Cutting Through The Problem: Early Enthusiasm for Lobotomy

The Press Enthusiastically Endorsed Lobotomy 1935-1944

Today, it may be hard to believe that lobotomy, the separation of the frontal lobe from the rest of the brain, was once seen as a legitimate medical procedure. Yet, thousands of lobotomies were performed, and even some lobotomized patients improved. From today’s vantage point, this operation is associated with the “most barbaric and arrogant face of psychiatry’s ignorance,” nonetheless as we shall see, it was once part of the medical arsenal (Harrington, 2019, p.57). Seeing lobotomies simply as an aberration misconstrues the past and fails to provide useful lessons to neurologists, psychiatrists, and the public. In 1985 some psychosurgery was still being performed but at a much smaller scale (Kleining, 1985) . The Press, and especially a newspaper of record like the New York Times, is a useful way to study public perception and discourse throughout time.

The New York Times’ coverage of shock treatments is overwhelmingly positive. The Times published sixty five articles about lobotomy between 1935 and 1964. Analyzing these suggests three eras which we will explore in three articles. These are: enthusiastic endorsement (1935-44), lobotomy in practice (1945-1954) in which articles start to mention side effects, and the eclipse of lobotomy (1955-64). These periods coincide with the development of heroic treatments, the increased use of shock therapy, and the development of drugs like thorazine respectively. During their heyday, lobotomies would also be used to try to literally cut criminal impulses out of people’s brains.

We have looked at every article published in the Times, during these time periods which mentioned shock treatments. We were inspired by some researchers who analyzed qualitatively and quantitatively the content of popular press articles between 1935 and 1960 (Diefenbach et al). They found an initial period of uncritical reporting which progressively became more critical of lobotomy. We also looked at articles between 1960 and 1964 and expand of Diefenbach’s analysis.

During the rise in lobotomy’s popularity some of the press starts to mention side effects, yet these are mostly presented in a positive light (Diefenbach, et al 1999). We also found that during the lobotomy in practice period, articles included an expansion of the therapeutic range of lobotomy. That is, they suggested that lobotomy could be effective at treating an expanding a number of conditions. Thus, we concluded that while articles do in fact start to discuss side effects, they are at the same time more enthusiastic about the possible uses of lobotomy.

Background

At the dawn of the 20th century neurologists were critical of mental asylums which had become overcrowded. The World Wars worsened this problem by flooding such institutions with war torn patients. These were miserable places. Doctors, patients and their relatives, politicians and many others were frustrated and eager for a quick fix (Kleining, 1985) . One of the biggest challenges were schizophrenics who comprised about half the patients and were deemed unlikely to be cured (Presman). During this time there was also a “polarizing conflict between the proponents of biological psychiatry and the advocates of talk therapy” (Waller, 2014). However, the problem was of such magnitude that even the most ardent supporters of psychoanalysis “ruefully admitted that it could not handle mental patient in the mass”(Pressman) . For most of the next few decades, many psychologist and advocates for the talk cure would argue that medical interventions could assist with psychotherapy (Lanzoni).

During the early twentieth century psychiatrists and neurologists noticed, that on occasion, patients improved after suffering some kind of shock (Harrington, 2019). Therefore, they sought to recreate these conditions in the hope of curing their patients. Thus, they adopted “somatic, risky and often drastic interventions for psychiatric patients” which were seen as “acceptable by both physicians and the lay public” (Raz, 2013). The five shock treatments were: electroconvulsive shock therapy, malaria, insulin shock, metrazol, and psychosurgery (Harrington). Between 1935 and 1941 some seventy-five thousand patients would be administered some kind of shock (Pressman).At the same time, other doctors and politicians who were concerned about the quality of the human stock had advocated the sterilization of those deemed biologically unworthy (Harrington).

The Emergence of Lobotomy 1935-44.

Psychosurgery gained popularity in a community and culture that was looking for technological solutions to societal problems. This operation offered a solution to many of the problems psychiatrists and neurologists faced: patients were easier to deal with, they could often be discharged (making room in overcrowded wards), and it offered a cure for mental diseases (Raz). Egas Moniz performed the first lobotomy in 1935 (Valenstein, 1977). It is said that he was inspired by the work of Yale researcher Fulton. Fulton described an experiment in which Becky, a chimpanzee, became more docile after her prefrontal lobes were separated from the rest of her brain. Moniz tried the operation on a human and claimed some success. Thirty five thousand more lobotomies would be done by 1970 (Kleining, 1985, p.7).

