Criminal Justice and the Body: Phonebooks, Torture, Sentencing, and Bodily Autonomy

The History of Crime Through the Lens of the Body

Last April I attended the ESSHC conference in Leiden, and saw some great researchers present fascinating work. This post is based on my notes and recollections of those talks1.

Phonebooks: Torture in the Interrogation Room

Elwin Hofman, a historian, says that policemen often say “phonebooks” when he tells them he studies the history of criminal interrogation. He studies the history of police interrogations when they investigate specific crimes. Supposedly, policemen used phonebooks to hit people during interrogations because these, allegedly, did not leave a mark2.

The first phonebook was printed in the United States in 1878, two years after the invention of the phone. The first mention of phonebooks being used in interrogations is from 1931.

This mention alludes to several reports during the 1910s and 1920s which accused American policemen of using physical violence during police interrogations. In 1929, President Hoover called for an investigation to determine whether such abuse was common, resulting in t

he Wickersham Committee Report. This report documented lots of police brutality including hitting people, the use of starvation, and such. The Wickersham report included the following remarks,“The Chicago telephone book is a heavy one, and a swinging blow with it may stun a man without leaving a mark.” During the 1920s some police chiefs argued that violence was useful during interrogations, but by the 1930s such abuse had become taboo.

Across the pond, Europeans strongly criticized the findings of the Wickersham report and claimed such abuse was impossible in their countries. In this continent, legal scholars, police manuals, and popular culture saw torture as something from the past. Most police interrogation books did mention that such methods were used in the 18th and 19th centuries, but claimed to have left these practices behind.

In his research, Hofman found no evidence that phonebooks were ever used by European policemen during the 1930s-1950s. He did however, find evidence that other forms of violence were used such as hitting subjects with gloves, starvation, and sleep deprivation. There are some reports from the 1970s-1990’s coming from retired police officers who indicated they saw someone else use a phonebook or threaten to use one, and rarely that they themselves had used one. He is scpetical because these accounts always claim someone else had used them. A French film, Les Ripoux (1984) depicted a senior police officer showing a younger officer how to hit subjects with a phonebook.

Hofman found the story of phonebooks interesting and perhaps a good entry point to studying the history of police interrogation. There was and is very little discussion about the types of cases where violence may have been used. There is and has been near universal public rejection of the use of physical violence by police. And phonebooks may have provided plausible deniability. The case also raised a paradox of modernity by mixing torture with a modern tool (the phonebook). Phonebooks disappeared around 2010. Like other periods in history, some police officers now refer to the abuse of phonebooks as a way to distinguish current practices from those of the past.

The spectre of physical abuse at the hands of the authorities is terrifying. The stories about phonebooks likely reveal much about this fear. Interestingly, phonebooks are now used as a way to distinguish current practices from those of the past. Like Hofman suggested, the use of such contrasts with the past can make it harder to reflect on current practices. They also illustrate that group identity is often definged in opposition to a caricature.

Gender and Sentencing Disparities in the Distant Italian Past

Lidia Zanetti argues that in the cities of Siena, Florence, and Bologna, Roman law “exerted an intense influence on the developments of criminal justice,” leading to different assumptions about the gendered nature of criminal bodies compared to other parts of medieval Europe.

Zanetti’s central inquiry—“was corporal punishment gendered in late medieval Europe?”—challenges widely held notions derived from studies of regions like Flanders and France, where women were more often burned at the stake while men were more likely to be hanged. Scholars have long debated these disparities: some point to concerns about the “indecency of displaying female corpses,” while others suggest that female criminality, especially in cases of witchcraft or infanticide, was interpreted through a demonic lens that called for burning.

Zanetti’s work is grounded in Roman legal traditions, particularly those codified in the Corpus Iuris Civilis, a foundational body of Roman law compiled under Emperor Justinian in the 6th century. These laws were formally gender-neutral—criminal intent (mens rea) was judged similarly regardless of sex. She examined 331 death sentences in Siena, Bologna, and Florence from the 13th and 14th centuries, only fifteen of which involved women. Of these, four were cases of infanticide.

What makes Zanetti’s study compelling is her attention to how legal codes interact with judicial discretion. Roman legal tradition allowed judges to supplement statutes through arbitrium, especially in cases involving premeditation, betrayal, or familial crimes. These practices were sometimes codified locally, as seen in the 1359 Statutes of Forlì:

“Since it is worse to kill someone with poison than with a sword, we thereby establish that if a man or a woman murders someone with poison, they shall be burnt at the stake.”

