Exploring Virtual Criminology in the Darkest Files

The Darkest Files is a Video Game About Prosecuting Nazi Perpetrators

If from this lofty vantage point one views below

your far-flung realm, it seems an ugly dream

in which Deformity holds sway among deformities

and Lawlessness prevails by legal means

Faust, Part II

Criminology and criminal law have long fascinated people, prompting them to explore them through the media. From Sherlock Holmes to Anatomy of A Murder, to Ace Attorney, the process of catching and convicting a criminal (often in highly dramatized form) has been of great interest to the public for the last century. Whether consciously or not, they all contain a certain logic around why people commit crimes and how they get their comeuppance.

The Darkest Files, a historical detective game set in post-war West Germany, offers the modern player the chance to relive the unsung battles for justice in the courtroom, with all the obstructions, disinterest, and outright hostility it faced in its own time. By asking these same questions of why crime is committed and how it is caught, it allows for a discussion regarding historical perspectives on the trial of Nazi crimes.

In the game, you play as Esther Katz, one of three fictional prosecutors in the team of real-life Hessen Attorney General Fritz Bauer.1 Your job, a decade after the collapse of the Third Reich and the trial of the ‘big fish’ at the Nuremberg Trials, is to investigate and prosecute Nazis who have evaded judgment and are living regular lives in West Germany.

The gameplay loop revolves around calling in witnesses and suspects to the crime, literally investigating their memories as a physical space. By critically cross-examining their testimonies with various documents—police reports, relevant Nazi-era legal codes, personal notes handed in as evidence, and so on—you build a case to identify the real perpetrator, their motive, and how they knowingly broke the law. The gameplay enters into conversation with the ideas put forward by its real-life inspiration in three main ways. In doing so, it prompts the player to think about broader issues in the representation of history and criminology in media.

First, the game asks the player to consider the complicity of West German society and its conflicting and often complacent attitudes towards seeking justice for the victims of National Socialism. It uses the player’s presentism, their consciousness of Nazi crimes, to problematize Germany's post-war reluctance to investigate these crimes. This is all done through metanarrative and background historical elements that the player is passively immersed in.

Second, it also uses the interrogation of fictionalized witnesses and suspects, provoking the player to consider the motivation for Nazi crimes, not of the high-ranking ‘desk murderers’, but of the everyday Germans who participated in the system.

In a future article, we will explore how the game’s virtual courtroom reflects Bauer’s frustration with positivist thinking and the difficulties of the court system.

Contextualization at Court and In-Game

In the same way, Bauer's team felt it necessary to contextualize the crimes in the Auschwitz Trials, so does the game in immersing you in West German society of the 1950s. Through newspapers and conversations with coworkers, you pick up on Germany’s place in an ossifying international order split by the Cold War, and follow along week by week the national political debates deciding just how exactly the new Germany should look. During the timeframe of the game, the recently constituted Federal Republic of Germany was under the stewardship of Konrad Adenauer, who historian Jeffrey Herf characterizes thusly:

[Adenauer] believed that the best way to overcome Nazism was to avoid a direct confrontation with it while transferring ever more authority to German political leaders. Economic recovery and political legitimacy, not additional purges, were the proper medicine. Democratic renewal went hand in hand with silence and the forgetting of a dark past. Too much memory would undermine a still fragile popular psyche.2

Adenauer believed that achieving a democratic, pro-Western Germany “could entail less denazification, less purging, fewer trials for perpetrators of the Holocaust and war crimes, and less reflection on that history from the political leadership”.3 The move was seen as a correction to what many Germans saw as overzealous ‘victor’s justice’ by the occupying powers and a pragmatism to maintain the regular functioning of German society. The Allies’ denazification process involved events such as the Nuremberg Trials, intended to leave a public impression, but also involved more laborious and methodical methods, such as the processing of all adult Germans through denazification courts4

While imperfect and pockmarked by instances of realpolitik, such as Operation Paperclip, the Allies could impose these stringent conditions precisely as occupiers. A government beholden to the German voter had to reject a process of this scale if it wished to maintain its democratic mandate. Thus, with Adenauer, a reckoning with Germany’s past was abandoned in lieu of maintaining a continuity of everyday life and development.

