Mad Doctors, Ice Picks, & Lobotomized Children: The Lessons Behind Dully’s Tragedy

“My stepmother arranged it. My father agreed to it”. Dully was only twelve when he was lobotomized. How can we prevent such tragedies?

Howard Dully was lobotomized when he was twelve, which left him with a “badly damaged brain” (p. 280). Dully’s tender age saved him from becoming a vegetable because he was young and his brain was still developing. Dully wrote a memoir called My Lobotomy with the help of Charles Fleming. The result is gripping and tells the incredibly sad and moving story of a child who had abusive and negligent parents who got him lobotomized. My lobotomy gives readers a window into Dully’s experiences and a time, not so long ago, when a physician could lobotomize a child. Dully implied that Walter Freeman, the doctor who popularized lobotomy and who operated on him, was a charlatan who zealously pursued fame. The memoir is also an indictment of past and present medical practices. Despite the book being engaging, authentic, and moving, the memoir draws problematic lessons from Dully’s lived experiences. Consequently, readers could wrongly conclude that preventing abuse of individuals is easy by a society wary of overzealous, charismatic professionals who peddle new cures. However it is not as easy to tell wrong from right.

Dully, at the time of publication (2007), worked as a bus driver. The memoir can be divided into four parts: childhood, lobotomy, consequences, and acceptance. The first part is about Dully’s childhood. Dully had a close relationship with his mother, who died when he was four (p. 2). His father married Lou, who is portrayed as being a terrible mother-in-law (chapter 2). She was abusive and even spanked Dully when he took food without permission (p. 24). Dully wrote that he “wanted to love her, and I wanted her to love me” (p.148). Dully recounts some childhood shenanigans but nothing out of the ordinary. However, Lou was convinced that Dully’s misbehavior was something that needed to be cured. She took him to several doctors, who all concluded Dully was normal (p. 58–60). Finally, she found someone who would listen: Dr. Walter Freeman.

The book briefly describes Dr. Freeman, the father of American lobotomy, detailing the events that led to Dully’s lobotomy. After the operation, Dully recounts bouncing from different institutions, abusing substances, and other problems. Finally, the last few chapters explore how Dully got his life back together and how the book originated. In My Lobotomy, Freeman is, understandably, portrayed as a reckless quack despite some attempts to contextualize his work. Dully critcises Freeman’s practise, theories, and actions. However, Dully’s critiques are anachronistic; that is, they measure the past through today’s standards. Examining Freeman is key to determining how an intervention like the lobotomy gained popularity and how to prevent such potentially destructive treatments in the future.

Dully claimed that Freeman “wasn’t very successful” as a doctor (p. 63). Nevertheless, a young Walter Freeman was seen as a “successful young clinician” (Raz, p. 6). He achieved plenty early in his career and was quickly promoted. Freeman was a founding member of the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology. He presided over the Philadelphia Neurological Society (1945) and the American Association of Neuropathology (Raz, p. 6). All these achievements happened while lobotomies were accepted, which shows that he was a well-respected member of the medical establishment. Although it may shock readers today, lobotomies were considered a valid therapeutic tool and practiced in hospitals all over the country (Raz, p. 2). Many professionals thought that mental illness had a physiological basis and thus demanded physical interventions. Egas Moniz, who invented the procedure, was honored with a Nobel Prize in 1949 (Harrington, p. 70–71). It is especially important to recognize Freeman’s professional standing to draw useful conclusions from this period.

