Understanding The Troubled Teen Industry: Brainwashing and Behavior Modification

The Seed Inc., was among the first centers to allegedly treat Troubled Teens and bears some responsibility for spawning the troubled teen industry. While the origins of this industry have been linked to Synanon, its roots lay much much deeper. The Seed promised to turn wayward adults and teenagers into healthy, responsible, and desirable citizens through its challenging program.The program had a large number of supporters and detractors.

You can read our post about the Seed’s Program:

The Seed’s apparent success was recognized by the Broward County Personnel Association which “officially adopted” the program and made efforts to assist its operations (Hardy & Cull,1974).

In this week’s post, we explore the wider context that primed America to embrace the kinds of solutions that the Seed promised. The Seed operated in an environment that not only made its program appear legitimate and effective, but in which there were several powerful examples that made it seem that the full transformation of a person was not only possible, but actively being studied.

Designing Better People

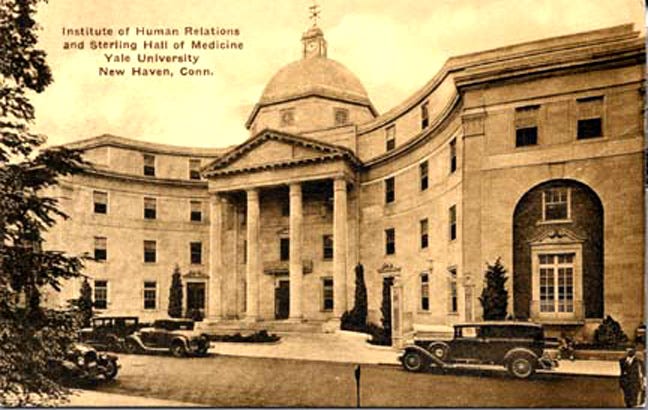

During the first sixty years of the 20th century, many psychologists and psychiatrists were enamored with the ideas of human engineering; these men believed that they could create better societies if they could only understand what drove individuals to behave improperly (Lemov, 2005). Their efforts gained wide support from governmental institutions and private philanthropy. Thus, these men embarked on a series of experiments and demonstrations that deeply impacted their fields and the world. These efforts should be distinguished from the eugenicists of the early 20th century, who sought to make better societies by encouraging certain people to breed and by sterilizing others. The enthusiasm for making better societies through breeding or environmental interventions was a common feature in the West. In 1939, the Rockefeller foundation gave millions (about half a billion in 2024 dollars) to a Yale professor to set up the Institute of Human Relations which would study behavior and seek solutions for juvenile crime, mental illness, and more (Lemov, 2005).

The National Institute for Mental Health was created in 1949 and its first Director, Robert H Felix, argued that psychiatry was becoming more focused on preventative measures because developing technologies could prevent problems from arising in potentially problematic individuals who could soon be identifiable (Lemov, 2005). During that time, psychodynamic psychology gained popularity and suggested that rather than focusing on individuals, actions needed to be taken at the level of the community or society (Grob, 1991). Likewise, a practice known as milieu therapy looked at the person’s environment as a means of curing them. Under Felix’s stewardship, the NIMH supported multidisciplinary approaches to mental health (Grob, 1991). Professional psychologists and psychiatrists embarked on an exploration of behavioral modification.

The prospect of transforming criminals, delinquents, and those behaving improperly into healthy citizens was not confined to academic discussions but permeated approaches to law enforcement. In 1961, The US Bureau of Prisons organized a conference where the keynote speaker proclaimed that the “deliberate changing of behavior and attitudes” was possible when “relative complete control” was had over people’s environments (Story, 2005). The following year, Schein spoke at a symposium sponsored by the FOB and dismissed ethical questions pleading to focus solely on “deliberate changing of behavior and attitudes” (Chavkin, 1978) The power of such control was reaffirmed in 1963, when Stanley Milgram published the results of an experiment that demonstrated how authority figures could influence the acts of everyday life (Lemov, 2005). Milgram’s famous experiment alleged that authority figures could easily get ordinary people to commit horrendous acts. Milgram made explicit references to Germans and the Nazis in his paper. This experiment among many others (to be covered in future posts) convinced others that people’s behaviors could be changed.

Other developments suggested that refashioning sick criminals into healthy citizens was not science-fiction, but within the grasp of scientists. All that this transformation required was to understand the factors which increase the likelihood people would engage in criminal or undesired activities.