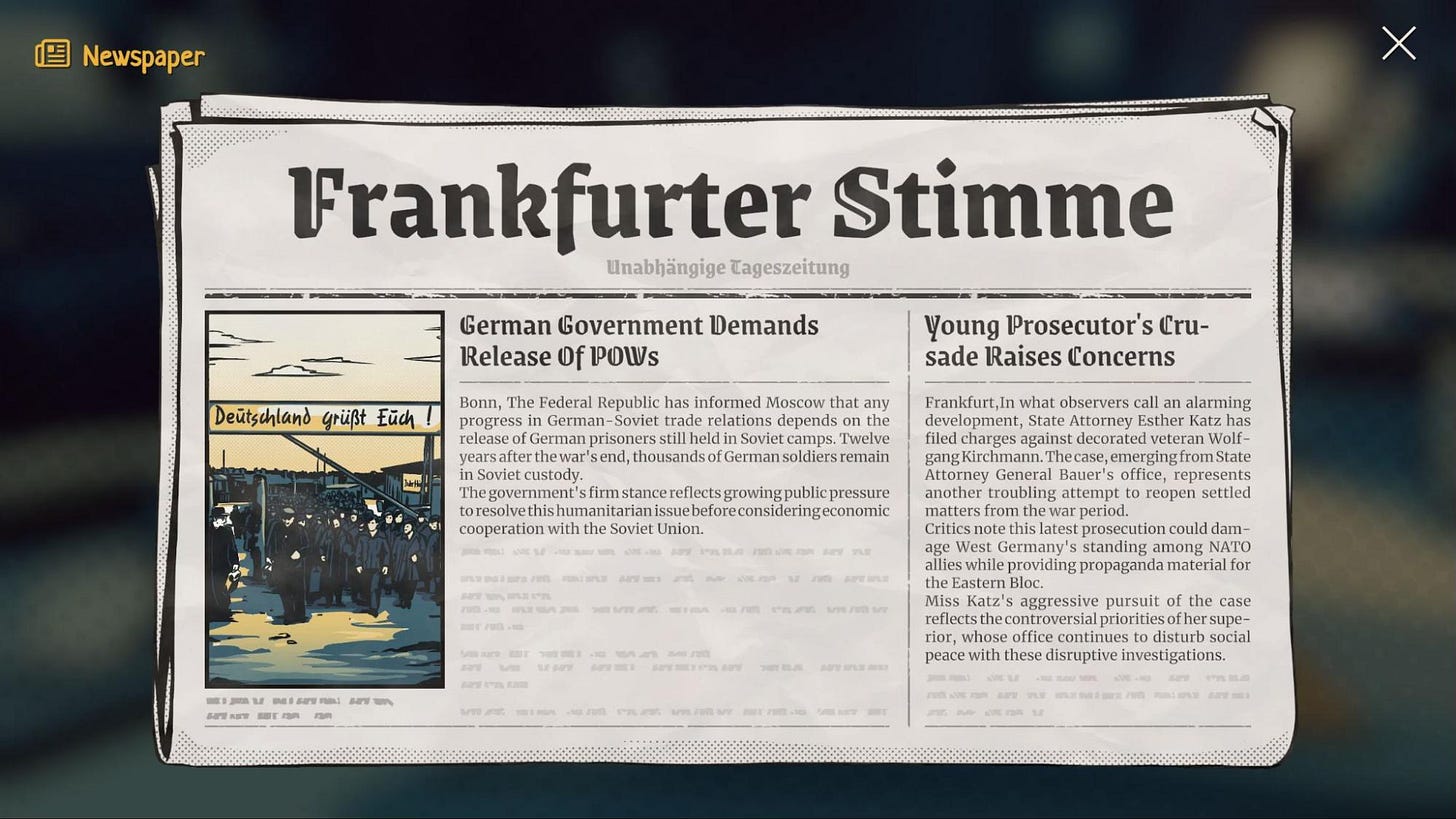

The newspapers scattered around the office in-game serve to make the player aware that they are swimming against the tide, that despite whatever innate goodness we, as the modern audience, associate with bringing Nazism to task, those values were not shared by either the state or the society of the time. Some of this was born out of necessity; for example, when instituting a new police force, former policemen had to be recruited. In the industry, many experts also collaborated with the Nazi regime, and thus it was hard to fully denazify the nascent state.

From the beginning, the game emphasizes that the lack of resources at the player’s disposal is due to the public’s and the government’s disinterest, verging on active hostility. Fritz Bauer’s team stands alone against the ‘politics of forgetting’ surrounding National Socialism.

To give an example, if the player reads the newspaper every day, they will follow the ascension of Hans Globke into the highest echelons of the Adenauer government. Even in the atmosphere of the immediate post-war period, his appointment drew raised eyebrows due to his responsibility for drafting and writing legal commentary on the Nuremberg Racial Laws.5