The statute is striking in its gender symmetry—underscoring Zanetti’s broader point that, in these Italian cities, execution methods were less influenced by gender norms than elsewhere.

Ultimately, Zanetti calls for an historical approach that bridges legal, cultural, and bodily histories. Although statutes often treated men and women equally, and execution methods did not significantly differ by gender, she notes that perceptions of gendered bodies could still influence criminal proceedings in ways not explicitly codified in law. Her work invites us to see medieval justice not simply as law applied, but as law interpreted—shaped by culture, emotion, and embodied assumptions. Zanetti’s work is helpful in thinking deeply about history and considering both theories and practices.

Bodily Autonomy: The Lack of Clarity is Problematic

The latter part of the 20th century saw the emergence of the right to bodily autonomy and thus restrictions on how far the police or physician can search on or into the body.

This section is based on the work of Willemijn Ruberg, who is a cultural historian interested in the cultural history of human rights. He thinks that the rights of bodily autonomy are really unclear including who has these rights. Thus, his work examined the history of bodily autonomy, who deserved it, and what it constitutes.

Currently, in cases of prostitution there almost always is a compulsory investigation of the women’s body. Several feminist scholars have critiqued this practice as a violation of the woman’s right. In the past, the sex worker’s body has often been portrayed as an object to be studied, and it has been assumed that they would feel no shame because of their line of work. Further, this view also held them as the source of sexually transmitted diseases. This practice was abandoned because it was seen as ineffective, and not out of care for these women’s rights.

Another case dealt with Sinti and Roma people in the Netherlands. The police rectally examined the man, and the woman’s vagina was also searched. The police were searching for passports so they could return these people to their home country. During a session in parliament Justice Haaretz declared “it is simply known that gypsies, when they have something to hide, hide things in their bodies.”

The fight for bodily autonomy is “anchored in the Dutch constitution discussed from 1976, accepted in 1980 and in force from 1983.” This has an interesting party because it passed through the collaboration of strange bedfellows, a group of protestants that were against being forced to take the polio vaccine, and a group that sought to prevent forced sterilization, electroshock, castration, and more. In contrast, police is often seen as able to take bodily samples. A Spanish Man in 1986 was rectally examined at the airport because the police suspected he was carrying drugs.

Other cases may include drunk driving. Can drivers be forced to provide samples? What about DNA? How we determine what rights exist and how has them impacts how authorities treat different groups of people.

According to Ruberg there is a lot of uncertainty about bodily autonomy. Even in cases where it is anchored in the constitution, it may not be expressed in other laws. There is also often a grey zone that is up for negotiation and hence sometimes not applied to some groups. He is working on a cultural history of human rights based on practices rather than proclamations.

This discussion can hopefully illuminate how thinking through historical cases can help us thinking about present cases or issues. We create immense digital fingerprints which companies, governments, and others could access and utilize. The potential also exists for deeper investigations of the body as genetic technologies develop.