Secondly, Dully argued that Freeman was reckless. Dully uses his lobotomy to substantiate his case. For example, reflecting on how Freeman chose to lobotomize him: It took less than two months, four visits with Lou, and four with Dully to “convince Dr. Freeman that a transorbital lobotomy was the only answer to our family’s problems” (p. 91). The way in which Dully described the procedure disparaged Freeman. Dully wrote that Freeman “poked these knitting needles into my skull, through my eye sockets, and then swirled them around until he felt he had scrambled things up enough. Then he took a picture of me with the needles in’’ (p. 97). Many decades after his lobotomy, Dully found that Lou had invented a story to convince Freeman to operate. Lou claimed Dully had beaten his baby brother. Dully was angry about “how easily the decision was made” (p. 91). Freeman’s detailed records reveal that he suspected Dully was a schizophrenic. The fact Lou had to make up an extreme story suggests that Freeman had, at least, some restraint. The decision to lobotomize Dully seems, from our vantage points, crass and horrid. However, Freeman met with at least five people and Dully to reach a diagnosis. He saw Dully four times and concluded that he “was unapproachable by psychotherapy”, (p. 91). At the time, lobotomies were commonly used for adult schizophrenics. Readers are not given enough context to determine whether this was insufficient consultation. How long did the diagnosis of schizophrenia demand? Dully was able to tell this story because Freeman diligently kept notes on all of his patients.

Freeman maintained extensive and detailed records that suggest ethical and appropriate practice (Raz, p. 23). During the 1950s Freeman went on trips as part of Operation Icepick. During these trips, he would teach other doctors his procedure, lobotomize patients, and visit former patients (Raz, p.23). Freeman interviewed patients, and their relatives, and corresponded with their physicians before deciding whether to lobotomize them (Raz, p. 23). He obsessively corresponded with his patients and their families, many of whom were effusively thankful and appreciative (Raz, p. 82–92). Some of these returned for a second lobotomy or referred other patients (Raz, p. 70). In short, for the time in which he practiced, he appears to have been diligent in both determining who needed surgery and in studying whether they improved.

Dully concludes that performing a

“transorbital lobotomy on a twelve years old boy was wrong. To perform it on a boy like me, who doesn’t even qualify by Freemen’s published standards for the operation, was particularly wrong. But it would have been barbaric to do to any child.” (p. 269).

While we agree that lobotomizing any child is barbaric, this too, needs to be contextualized. Freeman, like many promising young American doctors, had trained in France. His experience at Salpetriere taught him that he could learn by treating patients. Secondly, he grew frustrated and decided to be different, “doctors he thought had to at least try” to help (Raz, p. 23). While Dully is correct that when Freeman first proposed lobotomies, he opposed their use for schizophrenia; he omitted that Freeman changed his mind after developing the transorbital approach (Harrington, p. 72).

Dully claims that Freeman misrepresented the success of lobotomy. Dully argued that surgeries were portrayed as successful because the “worse symptoms had disappeared” (p. 66) despite other negative side effects. Moreover, he accused Freeman of trying to hide the stories of many patients who were “damaged by the surgery” and who “needed to be taught how to eat and use the bathroom again (p. 67). We know, however, that Freeman kept detailed records of patients who died and those who did not improve. More importantly, the criteria for what constitutes success should be explored. It is imperative to remember that lobotomy was one of four shock treatments that were deployed to deal with an excess of patients who appeared to be incurable. Further, the same procedure with the same outcome can be interpreted differently by historical actors in a different space and time. To illustrate this point, the lack of emotional range which is now perceived as a result of the damage inflicted by lobotomies, was welcomed by many of the families of those who were lobotomized (Raz. p. 72–74). Freeman simply did not care if his patients lost their ability to “maintain complex positions” (Raz, p. 131). Freeman assessed his success by determining whether patients could “return to a useful life” (as cited in Raz, p. 20). We do not think these criteria are acceptable; we merely want to stress that the criteria by which success is determined changes.