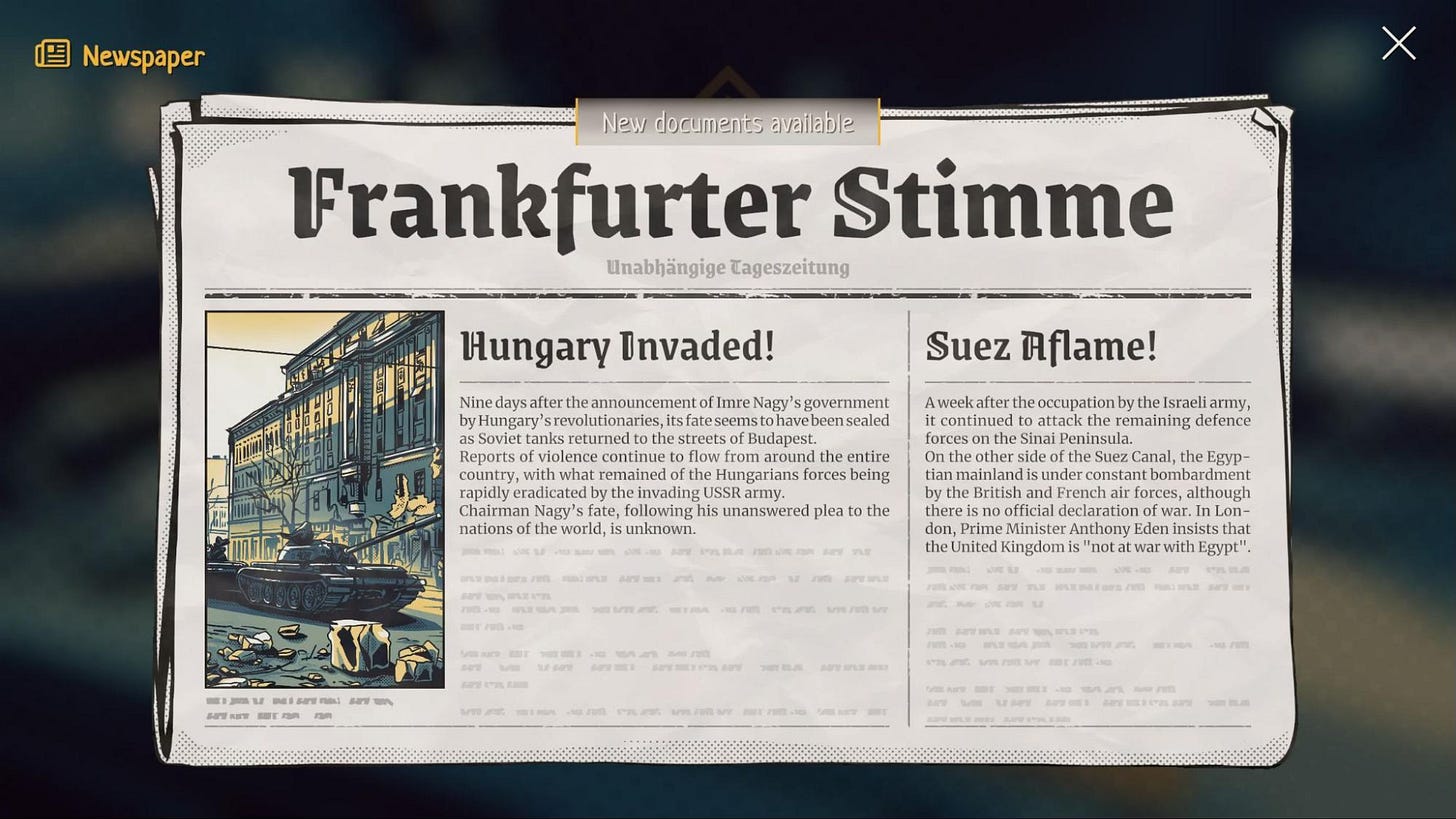

Other articles proclaiming “Suez Aflame!”, “Nuclear Weapons in Germany” or “Hungary Invaded!” make real the prevailing Cold War anxieties of the time. Two recurring topics concern the Suez Crisis and the nuclear arms race. These were being used as justification for the rehabilitation of former Wehrmacht members and their integration into the rapidly remilitarizing army, also covered in the papers.

The Suez Crisis gives a clear picture of how the young Federal Republic externalized its politics of forgetting through its alignment with the NATO bloc. Since the early 1950s, significant quantities of reparations, infrastructure projects, and military aid were provided to the recently founded state of Israel by the Adenauer government.6 Any sense of responsibility for the Holocaust (which was not shared among day-to-day Germans of the time) was done away with by transfixing its victims into aid for the Jewish state. Press coverage of the 1956 war makes evident the passing on of the torch of German military success as well, with Der Spiegel referring to “Israel’s Blitzkrieg” and “winning like Rommel”.7 The example ties Germany’s perceived repentance for its refusal to pursue National Socialism at home with its alignment with the Western bloc in the Cold War.