American Soldiers Support North Korea

American society was deeply shocked when North Korea released American Prisoners of War, who praised the communist regime and criticized America. Many American pilots gave confessions that reflected poorly on the US, and claimed to have engaged in germ warfare (Powell, 2021). Twenty-one freed American soldiers decided to stay in North Korea. Both Americans and North Koreans attempted to use POW to showcase the superiority of their systems (Powell, 2021; Keckeisen, 2002). The American POW confessions worried Americans. After the confessions some experts claimed that menticide had occurred (Young, 1998). The discourse about brainwashing allowed the military to avoid investigations about the content of those confessions (Young, 1998). The impact of the Korean War re-ignited the use of solitary confinement of prisoners with the aim of modifying their behavior (Story, 2005). The transformation of American soldiers into pro-communist advocates had a significant impact on American Culture.

The power of this episode in the American psyche is also represented in the films which depict prisoners of war (Young, 1998). Most of the films about Vietnam and the World Wars made both before and after the Korean War show POW’s resisting and refusing to collaborate with their captors. Nevertheless, the six movies set during the Korean War depict American soldiers collaborating with the enemy (Young, 1998). American audiences had seen American soldiers transformed, they now had real fears that Communist regimes would install or direct American officials. These fears came to life in a film called Manchurian candidate (Kushner, 2023). In short, the experience of seeing American POWs apparently betray their country, denounce American actions, and the choice some made to remain in Korea convinced Americans that brainwashing could really change people.

Guided Group Interaction, & Social Change

There were other demonstrations that suggested that soon people’s behaviors could be changed through science. Many of the technologies that the Seed used were understood to be cornerstones of successful attitudinal modification programs (Story, 2005).

In 1962, Dr. Edgar Schein, a professor of Organizational Psychology at MIT, specialized in Communist brainwashing techniques highlighted certain practices that contributed to the effectiveness of attitudinal modification (Story, 2005). These included isolating individuals and cutting previously existing emotional ties. Schein had said that effective behavioral modification also necessitated controlling what the target individual read and what activities they engaged in (Story, 2005). Programs within the military and penal fields suggested that behavioral modification was efficacious and desirable. Thus, there was enthusiasm for human engineering and a general sense that these technologies could effectively transform an individual’s personality.

During this time, criminal justice reformers also drew from the therapeutic community approach which saw drug abuse as a personality disorder (Kaye, 2019). Many professionals recognized that the reformulation of a person’s personality could be painful because it necessitated breaking protective barriers (Lemov, 2005). Chatfield traced the history of Guided Group Interaction (GGI), which was developed by the military and then found its way into society (2024).

In 1942, Military psychiatrists at an understaffed base at Fort Knox near Louisville, decided to combine sociological and psychotherapeutic methods to reduce undesired behaviors (Chatfield, 2024). The experiment at Fort Knox appeared to transform derelict soldiers into troops that were ready for duty (Chatfield, 2024). The program relied on confronting these individuals and pushing them to reform. The Army’s undersecretary of War was moved by their success and urged them to find civilian applications for these technologies (Chatfield, 2024).

The success of the military program to transform potentially court martialed soldiers into good soldiers, inspired similar transformations in other realms. Thus, the Highfields Experiment was born (post coming later). Here youthful offenders were put through intensive sessions where total honesty was demanded. This program used peer pressure, confrontation, and more. Initially, Highfields produced better results than regular detention (Chatfield, 2024). Thiss program was shorter and cheaper than current practices and their graduates had lower recidivism rates (Chatfield, 2024). Walter Cronkite made a two-episode special about the success of this program which featured program graduates (Chatfield, 2024).

Shortly, thereafter a series of trials known as the Provo experiments commenced. Inspired by the success of these programs, James Thorpe sought to apply them to treat adults who were addicted to cocaine (Chatfield, 2024) . Thorpe’s program uses terminology that is usually linked to Synanon, which shows that these approaches predate Synanon. Chatfield argued that over two decades of research and professional enthusiasm for guided group therapy “primed” politicians and professionals to endorse such an approach (Chatfield, 2024). Chatfield has defined therapeutic violence as “social infliction of intense discomfort or pain under the banner of treatment. These developments provide specific reasons why these kinds of approaches were seen as legitimate and efficacious. As a result, delinquency and addiction came to be seen as inextricably linked. This view saw addiction as the cause of crime and delinquency, rather than its result (Chatfield, 2024).

Reforming Through Treatment

In this period, there were several efforts to reform prisoners through similar programs. In 1968, Dr. Martin Groder developed a prison program, which he called Asklepion, that used transactional analysis and confrontational therapy to reform prisoners (Chavkin. 1978). In 1968, OJ Keller, known to be enthusiastic about GGI, took a position as Florida’s Division of Youth Services. Keller founded Dadefields and enacted reforms which included centering youth facilities around this approach. Synanon the game, the Seed’s rap sessions both were derived from Guided Group Interaction (GGI).