Punished Bodies in Madrid 18th & 19th Centuries

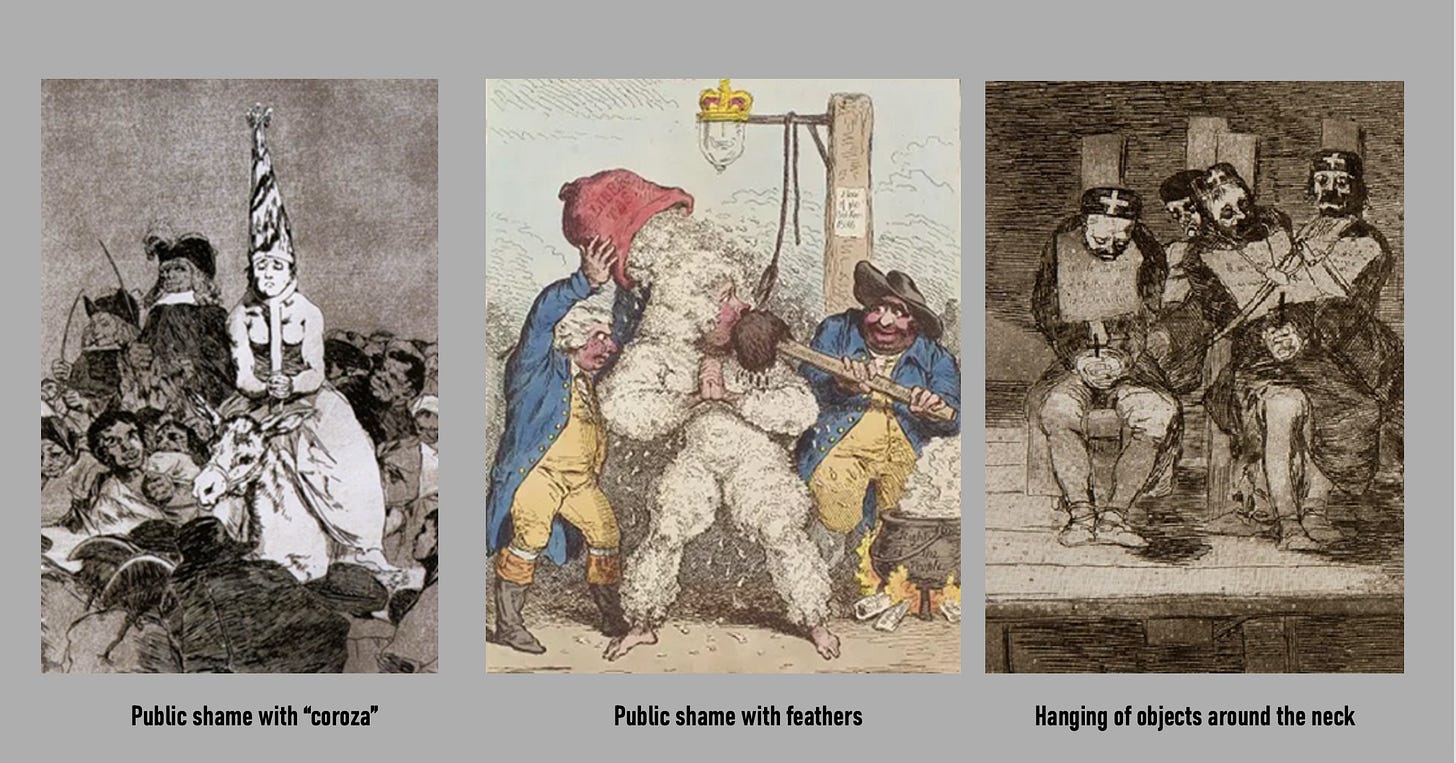

The use of public and physical punishment is often described as barbaric. This was not always the case. In fact, such punishments were often used. Francisco Cubo claims that afflictive punishment and execution were the “greatest exponents of exemplary punishment” in Castile and Madrid until the mid 19th century.

At the time the only criminal legislation were the Alfonsoan Partidas. They established punishments as a means to amke ammends for crimes. The Spanish Crown had continued to mutilation and perpetual branding up to the18th century (including mutilating limbs, cutting the tongue, and others). However, since the 16th century there had also been discussion about restricting the abuse of torture to obtain confessions.

The spread of ideas related to the enlightenment described these kinds of punishments as “uncivilisation and barbarism.” These criticisms called for more utilitarian punishments, yet most proponents still had no problem with prisoners escorted to their execution in front of crowds.

In general the whip or drumsticks were mostly used on men, and shame was more often used on women. Francisco Cubo has found examples of these being used up to 1834. As part of his doctoral work, Cubo has found 300 cases of whipped individuals, more than 80 shamed ones, and 700 condemned to death between 1751 and 1834. His research revealed 327 cases where people were condemned to be flogged (constituting about 1.3% of all punishments given in Madrid). His archival studies show an increase in the use of public punishments between 1751 and 1823. Some who attempted escaping from prison were whipped. Other prisoners were made to walk under the fallows, and others had signs hanged around their necks. These kinds of sentences decline after 1834.

Cubo suggests that “while the ritual of public execution existed, the scorn and shame of the condemned also existed alongside it, in an intrinsic manner. Perhaps without feathers or chorus, but with other alternatiees that adapted to the new times.” His suggestion is that these elements remained inherent in executions despite historical actors claiming they had abandoned such practices.

This study of psychological and physical punishment in Madrid adds to our understanding of criminal proceeedings and pushes us to think about the ways in which criminal justice may preserve barbaric elements of times past even when these elements have been repudiated. Archival research continues to be incredibly revealing.

*While I took notes on my iPad, these were short talks and the pace was quite quick. Hence, I may have inadvertently made a mistake in transcribing or interpreting my notes.

For those that do not know, phonebooks used to list phone numbers. There used to be yellow pages where business advertised, and white pages which listed people’s numbers.

Yep, I remember Vic Mackey of the Shield's first episode hitting a suspect with a hefty phone book in the interrogation room to extract the location of an abducted child from the guy. The captain look on over video but shut it down as soon as Mackey started hitting, quietly endorsing it.