Crime, Gender and History

Thinking Deeply About Gender and Crime

Dear Readers,

In this issue, we explore exciting research on crime-related topics, including sentencing, justice, and gender1. Drawing on recently presented work, this post discusses whether women were treated more leniently in the courts, the difficulties in inquests examining infanticide, and how political considerations affected decisions to grant mercy to death row inmates.

We begin with two different studies that investigate whether crimes committed by women are treated differently. Both Sophie Michell and Brown find that what initially appears to be a case of gendered justice is actually a product of different factors. Brown found that the women perpetrators were not treated differently by the courts and that narratives in the press were not gendered. Similarly, Michell unveils that inquests involving infanticide faced challenges beyond the gender of the accused, such that determining whether a homicide had occurred was especially hard. Finally, the third researcher, Neale, found that the UK’s government decisions to forgo the death penalty in some instances were motivated by a series of reasons.

It’s All Moonshine: Sex, Social Class, and the Stereotypes at the 19th-century England Inquest.

19th-century Victorian Coroner Courts have been accused of being unjustifiably lenient when determining whether to indict women suspected of killing their neonatal children. While the scholarly work in this subject is scarce, there are some suggestions that women could get away with infanticide. In contrast, Sophie Michell argues that this ignores how complex these inquests were.

Michell proposes that these complications can account for statistics that suggest that women could get away with it. For example, in Peterborough, out of thirty-three cases, only six were ruled homicides. Before we explore these complications, we need to contextualise these inquests.2

At that time, alleged homicides were first publicly examined by a coroner’s court that decided whether “the deceased was a victim of homicide, and whether they could name a suspect.” If they answered both questions positively, then it became an indictment that bound the suspect to trial. The first question required them to answer:

Was this death natural?

Was there anyone to blame?

Was the death inflicted?

Was the suspect insane?