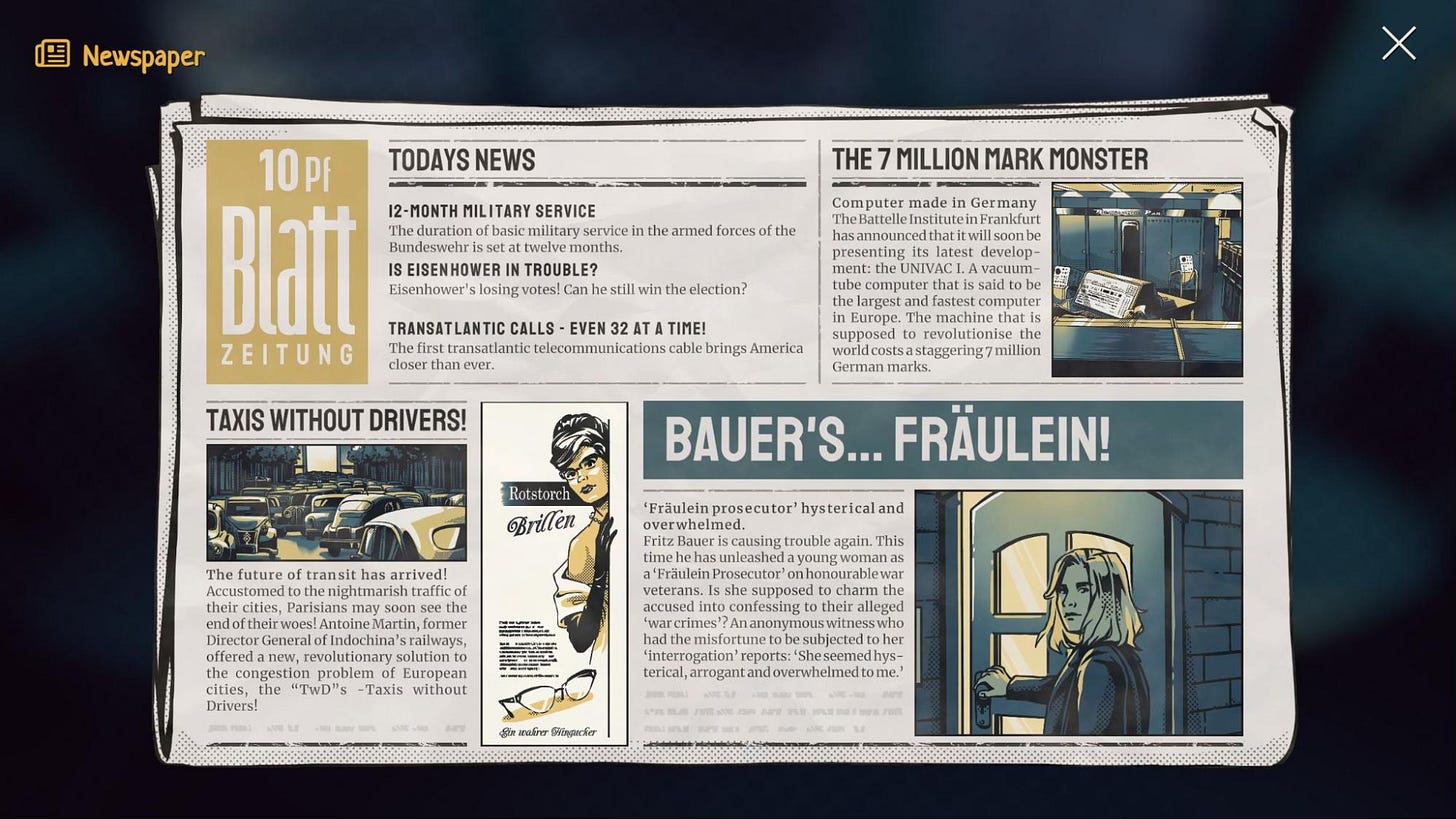

Another aspect that appears rarely in-game, but regularly frustrated the living Bauer, was a practice of forgetting through sensationalization. Considering prosecutors could only reliably pursue a murder sentence for those who committed extraordinary violence, cases such as the Frankfurt Auschwitz Trials became focused on individually sadistic actions and not “by the book” murder. Newspapers reported on details of brutal beatings, unnecessary torture, and individual cruelties by individual camp guards. While the game understandably wishes to center the active opposition to de-Nazification that plagued Germany, the press also worked in more subtle ways to distance the public from a sense of collective guilt.

German newspapers accordingly focused on the pulpy shock factor, on individual “monsters” at the camp, exculpating themselves from the mundane monstrosity of the camp system itself.8 Fritz Bauer, however, contended that “Nazism did not fall from the sky”.9 To blame the camp guards for their excessive cruelty was to miss the forest for the trees, to ignore the system of extermination itself. It drew a clear line between a monstrous few and the majority that quietly went along with Nazism, a rationalization Bauer worked tirelessly to disprove. The narrative was nevertheless popular, as it served to exculpate wider German society from accountability.

In the game, transmitting the broader historical context is not limited to newspapers. It is also woven through the protagonists’ interpersonal relationships. Most salient are the phone conversations Esther Katz has with her parents. Her father is a judge by profession and constantly chastises her about her choice of work. Her parents are both disappointed that she would not pursue more lucrative practices through her father’s connections. To drive home its point about the continuity of Nazism, the game allows the player to discover that her father’s success is owed mainly to his role as a judge under the National Socialist government.

The Darkest Files also plays with its fictional nature through Katz herself. In reality, there were no women on Bauer’s prosecutorial team. By bending this truth, the game can instead explore the very real barriers women faced at the time, coming barely a generation out of a government that only recognized the German woman’s place as wife and mother. Several suspects, and even one coworker, regularly speak to Katz condescendingly. Her parents, beyond being disappointed, are critical of the unwomanly nature of her public role.