Walter Freeman, who brought the procedure to the United States, originally suggested that they only be used in the case of schizophrenics (Harrington). Lobotomies emerged, at first, as a last resort for people with extreme levels of “anxiety and obsessive thoughts” (Harrington). Some accounts have claimed that Freeman and a “handful of zealots” were responsible for the adoption of this procedure. He has been described as a “zealous crusader”, a “flamboyant zealot” whose “confidence knew no bounds”(Kleining). While Freeman did do everything he could to “stimulate interest,” lobotomies gained popularity because professional neurologists, psychiatrists, asylums, and people were seeking that kind of solution(Pressman). Thus psychosurgery became the “single most important treatment in cases of severe mental illness” (Pressman, 1986, p.10). Lobotomy was adopted by about forty-one percent of the inpatient facilities and such widespread adoption cannot be explained as the work of a few zealots(Pressman). Lobotomies were popular and both doctors and the press were enthusiastic about its potential to help thousands of patients overcome several mental illnesses.

The Times Enthusiastically Endorsed Lobotomy

The press enthusiastically welcomed Walter Freeman’s introduction of lobotomy to the United States. On the front page, Laurence, a reporter, wrote that a lobotomy “transforms wild animals into gentle creatures” (Laurence, 1937). He claimed this operation had a 65% success rate. Laurence wrote about a woman who prior to being lobotomized was confined to her home, and was not managing her household, enjoying seeing people, and even driving her own car(Laurence, 1937). The editors placed this article on the front page approving language and tone which suggested this operation was promising.

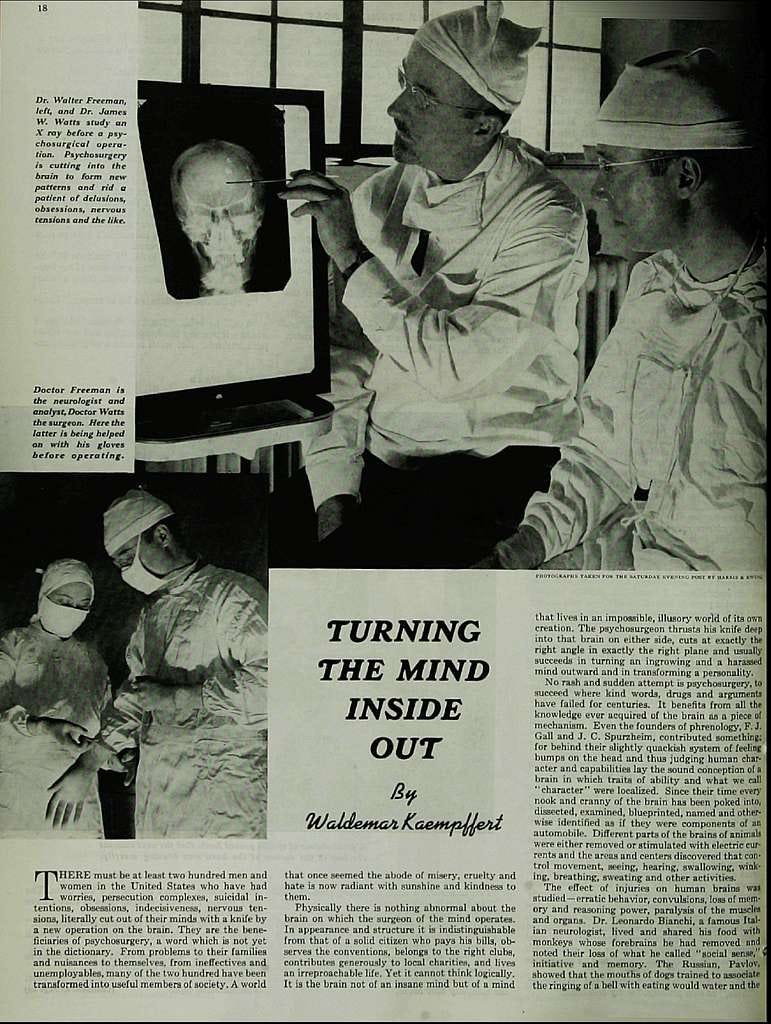

The press remained enthusiastic about lobotomy. From the very first article by prominent science journalist Waldermar Kaempffert, wrote that patients who were “ineffective and unemployable” went from being “problems to their families and nuisances to themselves”, to “useful members of society” the press was largely uncritical (Harrington). Reporters celebrated “scores of success.” “melancholics became cheerful. Worry, fear and hate disappeared. The world which had appeared so dark, became a delightful place”(Kaempffert, 1937). The language exudes hope, optimism and helps portray this procedure as a game changer. Another article discussed a publication in JAMA which spoke about two hundred successful cases in which “depression, suicidal tendencies, persecution mania, and intense worry” had been turned into “something like social sanity” (NYT. 5) Lobotomies allegedly transformed people, so other enthusiastic reporters tried explaining why the operation worked. They suggested the brain was composed of two parts which are in tension. The deeper, more ancient brain called thalamus and the frontal lobes. Laurence made similar claims and connected mental disease to dysfunctional frontal lobes (Laurence, 1937). Despite some concerns about the operation it gained support. Lobotomy’s promises helped make psychiatry a “successful medical speciality” (Pressman).