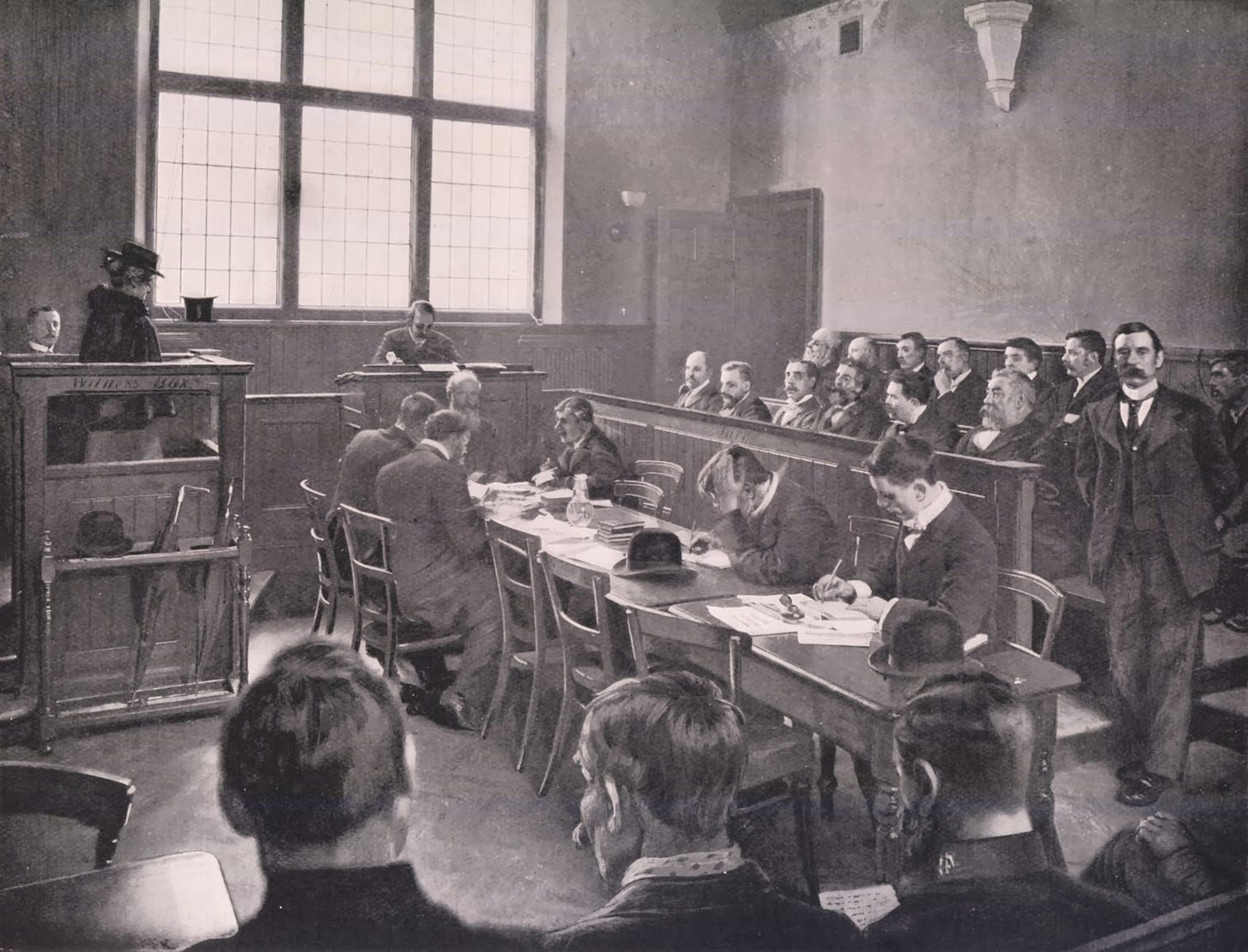

Coroner courts would meet very suddenly after there was suspicion of homicide. These courts were composed of a coroner and a jury, comprising twelve to twenty-four people. In contrast to criminal proceedings, which had stringent requirements, coroner juries were made up of shopkeepers, artisans, and others.

These courts faced extreme difficulties when determining whether a mother had killed their neonatal child. In cases of infanticide, they had to determine whether the baby was alive, whether its death was natural, and who may have killed them. Moreover, coroner’s juries were tasked with being convinced beyond a reasonable doubt that a murder had occurred before issuing a homicide verdict.

The first difficulty was that others rarely witnessed these murders. These homicides could be carried out in total privacy, leaving no one to testify.

Another potential problem was that the victim needed to have been alive for their murder to be considered homicide. For these Victorians, it was difficult to determine whether the child had been alive, especially if the victim’s body had been concealed. In this context, babies were not considered to be alive until they were entirely outside; thus, a baby that was not wholly born could not be killed, even if it were strangled3.

Jury composition was a third complication because these were made up of local men whose decision-making was complicated by their feelings towards the suspect. Did they bear sympathy or hostility towards the accused?

Murderous Mother?

In 1857, Elizabeth Wigginton (41 years old) was investigated for infanticide in Glinton. She had four legitimate children and had been recently widowed. Wigginton ran a 200-acre farm and was part of a well-connected family. She was a secret alcoholic and addicted to opium. In late April 1857, she locked herself in a room with booze and locked her newborn in a cabinet. She had not told anyone about the pregnancy. Eventually, one of her daughters found the deceased baby, and a Doctor was called. Later, when questioned, Elizabeth claimed, “It’s all moonshine! There was nothing at all! I do not know why you were sent for.”

Elizabeth’s Inquest

Wigginton’s inquest was held at a pub whose landlord was her brother. Glinton had a population of about four hundred people. The proceedings were unusual for two events: first, Elizabeth did not speak, and secondly, her servants did. One of her servants said she realised Elizabeth was pregnant, but had not discussed it. During the inquest, the doctor claimed that the child was born prematurely and had been strangled; however, he did not discuss whether the baby was born alive.

Despite this question being unanswered, she was held responsible partly because she had concealed the baby’s birth. Her case was unusual because locals knew she was an alcoholic and thought that if she had been sober, she could have perhaps successfully hidden the baby. The jury implied she should know better. Her substance abuse and sexual activity were not aligned with her role and social class.