While The Darkest Files’ gameplay is naturally confined to the world of interviews and documents, the newspapers, phone conversations, and chats with coworkers create for the player a sensation of the world outside of the office. This is not done solely for immersion’s sake. The news lets the player peer into the zeitgeist of a society whose concerns diverge significantly from those of the character, and likely the player. By situating the player within a society invested in forgetting, and by demanding that they pursue justice within a system unwilling to deliver it, it lends a serious moral weight and attachment to their objective.

Motivations for Nazi Crimes

What, then, does the game argue was the motivation for Nazi crimes?

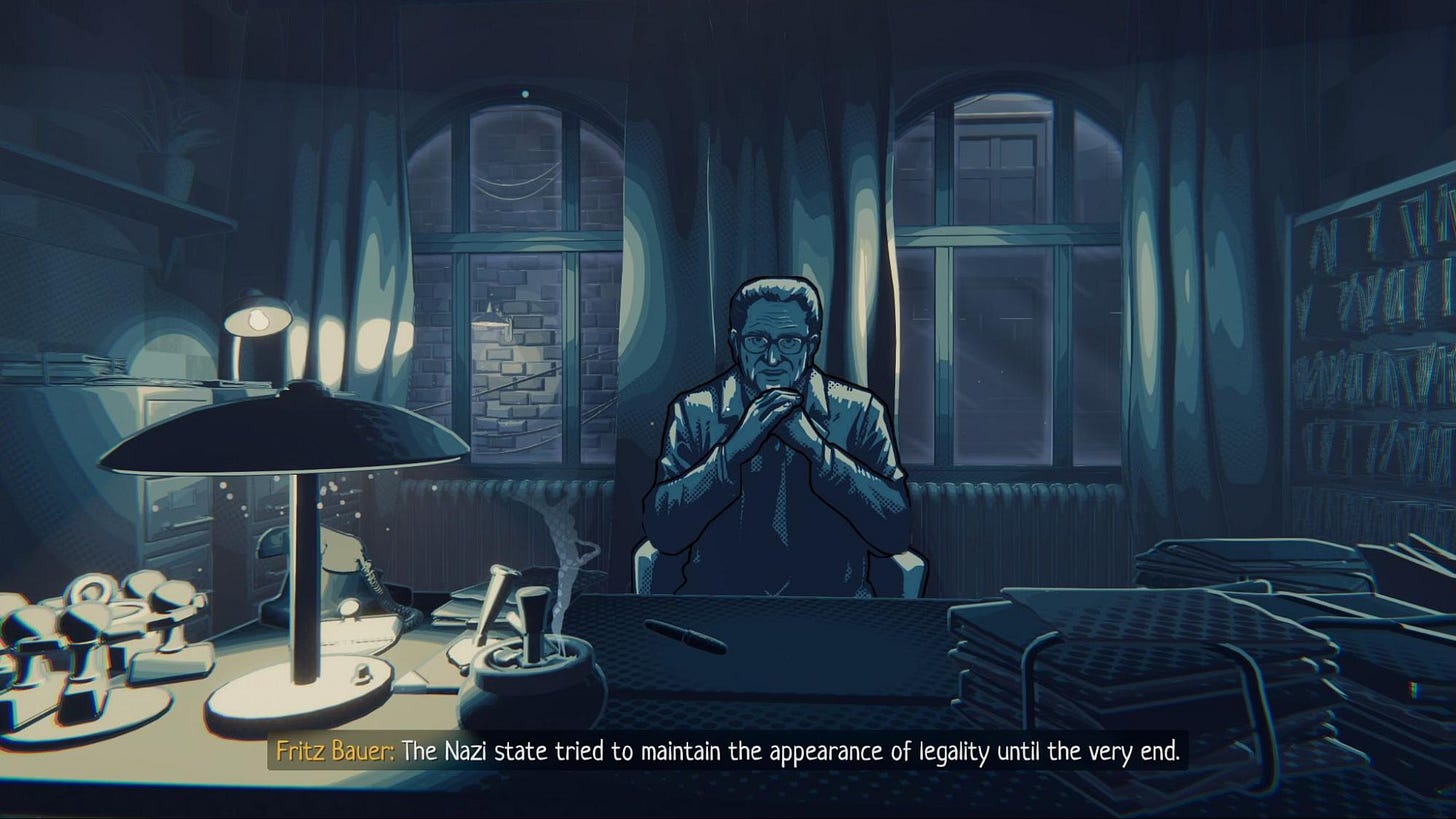

The in-game Bauer describes it as “human pettiness given power”. His flesh and blood counterpart stated that in the National Socialist state, “[e]veryone stood in a hierarchical order that gave them the opportunity to project themselves as the strong man over the next stratum and thus vent their inferiority and feelings of inferiority”.10

Bauer described Nazism as an unrechtsstaat, an unlawful state whose own organs have become criminal in violating the sanctity of life and human dignity.11 This system was able to arise, according to him, due to a historical German deference to authority and legal positivism: a deification of the law, a law that could be altered at will by the state, but which nonetheless remained above its jurisdiction.

By laying aside higher moral principles, criminal self-interest could be pursued by both the state and the small men of the Third Reich: “[m]asses are constantly on the verge of criminality; they possess a latent willingness to commit crimes. Nazism made it particularly easy for them because its leaders were themselves criminals and opened the door to certain forms of criminality”.12 At the same time, Bauer believed it was crucial to apply the latest findings from the relevant scientific disciplines— psychology, psychoanalysis, sociology, and criminology—to investigate the social and psychological factors that drive a particular individual toward a particular criminal act, even in the context of Nazism.13

The self-interest and resentment of the state were given preference over natural law. So the self-interest and resentment of thousands of Germans, each with their own particularities, was made known as they harnessed the violence of the state for their own purposes.

