Young Criminals in Berlin: How the Cold War Changed German Criminology

East and West Germany sought to weaponize youth crime by offering accounts that highlighted the superiority of their politico-economic systems.

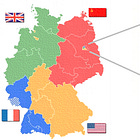

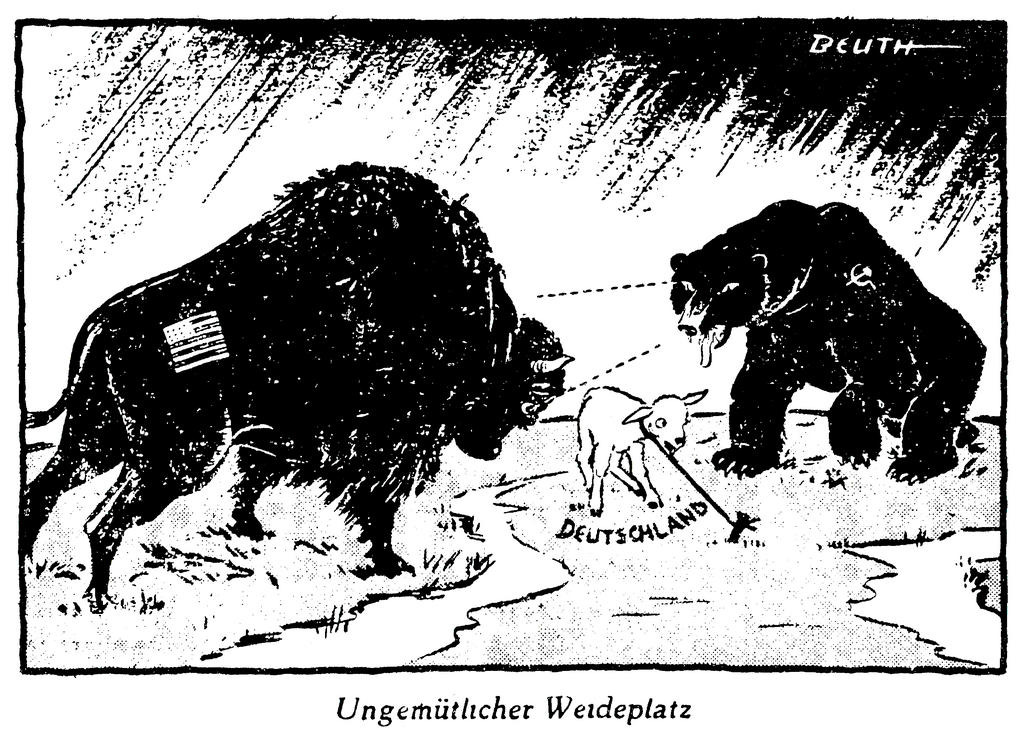

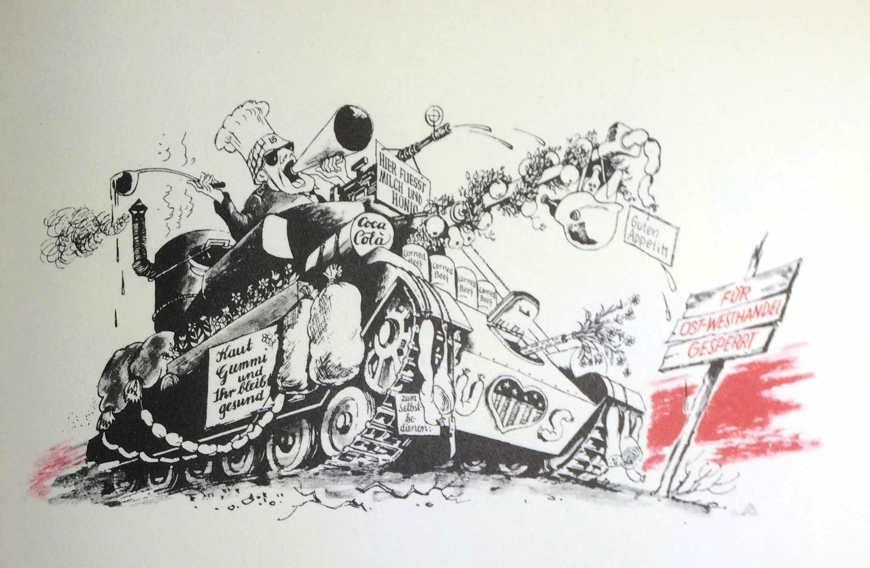

The understanding of youth crime in post-war Germany was drastically influenced by the defeat of Nazi Germany and the challenges it presented (Orlic & Heili, 2024). The future of Berlin was significant because it contrasted the fruits of capitalism with those of socialism, and the world paid attention because Berlin was one of the spots where the Cold War could have gone thermonuclear. After the war, the occupying powers and German criminologists suggested new etiologies of crime which were markedly different from those of the Nazi regime. Rather than relying on biologically deterministic criteria, West and East Germans provided social explanations for why people committed crimes. The shift from a deterministic understanding of criminality to a social one allowed each party to break with the Nazis and provided them with the possibility of finding redemption and, thus, the opportunity to build a brighter future. While thinkers in the East and West were concerned about similar behaviors and phenomena, the explanations they crafted were concordant with their political goals (Evans, 2018). In short, both East and West Germany sought to weaponize youth crime by offering accounts that highlighted the superiority of their politico-economic systems, turning criminology into another Cold War front.

The pervasiveness of the Cold War, which acted like a universal acid, affected many intellectual endeavors such as science, economics, and even criminology. Our world continues to reflect and operate with systems and structures developed within the context of the Cold War. For example, NATO was created as a safeguard against a Soviet invasion. The recent expansion of NATO as a response to Russia’s war on Ukraine is yet another example of the significance of these Cold War structures on the contemporary geopolitical landscape.

The End of Nazi Germany & A New Criminology

