MAGA: Make Argentina Great Again

Argentina's complicated embrace of Science, Medicine and Technology to solve social issues.

Argentina’s current president, Javier Milei, has often reflected on the nation’s past, especially the late 19th and early 20th-century, as the golden years of the country brimming with progress and prosperity. He has emphatically expressed his desire to bring back the country to this era of development, to Make Argentina Great Again if we borrow from current political lingo. Whether he manages to do anything of the sort, is to be seen, but in this post we will explore the nuances and realities of this period of Argentina’s history.

By the late 19th-century, Argentinian elites prided themselves in being among the leading economies in the world. They championed classic liberalism, scientific progress, and innovation as the forebringers of economic development. Accompanied by the United States, the Argentines saw themselves as harbingers of progress and civilization in the American continent. The country’s capital, Buenos Aires, was often compared to Paris for its beauty and cosmopolitan ambiance.

To this day, much of the Argentinian public opinion refers to this golden era with an air of nostalgic pride, hinting that something was lost along the way which led to the country’s tragic present. A deeper exploration of Argentine history reveals that much like in the United States, science and medicine provided justifications for policies that today would be condemned, in part because of their discriminatory nature.

History is never as pretty as popular nostalgia suggests. This rosy view of Argentine history is called into question in Julia Rodriguez’s book, “Civilizing Argentina,” published in 20061. She argues that Argentinian elites, while claiming to be liberal and cosmopolitan, utilized the apparatus of the state to enforce elitist policies in the name of science, civility, and economic expansion. In her book, she situated current challenges in Argentina, within the framework of early 20th-century Argentinains understanding of poverty, gender discrimination, unemployment, alcoholism, and crime as illnesses (Acuña, 2007).

Establishing A Hierarchy of Race

The “golden generation of 1880” sought to emulate the alleged success of their North American counterparts, and like them, thought that some immigrants were better than others. These Argentinians were convinced that immigrants from Northern European and protestant countries were preferable to those coming from Southern Europe. Ironically, the overwhelming majority of immigrants arriving to Argentina came from Italy and Spain.

These Argentinian thinkers viewed the Native American peoples which inhabited the southernmost region of the continent as barbarians. They considered their culture and behavior to be opposed to progress and development, and considered them as an inferior race. Their efforts were focused at eliminating the natives, cowboys, and caudillos to gain access to their land and resources. Furthermore, they sought to eradicate what they considered to be a social pathology, their “savageness”, because they thought it would hinder the country’s development and international position. As a result, they successfully led multiple military incursions into their territory to push them back and eliminate them.

To justify these efforts, “physicians and scientists were tapped by the government to diagnose, prescribe, and cure perceived threats to national progress.” As we have seen in previous posts, state actors often make use of the authority provided by other institutions, such as doctors and scientists to justify their fears and anxieties. Well-respected physicians, such as Lucas Ayarragaray who studied the “psychological origin” of Argentina as a nation, declared it to be violent, decadent, and indolent as a result of intermixing with the rural population (Indians, gauchos, and caudillos). He worried about the influence of a depressed and stagnant culture for which the Spanish were famed for.

Later that year, José Ingenieros, one of the most prominent psychiatrists in Argentina’s history, criticised Ayarragaray’s publication for ignoring the racial factors that, in his view, accounted for these pathologies. Other prominent scientific and medical professionals supported similar rationales to both Ingenieros and Ayarragaray, providing state legislators the necessary authority to enforce policies aimed at social control, “segregation, confinement, or deportation for persons regarded as beyond cure.”

Nonetheless, prominent intellectuals such as doctor and politician José María Ramos Mejía argued that the racial differences, namely the biological inferiority of certain types of immigrants, could be overcome through a process of social integration. Thus, by enforcing civilization into the ones deemed undesirable, they could correct these pathologies and bring all these people up to a similar level as the better ones. We see that while many of these intellectuals shared ideas, frameworks, and heuristics they also had disagreements.

At the time, there was a widespread belief that criminals could be identified for their unique traits and tendencies, thus making it possible to classify them and discriminate them through scientific study. This would be an important part of any burgeoning nation’s policy so they could allegedly build a better society.

Understanding Crime as Disease

Progress and civilization brought a new vision of criminals and criminality. Scientists and criminologists began to see crime as a consequence of modernity, to be treated in the same way as one does a disease. The Argentinian government seized the opportunity to support their hygienic policies with scientific arguments. A series of social standards were set, and those who deviated from them were seen as symptoms of sickness. Madness, alcoholism, vagrancy, suicide and prostitution were among the top concerns for the state and their scientific cohorts. For example, these men labelled prostitutes and suffragists both as social parasites because they threatened to upend their perceived ordered society (Acuña, 2007).

The effort to cure such maladies led to the profound study of the prison population. Since its inception, the Argentine nation seeked to remove dangerous individuals from the street, causing prisons to gain relevance in civil society. In the early 20th-century, medical professionals sought to understand and consequently deal with the “sick” individuals inhabiting prisons. This methodology further reinforced their theories of biological quality and inherent criminality of a subset of the population.

As a solution, in 1877 lawyer Fermín Alsina argued for turning prisons into work and education centers. Alsina believed work to be an ideal form of therapy for the dignified man, and would turn them away from their criminal impulses. He also championed the role of education in societies, as the main driver for a better and more prosperous society. It is interesting to see how these views emphasise both biology and sociology. However, these were not the only solutions presented. Other members of the legal community saw prisons as a shield against the dangers brought by massive immigration. Threats of anarchist crime, white slave trade and others were linked to arriving populations.