In Christopher Browning’s seminal work on the motives for rank-and-file violence under the Nazi regime, Ordinary Men: Reserve Police Battalion 101 and the Final Solution in Poland, he explores, among others, the case of Wolfgang Hoffmann. Hoffmann, a police captain and SS-Hauptsturmführer, goes to painstaking lengths to hide a bowel illness resulting from the psychological stress of conducting regularized mass murder from his superiors. The reason? To not harm his future career prospects in a leadership role.

In The Darkest Files, Nazi Party Local Group Leader Alfred Faltmann organizes the execution of the father of a partisan, passing him off as the son, to bolster his criminal-catching credentials and advance his career within the party. This opportunism is even hinted at in his documentation: he joined the NSDAP only a few months after Hitler’s appointment as chancellor in January 1933.

At the trial, the judge allows the player to speculate on the exact reason for Faltmann’s actions, giving them one of four responses that have no further bearing on the game. This multiplicity of causes in Bauer’s criminological thinking is reflected in these options, as well as the judgments the player makes delving into the case. The common thread enabling the crimes is ultimately the Nazi regime, while each individual had their reasons for playing along.

In Christopher Browning’s seminal work on the motives for rank-and-file violence under the Nazi regime, Ordinary Men: Reserve Police Battalion 101 and the Final Solution in Poland, he explores, among others, the case of Wolfgang Hoffmann. Hoffmann, a police captain and SS-Hauptsturmführer, goes to painstaking lengths to hide a bowel illness resulting from the psychological stress of conducting regularized mass murder from his superiors. The reason? To not harm his future career prospects in a leadership role.14

In The Darkest Files, Nazi Party Local Group Leader Alfred Faltmann organizes the execution of the father of a partisan, passing him off as the son, to bolster his criminal-catching credentials and advance his career within the party. This opportunism is even hinted at in his documentation: he joined the NSDAP only a few months after Hitler’s appointment as chancellor in January 1933.