Synanon does appear to have inspired some centers (Kaye, 2019). Barry Sugarman, a sociologist, who led Marathon House spoke openly of totalitarian control to shorten the time it would take people (Kaye, 2019). The use of GGI is one of the Seed’s “outstanding strengths” according to an October 1972 report by Florida’s State Drug Abuse Program (FL DAP, 1972) . Hardy and Cull were also impressed by how the Seed used this technology. In a recent interview, a former staff member at the Seed said he is ashamed of what happened during his time working there; however, he clarified that at the time, “I was very, very proud of being part of such a dramatic great program” (interview) Chatfield raises an important question; namely why did many of these centers repudiate medical professionals despite the existing enthusiasm for these kinds of interventions? (Chatfield, 2024)

Powerful and Dangerous Tools & Ethical Concerns

The apparent efficacy of these tools raised concerns about how these technologies could be abused. In 1974, the US Congress tasked a subcommittee with investigating the State’s involvement in behavior modification which was headed by Senator Sean J. Ervin. He was deeply concerned about the possibility that these technologies gave a man the power to “impose his views and values on another” and thus be able to “dictate the values, thoughts, and feelings of another” (Chavkin, 19748). Implicit in his concerns is the belief that this was not only possible but close to becoming a reality. This report also disparaged The Seed and other institutions using similar tools by claiming that patients there faced similar treatments as American POWs during the Korean War (Kaye, 2019). This metaphor was especially powerful given that Americans remembered seeing American POWs transformed into North Korean propaganda agents (Powell, 2021). Importantly, these concerns question the ethics of these tools while assuming they are efficacious.

This series of powerful experiments and demonstrations were celebrated by some and terrified others. Many of these programs were pitched as pre-emptive or rehabilitative yet many feared that they were really aimed at mind control (Chavkin, 1978). In 1974, the director for the Commission for Racial Justice of the United Church for Christ published an article where he denounced technologies being used to modify behavior at Vacaville and Pauxent prisons (Cobb). He argued that these technologies were used to turn prisoners docile rather than to rehabilitate them. Moreover, he feared these could be used against civilians to “eliminate political dissidence” (Cobb, 1974).

In 1978, Samuel Chavkin, a journalist, wrote Mind Stealers to express his concern about behavioral modification and its potential for abuse. He was concerned that these approaches were no longer confined to criminals but that they were being used against others (Chavkin, 1978).

In this book, Chavkin outlined why he was concerned about the use of these tools against “mental patients, hyperactive children, homosexuals, alcoholics, drug addicts, and political nonconformists” (Chavkin, 1978).

Chavkin claimed criminals were no longer being prepared to live outside the prison; instead, the State sought a total alteration of prisoner’s personalities by making “submissive, unquestioning, and unchallenging” (Chavkin, 1978). He admonished several programs including The Seed.

Chavkin is concerned because he thinks that these technologies are either effective or will soon be effective. The book addressed Jose M. Delgado’s widely popular bull demonstration. In 1963, Delgado stood in the middle of a bull-fighting arena and was able to stop a charging bull by pressing a button that caused a surgically implanted device to release electricity in the bull’s brain (Chavkin, 1978). Delgado claimed he had not only localized violence in the bull’s brain, but that he was able to prevent the bull from being violent.

Delgado hoped that he would be able to build a Stimoceiver, a tiny device implanted in a person’s brain which could change emotions and control behavior. This device would be used to stop people from behaving improperly and allow the formation of a psychocivilized society. Chavkin was staunchly critical of these efforts but thought they could be effective (Chavkin, 1978).

In contrast, Elliot Valenstein, a neuroscientist, and psychologist, dispelled these fears in Brain Control. Valenstein criticized those who spread unfounded fears about the alleged power of controlling minds. He thought the science behind such claims was poor. Nevertheless, the fact he felt the need to publish two books addressing such fears suggests how widespread these ideas were. Moreover, they point towards an intellectual and social environment in which programs like the Seed would seem promising to some, and dangerous to others. Having explored this context, our next post examines discourses about the key interventions used by the Seed.

We are interested in speaking to other Seedlings. If you were at the Seed and are willing to have a conversation about your experiences please email us at: curingcrime@icloud.com

Acknowledgements: Christian wrote his masters project on The Seed for his ALM degree at Harvard Extension. This work draws heavily from that project.

A Job WELL DONE.👍🏼✅