Restricting Undesirable Immigrants

Exploring the Johnson-Reed Act of 1924.

Exploring the Johnson-Reed Act of 1924.

The most restrictive immigration bill in American history was enacted in 1924. This bill used biological justifications to restrict immigrants of undesirable qualities and backgrounds. Previous efforts to curtail immigration were justified using economic arguments. This bill was different and had a profound effect on American history.

Historians have offered an array of explanations for why the Johnson Reed Act passed. Some argued that these restrictions were driven by nativists (Shenton, 1990), and others that they resulted from scientific racism (Issit, 2008). For some, these laws were about race, (Paul, 1995) which others find too simplistic (Ngai, 2003). Many of these arguments attribute these restrictions to the work of specific scientists, such as Madison Grant (Spiro, 2009), or Henry Laughlin (Bruinius, 2006). We explore the 1924 Immigration Act in a series of articles.

A brief history of immigration to the US

The United States had, for large parts of its history, welcomed any people who were interested in coming (Laughlin, 1920). European immigration had originated mainly in Northern Europe, which changed in the late 19th century when newcomers from other places started to arrive (Paul, 1995; Okrent, 2019). These peoples were often referred to as “new immigrants.” There was also an increase in the number of migrants who came to the US.

The increase in the number of immigrants who landed in the United States engendered numerous attempts to restrict immigration, which progressively multiplied the reasons to exclude certain individuals. In 1829 there were fewer than ten thousand immigrants (Mayo-Smith, 1888). Millions would arrive by the turn of the century.. Soon thereafter more and more people would seek to emigrate to the United States.

The US welcomed about 10 million immigrants between 1820 and 1880 (Paul, 1995; Shenton, 1990). Over the next forty years over 27 million immigrants entered the United States (Paul, 1995; Shenton, 1990). Within the first eight years of the new century about six million immigrants arrived comprising 27% of the total number of immigrants who had ever landed in the US (Spiro, 2009). In 1907 the US admitted the largest number of immigrants ever (Trent, 1994). The trend was clear: more immigrants arrived each year. The continued arrival of immigrants inevitably had an impact on American communities and the economy.

Immigration Restrictions

1882 Bill: restricted Chinese immigrants based on economic concerns. thus making such restricting normative (Ngai, 2014)

1891 Bill: banned “idiots” paupers, people likely to become public charges, and “insane persons” (Okrent, 2019)

1917 Bill: used a sanitary lens to determine whether immigrants would be admitted. Also introduced a literacy test which was vetoed by the president. This restriction was meant to decrease certain kinds of immigrants (Bruinius, 2006)

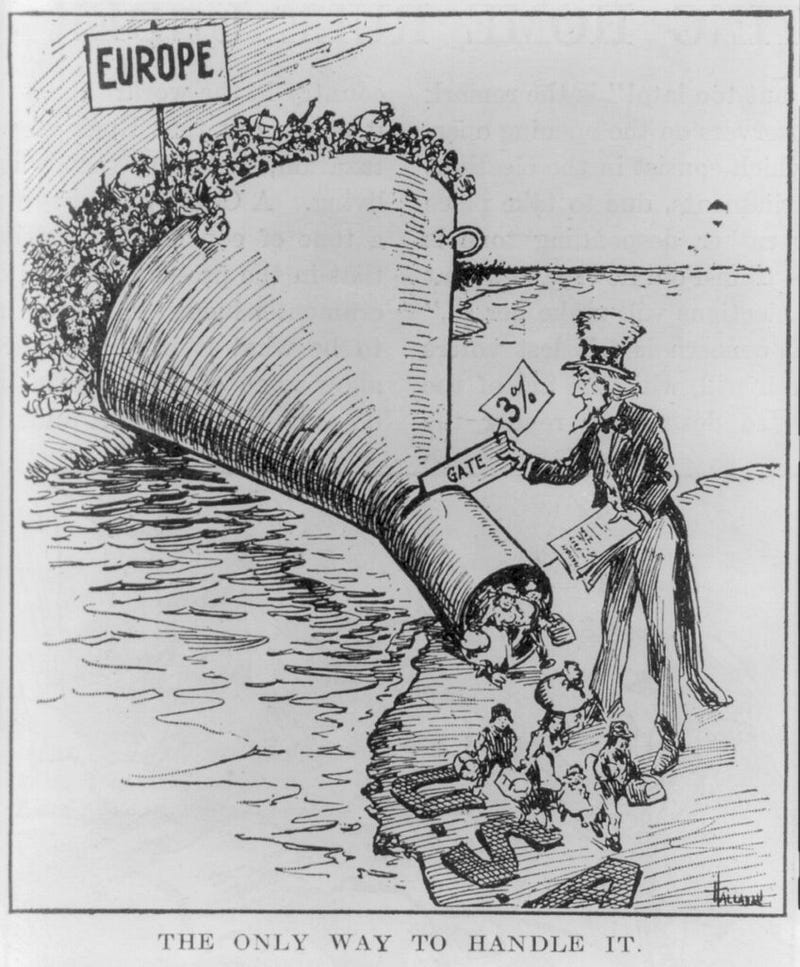

The 1921 Bill: passed as a temporary measure (Trent, 1994). It was the first to impose quotas limiting the number of people that could immigrate to the US from specific nations (Paul, 1995; Ngai, 2014). The limit was set at 3% of those living in the US according to the 1910 census (Paul, 1995). For example if there were 1000 Italians in the US according to the 1910 census then 30 could be admitted each year.

The Johnson-Reed Act

The Johnson-Reed Act of 1924 was the first to introduce permanent restrictions based on country of origin (Trent, 1994). The 1924 bill reduced the quota allocated to each nation to two percent of the total number of people of each nationality in the United States. Significantly it used the 1890 census rather than the one from 1910 to establish limits (Paul, 1995). The bill “heavily” reduced the quota for Southern Europeans (Stern, 2005; Jackson, 2006) because most of these new immigrants migrated after 1890 (Bruinius, 2006).

The change from the 1910 to the 1890 census lowered the proportion of Southern Europeans from 45% to 15% of incoming immigrants (Ngai, 2014). This bill passed with the support of scientists like Davenport, Laughlin, and Grant, who argued that biological concerns should drive immigration policy rather than the economic analysis which drove previous laws (Laughlin, 1920; Laughlin, 1924). However, we argue, the main drivers of restriction were economic and social rather than biological, despite the claims by eugenicists that the latter should determine policy (see our series Old Fears, New Foes).

Efforts to enact country-based quotas had repeatedly failed. Sitting Presidents vetoed the literacy test in 1911 and 1915 (Rosen, 2004; Nagi, 1999). The literacy test took fifteen years after President Grover Cleveland’s veto and required a congressional override to become law (Okrent, 2019). These failures suggest that the issue was more complicated than a simple discussion about biological quality. Americans were divided, and many opposed restricting immigration until the 1920s (Allerfeldt, 2010). Immigration restriction only became possible when scientists provided biological justifications for pre-existing anxieties.

Authors: Christian Orlic & Lucas Heili

This article is based on a paper written by Christian Orlic for one of his graduate degrees.