At the trial, the judge allows the player to speculate on the exact reason for Faltmann’s actions, giving them one of four responses that have no further bearing on the game. This multiplicity of causes in Bauer’s criminological thinking is reflected in these options, as well as the judgments the player makes delving into the case. The common thread enabling the crimes is ultimately the Nazi regime, while each individual had their reasons for playing along.

The man who pulled the trigger, Karl Schickert, was handed down an accessory to murder charge—the very same one handed to ten concentration camp personnel at the Auschwitz Trials.15 He exemplifies the superior orders argument, claiming the repercussions for insubordination simply did not allow for them to refuse out of fear for their own lives. This argument was commonly used by those at the Allied trials, and was explicitly rejected by Article 8 of the Nuremberg Charter.16

In the game, Schickert’s case can be ruled out by showing he was punished for insubordination. Rather than being executed himself or sent to the Gestapo, he was kicked out of the NSDAP—hardly a punishment that would force someone to comply for fear of their life.17 He objects initially to the execution, purportedly due to his deeply held Prussian values. His ultimate acquiescence, however, gives a clearer insight into the nature of those values: an obedience to authority and mass mentality, even at the expense of one’s moral principles.

The second case in the game makes clear another key aspect motivating individual crimes during Nazi Germany: resentment. It centers around a false accusation of looting originating from, among other factors, a romantic dispute mediated through the class and racial tensions of three families sharing an emergency shelter after an Allied air raid. Nazism was a successful capturing of a collective resentment that was then enshrined in the German nation itself.

Bauer describes how "inferiority complexes, vindictiveness, and fear erupted” in the Nuremberg Race Laws, meant to function as a kind of new basic law for Germany.18 There is an unmistakable psychological component that is not “merely” individual, but elevates the individual grievances of a nation to its guiding legal principles. In the game, you follow how the false report is taken as fact by the Ordnungspolizei without question. The policemen then extract a forced confession from the victim, sealing her fate, as if to bring this resentment into legal positive reality.

Through these cases, The Darkest Files explores the same criticisms of positivism levelled by the real-life Bauer, particularly how it acted as a shield in post-war Germany for Nazi crimes. This was the thinking that allowed the legal system to warp itself at will to fuel these politics of self-interest and resentment. However, that same logic opened itself to the type of scrutiny that is entrusted to the player: to identify these points of contradiction between legalized Nazi crimes and their failure to observe their own laws.

Conclusion

The Darkest Files synthesizes recent historical scholarship, the writings of Fritz Bauer himself, and even its own fictionalized elements to explore what criminality and law meant for the Nazis. The player’s investigations will have them trace petty individual motivations whose sum, eventually and off-screen, provides the necessary mentality for the Holocaust.

The game helps explore how a society can recuperate, or fail to do so, and hints at a more humane and just interpretation of criminality and law. The historical context situates what is an ordinary criminal trial on paper into an actual culture war within West German society. It ties together Cold War politics and latent national resentments to show how most Germans at the time still viewed themselves as victims, rather than perpetrators. For them, justice meant a return to normalcy without asking too many questions, rather than a true reckoning with their recent past.

We have explored how the game prompts these questions in a straightforward textual manner, through its background context, and via the events of the main story. In a future article, we will discuss how the game mechanics present realities and assumptions of causality, proof, and guilt that model German legal positivist thinking of the time in a virtual courtroom.

Fritz Bauer was a German-Jewish lawyer most well-known for his anti-Nazi activism and later prosecution of Nazi-era crimes upon his return to Germany. He was the Hessen Attorney General from 1956 til 1968, and in this position he conducted the Frankfurt Auschwitz Trials.

United Nations, “Agreement for the Prosecution and Punishment of the Major War Criminals of the European Axis (‘London Agreement’),” Nuremberg, Germany, August 8, 1945, 82 U.N.T.C. 280, United Nations Treaty Collection, www.refworld.org/legal/constinstr/un/1945/en/21123.