Curing Crime Origins

How We Got Here

We think studying crime and efforts to prevent it from a historical point of view is interesting and important. This study reveals how scientific and medical ideas make their way out of the laboratory and shape the world. They demonstrate that new technologies change how societies approach the problems they seek to resolve. This approach also highlights the social construction of crime. How is it possible that the same behavior is a criminal act in one place and not another? By looking at what societies criminalize, how they intend to reduce crime, and how they treat people convicted of committing crimes, we aspire to better understand those societies.

Our task is not to solve problems or even propose solutions. Our role is more humble, as we hope that through approaching these themes historically, we can shed light on how these initiatives impacted people and societies. In doing so, we can highlight questions, potential issues, and benefits that we think should be considered when designing solutions to social problems. Our investigations suggest that often well-intentioned and well-respected professionals offer solutions that are zealously embraced and that sometimes have disastrous unintended consequences.

How Did We Start?

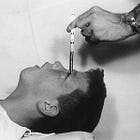

Christian: I have been interested in history and history of science for a long time. After teaching for a few years, I enrolled in a class at Harvard. During this class, I learned that Millard Wright, a habitual criminal, had been lobotomized to eliminate his criminal tendencies. I also found that he was not the only one. It was perplexing to me that an operation known to reduce inhibitions and that left some patients in a vegetative state was prescribed to cut on a behavior.

This article was based on the assignment that started it all. I examined the biography of Howard Dully. He was lobotomized when he was a child.

Years earlier, I learned about eugenics and other efforts to improve societies by changing their constituents or structures. Since the 19th century, it seems that nations have embarked on projects that take one of these approaches.

I started learning more about such efforts. It became clear that scientific and medical discourse impacted public discourses about crime and criminality, and I felt that this was a fascinating area to explore. I decided to create some kind of accountability, and after conversing with Lucas, we decided that writing was the best way to do it.

This was our first collaborative article, and we are happy with it. We have certainly revised our processes and work more efficiently, but we will always remember this one.

I’ve gotten more hooked on writing (and substack) since we started this journey, and it's encouraging to see a product from the reading and thinking that otherwise appears to vanish into the ether. I also feel like we are finding a community and we have been delighted to e-meet other writers and thinkers.

Lucas: Studying crime and its history was never in my plans. I was an undergraduate marketing student in Barcelona, going through a complicated financial situation during the pandemic, and I needed some form of income during my studies. It was hard for a foreign student to find a job in Spain, which led me to look into every possibility.

The first place that came to mind was universities. For weeks, I asked teachers whether they would take me under their wing for all sorts of projects until I got an email from Christian Orlic , a historian working on his master’s who was looking for a student to help him with some research projects.

I replied to his email, took the call, and began working. It was a perfect match, though an unconventional one. Christian was, and still is, mainly focused on studying the history of crime and the use of science to prevent it, whereas I was a marketing major looking to enter the corporate world. Despite these differences, I accepted the job, and he introduced me to the strange, sometimes morbid, but riveting world of criminology.

“He had no idea what he was getting into. Honestly, neither did I. What started as an exploration of lobotomy to cut crime turned into a much bigger project.”

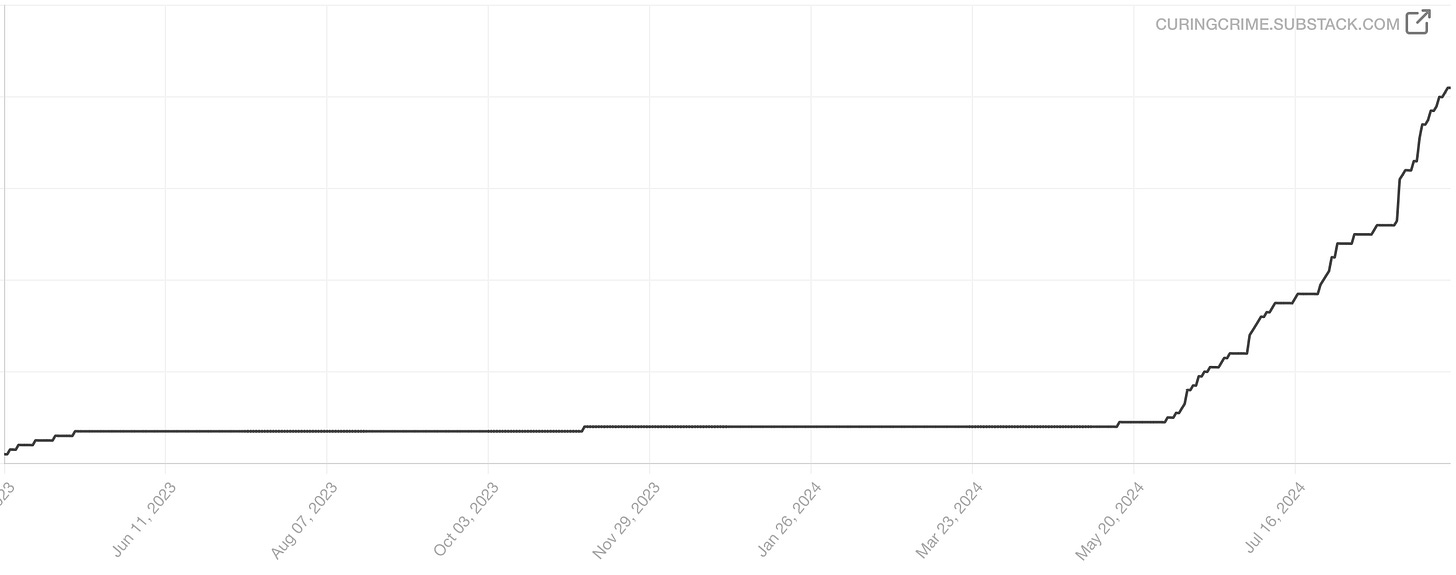

Having always been a writer at heart, and attempting on multiple occasions to write online for my personal enjoyment (if you speak Spanish, you can read some of my work here) while also seeing that we sometimes fell into patterns of unproductive working, I proposed to begin publishing somewhere the work we had done so far. That’s how Medium came into play. Later, after my ceaseless insistence on moving to Substack, we created this newsletter.