In contrast to biologically determined causes during the Weimar and Nazi periods, the people in Berlin had not changed, but the amount of crime continued to increase. Therefore, biological determinants could not fully account for such a dramatic increase in crime. Thus, the only acceptable explanation was that the conditions had pushed people who would otherwise be law-abiding citizens to commit crimes. In this environment, new explanations for why people commit crimes would heavily focus on environmental/situational causes. Despite alluding to similar causal factors, the East and West used their explanations of an increase in post-war crime to highlight their differences. Both alluded to social factors, invoking the scarcity of essential resources (such as food), broken families, and a lack of education (Evans, 2018).

As the relationship between the US and the Soviets soured, it became vital to improve the situation in Germany. The initial actions taken by the Soviets and the Americans worsened the conditions in post-war Germany. In turn, there was an increase in criminality and youth crime in Germany. From the very start of the occupation of Germany, the explanations offered by the East and the West highlighted the differences between their socio-political systems. This early distinction suggests that these differences are at least partly rooted in using different frameworks to devise solutions to the challenges they faced rather than being mere propaganda. Nevertheless, each side grounded its analysis on factors that allowed it to condemn the other.

This so view of crime and the actions people took also opened the door for Germans to redeem themselves because these criminal acts reflected their situation rather than themselves. Across Germany, it was said that “economic misery and a lack of food and consumer goods are the driving forces behind women’s attempts to improve their living conditions through sexual favors (Heller, 19419).” Thinkers often invoked the broken family to explain the increase in youth crime because they thought children had no one to guide them (Evans, 2018). For example, in Aachen, there was also an increase in crime, and this was connected to the scarcity of food and the loss of parental authority (as some men had died in the war, others had been arrested or separated) (SSA, 1947). This concern about the family would persist, and in 1959, the Ministry of Family Affairs, Wuermeling, called for mothers to stay at home to help raise proper children and instruct them in “ethical values” (Wuermeling, 1963). The West and East agreed on the factors but traced their genealogy to different causes.