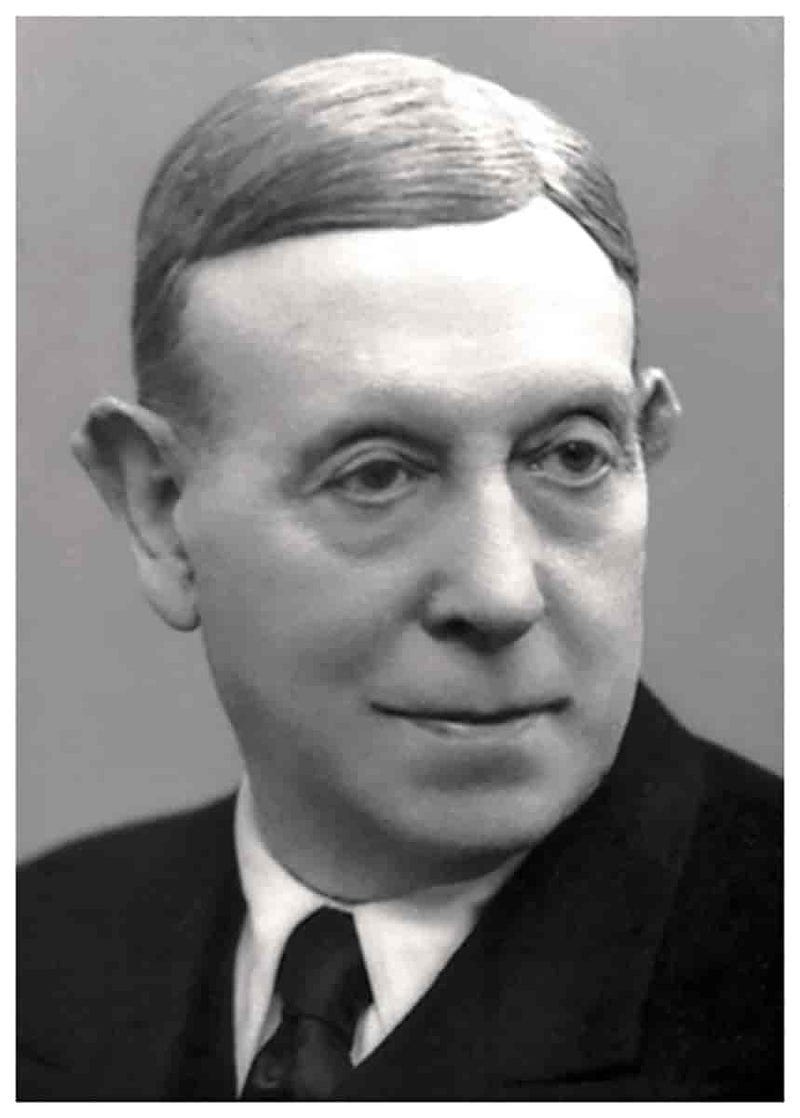

Dully wrote that Freeman “did not have much patience for standard medical practice” (p. 73) and that he began operating in his office. This portrays the development of trans-orbital lobotomies as dangerous and reckless. James Watts, who had been the surgeon who operated on Freeman’s patients, broke off their relationship when Freeman started using the orbital approach in his office. Watts deemed that lobotomies were serious procedures that needed to be done in an operating room. Freeman used to take photos before, during, and after surgery (see the photo of Dully at the beginning of the article). Dully discussed Freeman’s last surgery to reiterate the image of reckless doctor. Freeman, “made his last mistake” when he was seventy-two and his patient died during surgery (p. 189). Dully rightly presents this as irresponsible. In fact, Freeman killed a patient because he stopped to take a photo during a lobotomy. While this is inexcusable, it only affected very few patients. Throughout this discussion, Freeman is portrayed as reckless and more interested in promoting himself than in developing a cure. Whereas one could interpret this shift as a way to ensure that patients could promptly return to their lives, which was one of the ways in which Freeman assessed whether the lobotomies work (Raz, p. 120–121). Freeman did endanger his patients when he attempted to take photos while leaving the surgical equipment inside the patients. The fact Freeman was able to do this is outrageous.

A third criticism is that Freeman was more interested in fame than developing effective treatments. Dully wrote that for Freeman, “performing the lobotomy ‘’ was more important “than treating a patient” (p. 267). Freeman did make an effort to popularize lobotomy. He invited journalists to witness the procedure. He traveled often to promote the use of the operation and to teach others how to perform it. For Dully, not only did Freeman lobotomize without good reason; he operated irresponsibly.