Christian: We did have that conversation at least ten times. I was wrong, admitted as such. Lucas can't seem to let it go.

It’s been four years since, and I have learned, not as easily as one would hope, to appreciate the study of this subject. Furthermore, as a result of this work, I began asking all sorts of important questions in my everyday life, not only concerning crime or criminology but on a more philosophical level. Today, I can say that, while it may not have been part of my plans when I first embarked on this journey, I am glad to have accepted that proposal all those years back. Seeing this project grow and get more attention is a very fulfilling venture.

Does Studying This Ever Get to You?

Christian: I have a fairly high tolerance from my years of reading history, but it absolutely does. There are a few moments that stick out to me. For example, in the late 1970s, a company advertised a remote that could wirelessly trigger a device to give a child an electroshock so the child would allegedly learn not to engage in a behavior. The existence of said device and the manner in which it was advertised made me think of the many students who have come through my classroom. How could anyone use electric shocks to teach a child? During lobotomy’s heyday, some doctors even advocated lobotomizing children. The third difficult episode was a conversation with a person who was interned at the Seed. The events she told occurred decades ago, but the scars they left were still there.

Speaking to survivors is the hardest. I want to honor their stories and they have valuable perspectives and experiences. On the other hand, I can see and hear their pain. It can be distressing to hear and think about them. I realize living through them is much more painful and that these stories are worth telling.

It is easy to forget that behind each device, each operation, and each theory, there were people. People with names, faces, dreams, and friends. I investigate a difficult topic that touches on difficult emotions and difficult events.

Are the criminals always to blame? Some criminals also appear to be victims of overzealous zealots hell-bent on reshaping society. For example, good people have been demonized for engaging in homosexuality, for crossing color lines, or for wanting freedom. Our forefathers punished behaviors we celebrate – are there any behaviors we currently punish that will cease to be perceived as criminal? Many crimes do have victims - serial killers did torture, maim, and kill people. Lastly, there is a systemic dimension which affects innocents and people who have committed crimes.

I do shudder, and sometimes, I need to go for a walk or find my partner's embrace so that I can briefly escape what I have just read. Other times, I put on some TV show that I find particularly funny or distracting. On the other hand, it gets easier as one gets used to coming across such materials.

Lucas: To an extent, yes. Looking into some of the dark corners of the history of criminology, science, and medicine can get quite uncomfortable quite fast. It is not cut out for all sensibilities, and I was certainly not cut out for it at first.

I have always kept a protective distance from the more gory and unpalatable aspects of history, but when studying this matter, it is impossible not to come across some of it. Therefore, over time, I have managed to compartmentalize the more disturbing aspects of what we study. Nonetheless, to this date, there are certain sources, texts, or pieces of media that give me chills.

Christian: One of the most striking aspects is that many of our subjects were not shocked. The fact that the same operation makes modern readers aghast used to fill readers with enthusiasm suggests there is something there that demands an explanation.

I remember reading The Dark Side of the House, a book on the case of Millard Wright, written by Dave Koskoff himself (the doctor who operated on Wright). And while the book does not dive too deep into the details of lobotomies, I was impacted by the positivity with which he addressed the effects of it. This man was literally inserting an ice-pick and shaking it as if making scrambled eggs in another man’s brain, later talking about the wonders it made.

This was far from the most graphic account I have read, yet surprisingly, how the procedure and its results were described disturbs me to this day. In short, sometimes it gets to me, though I can mostly keep myself from thinking too much about it.

Living History

We write about issues that continue to affect society and people who may be alive or who have living descendants.

Methodologically, we try to understand our historical actors under the auspice of their own time and endeavor not to judge them through the prism of our morality. If there is to be any hope that our work can help reduce unnecessary pain, suffering, and injustice, we need to understand the past not as a step towards the present but as open-ended with a kaleidoscope of possibilities.

We do not write about crime because it may be salacious, but rather to respect the stories of those who lived, breathed, and died. We find the intersectionality between science, medicine, criminology, and public policy interesting to explore, in part because it continues to shape our lives.

Some Resources

We announced this article was coming in Notes, and got some good responses. We wanted to share a resource via Aaron Jacklin: This site provides some advice on how to avoid vicarious trauma: Mental Hygiene.

This article was in part inspired by Sophie Michell and her kind engagement with one of our comments. She recommended: Whats In A Name?

PS. You can also read more about the work of Christian Orlic & Lucas Heili at our personal substacks, for a more refreshing insight into our ideas and our thinking.

Nice idea for an article, guys! I hope it generates a lot of engagement.

Excellent article. I think it's important to reflect on why we choose to study such unpleasant topics, it helps us keep sight of the humanity of the subjects and avoid becoming sensational.