Michell’s investigation into Victorian England

This historical investigation of infanticide in Victorian England reveals that

Science and medicine played a significant role in determining whether babies were alive and, hence, whether homicide was a possibility.

Local ideas about gender and social class affected coroner juries’ judgments.

Inquests were not necessarily more lenient with mothers who had allegedly murdered their children; instead, such cases were especially challenging.

Justice is not so blind as she is painted, Gender-based leniency in Welsh homicide trials, 1850-1900 by Stephanie Brown at U Hull

Did a perpetrator’s gender affect courtroom proceedings during Welsh homicide trials between 1850 and 1900? Stephanie Brown concludes that gender’s role during these proceedings has been exaggerated.

Brown’s investigation challenges the historiographical record, which states that women accused of murder were treated more leniently both in the courtroom and after trial. These claims often rely on data about executions and are less concerned with innocence and guilt. Rather than exploring whether sentences were commuted, Brown sought to enter the courtroom and investigate whether there was systematic leniency towards female defendants during their proceedings. Thus, she looked at criminal registers (1837-1892) across Welsh counties and also examined Welsh Newspapers4.

In her analysis, Brown found that about forty percent of men tried for homicide were found guilty5. In the case of women tried for murder, about 30% were found guilty. During this time, fifty-two women were acquitted, and twelve were killed. If one excludes infanticide, only four women were executed during that time.

In this context, violence was often linked with masculinity, and writers discussed why women kill. Frequently, they concluded that such women must be mad, bad, or sad. In some cases, the defence insisted that a violent woman deserved mercy because their hormones made them do it. However, in many instances, like the one about two women who killed a servant, the media narrative and court documents do not show much consideration of their gender.

The discourse about some women accused of murder is that they are bad. For example, Mary Ann Phillips was described as drunk and violent in Cardiff in 1888. She had often beaten her husband and had previously spent six months in prison for assaulting him. A neighbour is said to have remarked, “Next time it will be the rope.” However, there is no evidence to suggest she was convicted because she was a woman, and not as a result of her husband’s injuries (broken bones and fractured wrists). Nonetheless, the jury did recommend mercy on account of her age (59) and gender. The discourse surrounding other women suspected of murder is that they were acting out of victimhood or sadness.

In other cases, women were exonerated for several reasons. For example, Sara Matthews was accused of murdering her husband. He was found with a head wound, which the police thought was caused by a poker they found. She denied killing him, and the press around the case had not portrayed her as sad or bad. She was found not guilty due to insufficient evidence.

In contrast, Elizabeth Jane Thomas was sentenced to death in 1889. She was found to have killed Agnes Lewis, who had allegedly come to her for an abortion. The press was more focused on the deceased than on Thomas, who denied participating in the abortion.

Brown concludes that gender did not play a significant role in these decisions and that the narratives about these cases were not gendered. Nevertheless, answering whether gender played a role in post-trial decisions was beyond the scope of her work.

Gendered Mercy vs Global Politics

The Home Office in England and Wales reviewed every death sentence for capital murder in 20th-century England and Wales to assess whether mercy was warranted. They decide to imprison rather than hang 640 out of 1486 individuals. Alexa Neale argues that mercy was “applied secretively and unequally,” and that petitions, judges’ advice, and jury’s recommendations were relatively unimportant despite being explicitly mentioned by these bureaucrats as crucial.

In one case, the Home Office privately placed political concerns above all else, and concurrently gave other public justifications to defend their decision. In 1914, a Portuguese man shot his wife twice while sailing on a British-registered ship. The man was 32, and when taken, claimed he had no memory of shooting his wife. He argued he went mad—a fact a British doctor disputed after examining him.

The jury had to first decide whether this thirty-two-year-old non-English-speaking man was insane. They determined that he was not, and had been sane, and was thus guilty of murder and condemned to be hanged. He was reprieved. At the time, the reasons a person was offered mercy were rarely made public. This lack of transparency makes it hard to unveil the obscure reasons why some people were allowed to live, and why other narratives were allowed to be perpetuated. One of these narratives blamed the victim, as it was argued that the victim did not conform to gender roles, that she was bad, and thus deserved it. In several instances, men murdered their wives. In cases where men murdered their wives, defence lawyers would often invoke failed gender expectations, especially when intersecting with issues of race and citizenship.