Same Causes Different Meanings

At first, the East and the West explained crime, and more specifically, youth crime, by alluding to the same factors (war conditions, broken families, lack of resources). Nevertheless, the Soviet influence on Eastern explanations led them to link these conditions to capitalism, whereas, in the West, they were seen as resulting from the war.

In the early 1950s, the etiology of crime diverged further. The East sought to explain criminal behavior and problematic youth behavior in ways that allowed it to highlight the differences between communism and capitalism. They claimed that the root causes of such antisocial behaviors were inherent to capitalism and thus demonstrated the superiority of their system. They weaponized their narratives about youth crime to argue that their system was superior.

In the West, commentators linked undesirable behavior in the East to poor conditions. However, when discussing problems within their zones, they identified social factors that were present in Western Germany. While these commentators did not blame the East, the factors they often identified as important were ones that were a) not inherent to capitalism, b) would be even worse in the socialist East, and c) could be solved within their current framework. While these narratives were not directly aimed at the East, they implicitly suggested that the West was better equipped to solve social issues.

The Wall

The Berlin Wall further cemented the differences between East and West Germany. As a result, it changed the way each side understood crime. The views and practices that developed during the postwar years became entrenched and continued to challenge criminologists as well as East and West Germans, who tried to curtail crime and undesired behaviors. In West Germany, the criminal code remained unchanged even after an effort to reform it in 1969 (Heiland, 1992). East German authorities shift the focus of their codes in relation to how crimes affect the people’s State (Reuter, 1992).

Socio-structural Causes and Crime in West Germany

The use of social explanations for crime that developed in the post-war years would persist for decades. For example, during the economic crisis of 1966-67, the increase in crime in West Germany was linked to “social destabilization” (Heiland, 1992). In 1978, another wave of growth in crime was attributed to young immigrants, even after a study found them less likely to engage in criminal behavior except for those aged between fourteen and eighteen (Gross, 1978). In this instance, Western German criminologists argued that the lack of opportunities and integration drove these young people to commit crimes (Gross, 1978). These thinkers, like the early commentators in West Germany, said that the blame partly rested on German actions. The structural issue this time was a law that made it harder for the children of immigrants to find apprenticeships (Gross, 1978).

Conclusions

The weaponization of narratives about youth crime is an instance in which the Cold War affected the intellectual development of ideas and policies. This history continues to shape the lives of everyday Germans. The East used their explanations of crime to suggest that capitalism created bad people with poor behaviors. In the West, there was a focus on social factors that highlighted the difference between their sociopolitical systems. Both alluded to social factors, invoking the scarcity of essential resources (such as food), broken families, and a lack of education. Throughout our articles on youth crime in post-war Berlin, we have proposed seeing distinct criminological narratives as another front on which the Cold War was fought. We think that ideological commitments shaped how historical actors interpreted phenomena and that disputes about cause and effect were intentionally (and unintentionally) weaponized in an effort to demonstrate the superiority of their socio-political systems. In this way, we hope to offer a prism to study the Cold War era.

This post heavily draws from an essay Christian wrote for a class on the history of everyday life in Cold War Berlin. Christian would like to express his gratitude to Briana and Caroline for an exciting course, their help and support. Lucas and Christian have worked on a substantial revision of Christian’s original work.

A discussion of how East German Criminologists Claimed Capitalism made people worse

East German Criminology Linked Fascism, Capitalism, and Crime

The terrible condition in which Berlin found itself after the war

Ideas about Crime in Weimar Germany and Nazi Germany

West German Criminologists Claimed Social and Structural factors drove young Germans to commit crimes. These factors were not linked to capitalism and would be even worse under socialist regimes.

Weimar Germany and Nazi Germany developed a criminology that was largely biologically determined.