The Times, like lobotomy’s most ardent advocates, focused on the therapeutic potential rather than on the side effects of lobotomy. Pressman, a historian, has argued that even before Moniz performed his first lobotomy there were medical case studies which cataloged the deficits that these kinds of injuries had on soldiers. It appears that Moniz was not bothered by any deficits that may be associated with prefrontal lobe lesions (Kleining). Likewise, Freeman sustained that the operation made patients into “rather good citizens” even if they were less creative (Kleining). Lobotomy worked because it eliminated the very symptoms that had pushed these patients away from society even if it stifled the “creative and stimulating contribution to social life” that patients could make(Kleining).

Lobotomy and Rejoining Society

Lobotomy was seen as useful because patients could often return to society and if they could not, they were left “well-adapted to institutional life” (Pressman). The press mostly agreed with Freeman who did not care “if a patient is no longer able to paint pictures, write poetry, or compose music, he is, on the other hand, no longer ashamed to fetch and carry, to wait on table or make beds or empty cans” (Pressman). Despite some knowledge about possible side effects, news articles overwhelmingly supported lobotomies.

Often these unplanned changes in patient personalities were given a positive spin. During this period, articles which mentioned changes in personality tend to extol these changes as beneficial. For example, Laurence, described “the change in behavior which persists is slight and may be described as emotional, flattening, diminished spontaneity, lack of attention and indifference”(Laurence, 1937). The use of slight is important as is the flattening given that most of those being lobotomized would have been said to be overly emotional. The press also recognized that some people died while being lobotomized; however, this intervention’s record was “as good as in most major operations” (Kaempffert, 1942). When Freeman introduced the prefrontal method, the mortality rate was dramatically decreased and hence there were even fewer concerns.

We have reviewed all articles in this time period which mention lobotomy and most portray the use of lobotomy in a positive light. While it is difficult to ascertain whether lobotomy became popular as a result of positive press or that it got positive press as a result of its popularity, the fact is that institutions like the Veterans Administration, in 1943, was encouraging their staff to obtain “special training in prefrontal lobotomy”(Valenstein, 1977).

The Times published more articles on lobotomy than any other shock treatment during this period. Their coverage of lobotomy was more positive than their coverage of other shock therapies. We have reviewed every mention of lobotomy, electro shock, metrazol in the New York Times up to 1954. Lobotomies had the most articles and out of these the highest number of positive ones. The Times published thirty-two articles which mentioned lobotomy and twenty one of those were positive about its therapeutic value. Only two articles were negative. In contrast only five articles were published about metrazol and four of these were positive. Fifteen articles mentioned electroconvulsive shock, seven of which are positive about its value and five which criticize it. In general these articles are positive about the therapeutic promise of shock treatments.

Criticizing Lobotomy

Despite there being disagreements about the possible therapeutic value of shock therapies, criticisms of lobotomy were not commonly published. An esteemed health professional, Bernard Wortis, was horrified when he learned about lobotomies and he feared an “epidemic of progressively eviscerating patients” (Harrington, p.68). The famed Adolf Meyer supported cautious experimentation (Harrington). There were a few others voices that expressed concern like AA Brill who, in 1938, opposed the use of lobotomy as it was “too experimental”(Diefenbach). Three years later, at the American Medical Society Meeting, some physicians would express concerns, largely ignored by the press, about possible side effects that lobotomies could have (Diefenbach). In some instances reporters sought opinions and gave more credence to positive ones.

Freeman invited Kaempffert to witness a lobotomy and report on it. Kaempffert wrote an article for the Saturday Evening Post. Kaempffert was impressed and called the New York Academy of Medicine which expressed “bitter opposition” to administering lobotomies (Pressman). Undeterred, Kaempffert reached out to Fulton who expressed enthusiasm about lobotomy’s potential and provided sources for the journalist(Pressman). At the time many articles made references to Fulton’s work and research (Pressman). He was well respected. His laboratory was at Yale and he was the person seriously researching the brains of other apes. Thus, his opinion carried weight. The press, like many mental health professionals, were brimming with enthusiasm and hope as the plight of those with severe or chronic conditions was finally within the reach of science.

Conclusions

To a contemporary audience lobotomy appears barbaric, yet however baffling it may be to us, it was widely practiced and widely popular. During the first decade after its introduction thousands of patients were lobotomized and many hospitals prescribed lobotomies as treatment. Walter Freeman, who introduced lobotomy into the US, was well-respected and prestigious. Between 1935 and 1944 the press was enthusiastic about lobotomies even when they mentioned side effects. None of this appears malevolent. In short, society can be overzealous when embracing technological, scientific, and/or medical solutions to social problems.