In this case, the narrative transformed the victim into a whore. The Portuguese man called her a temptress, claiming she was only interested in his money. Every detail about the case was twisted to make her look bad, to make her behaviour unwifely. The office discovered he was the one with the shoddy sexual past and that he had suffered from syphilis twice. There are letters from 1914 where diplomats racialise this man and the Portuguese people. These also discuss the risk to British diplomats in Brazil and Portugal if this man were executed.

The man’s death sentence caused considerable agitation in Portugal, where capital punishment had been recently banned. Private records show that the Home Office felt they needed Portugal as an ally, and they were concerned about how the Portuguese press was covering the case. In 1916, he was given early release. At that point, and after it was clear, they added political considerations as a reason.

Neal examined their black books, which are key to understanding procedure, precedent, and micro narratives. She found several reasons for interference, including judicial legal reasons, offender demographics, psychological factors, public reactions, and political considerations.

In the case of the Portuguese man, the real reasons remained hidden, allowing other narratives to gain popularity. Such an outcome can perpetuate the idea that murdering women is acceptable, and this case reminds us to pay attention to the context of these narratives: who is telling them and why. Neal also prompts us to consider what is at stake and the legal frameworks with which these narratives interact.

There are other cases where a murderer may have been released, not because the victim was seen as bad, but because there were other considerations. In some of the files, the bureaucrats listed a potential factor, but it was not thoroughly considered. Some of these were used as outward justifications, but privately, these bureaucrats made other considerations.

In the case of the Portuguese murdered, they felt that England needed Portugal as an ally. Some letters mention this alliance. The British office considered that the Portuguese Royals were in England, that the death penalty had been abolished in Portugal, and that if this Portuguese murderer was put to death, the resulting agitation might also endanger British ministers in Portugal. Further, before the ship reached the UK, it made some stops where the man could have been taken and extradited.

In short, Neale’s investigation reveals that the Home Office decided who to grant mercy through varied criteria. Further, she documented significant differences between this office’s public and private justifications for their decisions.

Conclusions

All these cases demonstrate how vital it is to examine history in detail and consider alternative explanations. Historians in training are often warned about “whiggish history,” which is a narrative that reflects a particular purpose. They are also warned of the dangers of presentism, which is when the analysis imposes present concerns or categories into the past. These histories demonstrate that analytical categories can be useful, but also highlight the need to understand history in its own terms.

In particular, Michell and Brown’s research reveals complexities about the past that could be easily overlooked without a thorough investigation. They both made cogent arguments as to why gender was less important than other factors. This is not to say that these societies weren’t patriarchal, but rather that in the context they studied, other factors were more significant.

For our purposes, it is key to note the role played by authorities in determining whether deceased infants had been born alive or not. We were unaware of this distinction and were surprised to learn about it. In these cases, discerning whether a death had been natural was pivotal. Thus, creating a space for experts to play a determinant role in such investigations. This is a possible research area, where a scholar should explore how these determinations were made, who made them, and document the growing authority science and medicine played in these matters.

The world revealed by such histories is more intricate, logical, and alien. These wonderful case studies indicate that the past is as fascinating and sophisticated as the present and that understanding it demands thorough investigation.

Last April I attended the ESSHC conference in Leiden, and saw some great researchers present fascinating work. This post is based on my notes and recollections of those talks1. While I have made a good faith effort to represent these researchers work, I cannot guarantee the fidelity of my notes and I may have inadvertently made mistakes. I am solely responsible for those.

In this sample, two were determined to have died of natural causes, and one death was deemed accidental.

From our vantage point, it is easy to forget a world with high infant mortality rates, and in Victorian England, it was about 15%.

These give a lot of information about trials, and some about inquests.. The Calendar of Prisoners provides very little information beyond the person’s name, age, occupation, the name of their lawyer, and the alleged offence for which they were charged.

Among male defendants, 47 were executed, and 69 were acquitted

Thank you for such a thoughtful write-up (and for coming to a very early panel in the first place!!)