For that group, segregation served as the tool for isolating these evils. Special institutions were developed to deal with these maladies and avoid contamination, suggesting that they interpreted these issues as both biological and environmental. Whether alcoholics, anarchists or prostitutes, all were treated separately. The progressive view, the understanding of crime as a disease, and the intention to reintegrate “degenerates” into society, poses prisons as “social hospitals” rather than merely a place to lock problematic individuals away.

Leveraging Technology for Social Control

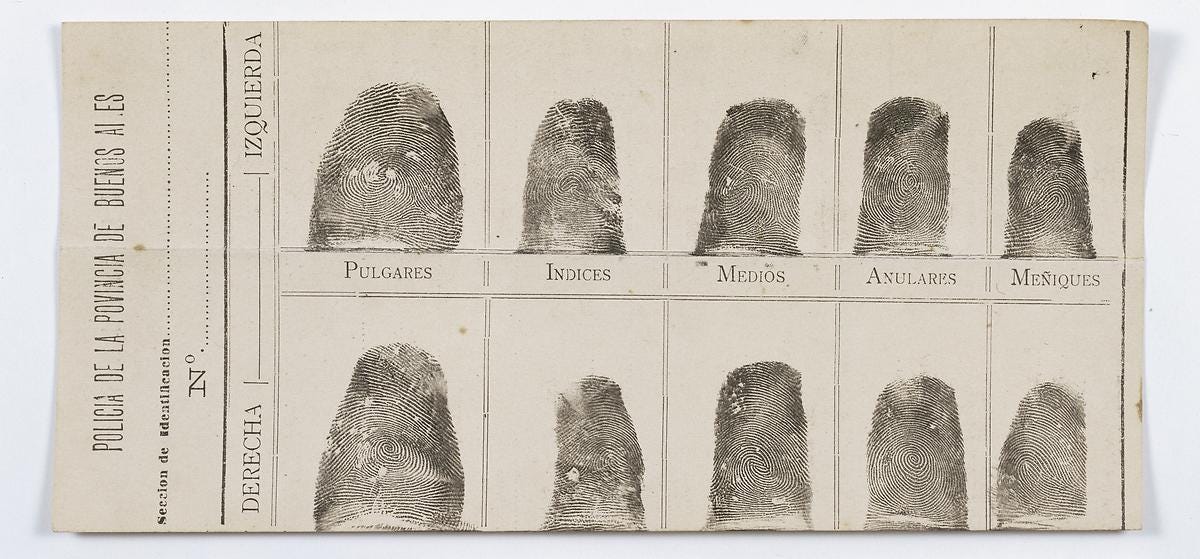

Technological advancements helped the government with their process of controlling and segregating the population. Yugoslavian born statistician, Juan Vucetich, was one of the first ones to apply his scientific methods of classification for the apparatus of the state. Working for the police, Vucetich pioneered the science of dactyloscopy: analyzing fingerprints to identify individuals. His work gained great notoriety among criminologists, police and scientists around the world, and served as a tool for identification and classification of individuals by the state. This was an improvement over Bertillion’s identification methods. Dr Dr Angela Buckley discussed Bertillon's innovations and Dr. Jason Frowley PhD described his doomed efforts to measure criminals.

We will explore Vucetich’s technology further in future posts. Rodriguez reviewed the personal archives of Vucetich and also mentioned he thought he had found fingerprint patterns that correlated with a predisposition to criminality. @Jasonfrowley has discussed that criminologists have often claimed that inner tendencies to commit crimes have physical manifestations.

Conclusion

The famed “golden era of Argentina” must be taken in with caution. There was, undoubtedly, a measure of economic success, development, and social homogenization. However, as Dr. Julia Rodríguez points out, this progress came with a series of anxieties and concerns. While claiming to bring civilization and enlightenment, the Argentine elites employed the apparatus of the state, and the authority provided by science, medicine and technology, to pursue their hygienic and eugenic agendas. She wrote, “the language of science and medicine proved useful to couch the state’s efforts to maintain control. Public health, criminology, criminalistics, and penology more than other disciplines served to mask larger meanings about social roles and expectations.”

The Argentinian elites instituted policies aimed at segregating, eradicating and deporting the types of people they deemed undesirable (indian, black, southern european, etc.). It is interesting to see contrasting and sometimes even contradicting views within their policies and agendas, yet they all seem to agree that science and medicine played an essential part in the pursuit of progress. This is another reminder and a lesson we often repeat: nuance is important in understanding the past. The fact these men disagreed over the degree to which biology mattered does not mean they were not operating under the same framework. We would expect to find such heterogeneity almost everywhere we look.

Rodriguez’s book is a stark reminder that there are dangers associated with the “liberal impulse to cure social illnesses. The result was not progress but decay, not a democratic but a totalitarian nation” (Acuña, 2007). While we consider Rodriguez’s view of this period to be a bit too critical, considering the context and historical period, - at the time, the Argentine elites were in fact following the most innovative and respected trends within these fields - we think science, medicine, and technology are incredibly powerful tools to understand social problems, as well as designing possible solutions, but these need to be carefully and thoroughly considered before being enacted.

Sources

Acuña, L.E. Book Review JHMAS. 2007.

This book is, at the time of this writing, almost two decades old. In this time, major political, social and economic changes have taken place in Argentina, which inevitably have an effect in our understanding of its content. While we are making a few connections to the present, such as Milei’s presidency, we must judge Rodriguez’s writing within its proper context.

This is such an interesting post, and thanks for the mention!