Communist Ideology Doomed Czech Work Camps

Communist Ideology Incongruent with Camps

In the 19th and 20th centuries, Nations have zealously tried to make healthy citizens out of troubled individuals. These efforts often involve segregating such individuals and forcing them to complete a specific program. Similarly, prisoners have instituted programs to reform criminals, and private businesses such as The Seed have offered to cure troubled teens. This post discusses the failure of work camps in Soviet Czechoslovakia.

The Collapse of Czechoslovakian Work Camps

Shortly after the Communists took power in Czechoslovakia, they established work camps in December 1948. Such camps were common in Soviet nations, and allegedly, they were meant to re-educate or reform enemies of the people. By 1952, Czechoslovakian camps had mostly disappeared.

According to Jiri Smlsal, most historians have focused on the persecution of political opponents, but have not explained why these camps disappeared so quickly.1 Smlsal proposes that the camps vanished because the Communist elite saw the camps as a “failed experiment.”

Making Good Communists and Work Camp Population

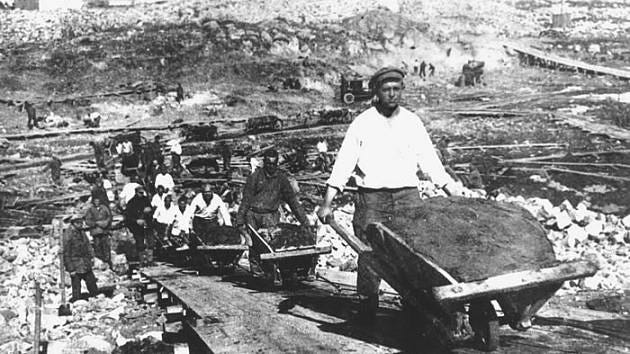

Czechoslovakian work camps were a response to an apparent crisis, and the goal was to incarcerate and reform the bourgeoisie, landlords, and those belonging to non-socialist political parties. The camps aimed to suppress opposition and instil “ a love of work” in these supposedly troubled people.

The Government installed a council of three people who would, without trial or process, decide whom to send to these camps and how long they would be there (months to years). While it may seem easy to dismiss the rehabilitative aspect of such camps, it is vital to remember how well these efforts fit within the broader communist paradigm, in which political opposition and social deviance were viewed not as irreconcilable flaws but as products of a wicked environment.2 In this worldview, men are products of their material relations, and such defects could thus be corrected through discipline, labour, and re-education.

Long-time subscribers may recall that we wrote extensively about Crime in Cold War Berlin and the manner in which ideology affected how Soviet Germany explained why people committed crimes.

The fact that individuals were committed to such camps for varying lengths of time reaffirms the purpose behind these camps, which was to transform them into good communists. Different individuals were deemed to require different lengths of treatment to correct them. The Czechoslovakian Head of the Camps Education Department claimed,

“Just as good parents vaccinate and treat their children –even when those children are uncomfortable —so too do we treat (and often with harsh surgery) people and groups of people who would otherwise be doomed…a whole lot of people from the camps will be returned to our national community as valid members.”

Interestingly, such discourse uses a medical metaphor to explain not only why the camps were necessary, but also to suggest that they would be effective. This shows how Soviet authorities viewed such reform and how they legitimised these interventions. Further, it demonstrates just how important the language of science and medicine became.

The Camps imposed physical labour as well as moral and vocational training on their subjects. Such training included literacy, which was meant to help them understand and utilise the new discourse. Those interned were asked to prepare presentations on current topics, which they had to analyse using the Communist framework. The effort to teach and have those in camps use such frameworks seems incompatible with the idea that camps were purely about forced labour. Forced labour was surely an important part, but it was also seen as a means to transform these individuals.

A Failed Experiment

Smlsal argues that the Camps failed because they were incommensurable with Soviet ideology. A mere year after the camps opened, the Chairman of the Camps was already dissatisfied with the presence of workers in these camps, as workers were not supposed to need such rehabilitative programs.

The Chairman of the Camps did not think workers belonged in such places. By November 1949, only 25% of the camp population were deemed to be class enemies. Most of those interned were “petty offenders, vagabonds, absentee workers, and prostitutes”, who were sequestered “alongside former politicians, entrepreneurs, and intellectuals.” The camps were explicitly designed to treat a particular group of people, who made up only about a quarter of the camp population. The resulting dissonance scandalised the elites because it was anathema to their understanding of the world.

Communist leaders blamed the special commissions that determined who was sent to camps, and endeavoured to remedy the situation. Despite these efforts, the proportion of class enemies did not increase, and by 1952, only 18% of those interned were categorised as class enemies. Prostitutes comprised about half the population of the camp.

The camps were meant to instil a love for labour, and yet most of those interned were already familiar with physical labour, which the ideology portrayed as a privilege. Within two years, the Camps were closed and merged with prisons. Some of those interned came to be seen as social parasites and received longer sentences.

Smlsal provocatively argued that the main issue behind the camp’s failure was that the working classes comprised a large proportion of the camp population and that this was incompatible with Communist ideology.3 He sustained that the correctional imagination was crucial to their delegitimisation, which ideologically explained both why these individuals were flawed and the kinds of interventions that would rehabilitate them.

Failed Camps Failed Hospitals

Smlsal sustains that the correctional imagination associated with communism eventually delegitimised Czechoslovakian work camps. The camps were an ambitious project to refashion people into good communists, and are not a story about lawlessness. Instead, about how the correctional imagination tied to an ideology can affect a nation’s aspirations and efforts to remake itself. After the collapse of this system, the Soviet government needed prisons instead of political hospitals. Further, this failed experiment reveals the inherent tension between rehabilitative and punitive approaches.

Conclusions

The case of the Czechoslovakian work camps exemplifies a recurrent theme throughout the 20th century: the zeal to shape people anew through social and environmental interventions. This program assumed that such a change is possible. Where does this belief spring from? How universal was it? To what degree were such interventions similar to what was happening in other nations? This program reveals a close connection between ideology and the implementation of such programs.

In the case of Czechoslovakia, it is interesting to see the system collapse because its implementation was incongruent with the ideological framework that supported it. This suggests that worldviews can be paradigmatic and that crises need to be resolved within ideological frameworks. In the West, too, there were efforts to transform individuals into better citizens, but as Di Castri has pointed out (2024), these have largely been forgotten.

This post substantially draws from a talk given by Lawrence. Last April 2024, I attended the ESSHC conference in Leiden. While I took notes on my iPad, the talks were short, and the pace was quite quick. Hence, I may have inadvertently made a mistake in transcribing or interpreting my notes.

In a series of articles about youth crime in Cold War Berlin, we explored how East Berlin specialists argued that Western influences caused crime and that capitalism caused anti-social behaviour.

Smlsal draws from Greg Eghigian's theoretical framework regarding the “correctional imagination,” which includes ideas, values, policies, practices, as well as subjects and objects, with public efforts to rehabilitate criminals.