fourth life is one where the public forgot that it was ever respected, and professionals thought it would solve social ills. Lobotomy continues to live through film and literature. We are working on analyzing how lobotomy was depicted through time, and we share some of the films which feature lobotomies below.

At times, the public has followed the development of psychosurgery with fervor. We have identified over fifty films in which lobotomy or psychosurgery is a significant part of the plot. These films are all little windows into how society understood lobotomy’s potential and its problems.

Man in the Dark (1953): This film was one of the first to use 3D technology and features a criminal who was released after a lobotomy cured them of their criminal tendencies.

Suddenly, Last Summer (1959): Based on Tennessee Williams play, it tells the story of a young woman forced by a vengeful aunt into a lobotomy to hide an uncomfortable truth. It also shows a more humane and conscious approach to psychosurgery.

A Fine Madness (1966): A scathing critique of mental health systems. The film follows a failed poet and satirizes the state of American societies and psychiatric institutions.

A Clockwork Orange (1972): An iconic film about a dystopian future in which the State deploys a medical intervention (which makes criminals feel disgust about the crimes they committed) that turns criminals into allegedly good men.

One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975): A classic film which is an indictment of psychiatry. It posited that rather than curing patients, mental health professionals use shock treatments to maim and subjugate them.

Session 9 (2001): A psychological horror in which a crew of asbestos removing workers is sent to work on an abandoned asylum with a dark past. It symbolizes the danger of mental illness and the potential harm caused by treatment.

Shutter Island (2010): A thriller in which a patient received an extreme form of therapy in an effort to cure them.

Superman Red Son (2020): a unique take on the superhero classic. Superman is raised in the USSR and becomes a beacon for Communism. However, to build his utopia, he has to resort to mind control technology, and other tactics.

We think that one lesson we can draw from lobotomy’s many lives is that social problems are complex and simple solutions, however alluring, are unlikely to fully solve them. Secondly, while science, medicine, and technology are likely the best way to learn about the world, they are far from perfect and we should be cautious rather than zealous in implementing solutions which can harm our fellow travellers.