Historians tend to attribute the success of lobotomies to a series of issues like the lack of effective treatment of mental disorders and the excess of patients after WWII. Desperate to help, doctors tried several “somatic, risky and often drastic interventions for psychiatric patients” which were “seen as acceptable by both physicians and the lay public” (Raz, p. 1). When lobotomies are first proposed there are some early critics. When Freeman initially introduced his project on lobotomy at a college, Dr. Bernard Wortis, a leading psychiatrist and neurologist who eventually became chairman of psychiatry at NYU, was horrified and warned about an “epidemic of progressively eviscerating patients” (Harrington, p. 68). Likewise there is a report in 1948 that was highly uncharitable of Freeman. This report was more concerned with the selection criteria and evaluation than of the theory that severing the connections inside a brain could cure mental illness (Raz, p. 46). Moreover, when Dr Freeman took Dully and other children to showcase at a conference at the Langley Pleter Clinic, Dully told us doctors were outraged and that they screamed “only twelve? It was outrageous”. (p. 102). Freeman’s was invited to speak and he was allowed to bring these children onto the stage. Moreover he thought the talk would be well received. These two facts suggest that lobotomizing children would at least be plausible for some portion of the crowd.

Dully was a child when he was lobotomized, thus his experience is not a good archetype to understand neither most patients’ experiences nor medical cases in which this operation was used. Most patients who received lobotomies were adults. The majority had been diagnosed as schizophrenics and were deemed as beyond the reach of other therapies. Dully’s case is a tragedy. However, by focusing on one of the most extreme examples and not contextualizing how lobotomies gained popularity; Dully makes medical practice appear reckless rather than the product of historical actors who eagerly sought a way to help their patients.

My Lobotomy is a useful introduction for the public into a practice that is nowadays rightly recognised as brutal. It serves as a useful warning to medical professionals who need to be careful that they are not causing more harm than good in their zeal to cure disease. It can open a discussion into how medical professionals, patients, and their families evaluate the outcomes of medical interventions. It is informative on the effects that diagnosis may have on identity. Dully made wrong choices, in part, because he thought he deserved his lobotomy. Dully’s greatest misfortunate appears to have had horrid parents who existed in a world where children could be lobotomized.

Given what happened to Dully, his portrayal of Freeman is quite fair. Nonetheless, Dully undermines his most important lesson by portraying Freeman as part of a set of practitioners administering treatments that would appear to be “plain crazy now” (p. 64). Well-intentioned scientists, doctors, government authorities, or even parents, can be seduced by novel treatments and promises which end up harming those they intended to help.

Authors: Christian Orlic. Christian wrote a book review on this memoir for a History of Science class. This work draws heavily from that essay. Lucas Heili provided valuable commentary and feedback.

Christian admires Howard Dully's bravery in coming forward and telling his story. I am deeply sorry that this happened to him and other children. I hope that drawing some complex lessons can help avoid such tragedies.

Sources:

*** Quotations in brackets with no author name come from Dully & Fleming.

Dully, H., Flemming, C. 2007. My Lobotomy: A Memoir. Three Rivers Press. New York.

Harrington, A. 2019. Mind Fixers: Psychiatry’s Troubled Search for the Biology of Mental Illness. W.W. Norton & Company. New York / London.

Raz, M. 2013. The Lobotomy Letters: The Making of American Psychosurgery. University of Rochester Press.

Originally published in Medium

I appreciate the effort to contextualize the practice of lobotomy back in the day. On the other hand, I think the understanding of the brain (then or now) was so poor that it really was quite reckless.

"We don't know why it works sometimes and fails others but I'm going to do it anyway," is very unscientific.

This is a really interesting read. Thanks for posting it! I'll cross-post to my own Crime & Psychology Substack because I'm sure my subscribers will enjoy it, too.