The Seed Program

"The Seed indeed is all you need / To Stay of off the junk and the pills and the weed"

The Seed Inc., was one of the pioneer Troubled Teen treatment centers. They instituted a program that they claimed succeeded in over 90% of the cases. The program was perceived to be legitimate because it drew from contemporary thinking in psychiatry, psychology, and prevention science* and thus was aligned with contemporary thinking. The Seed incorporated techniques and technologies to radically change the behaviors of those committed to their care. These approaches predate Synanon and suggest that the origins of the Troubled Teen Industry are deeper. This week’s article presents a coherent description of the Seed’s Program despite discrepancies between official and survivor accounts.

The program was divided into three phases, and transgressions could get a Seedling started over at any time (Polonsky, 2005). To be started over, meant to start the program from scratch. These phases utilized different technologies that allegedly made them successful. The program’s key features were the use of rap sessions, the isolation of individuals under their care via the use of foster homes, and their staff. The Seed sought a total reformation of the social milieu of those they treated and was somewhat open about its practices.

The Seed used sleep deprivation and hunger throughout its program to increase pressure on those under its care so it could more easily change their attitudes and behaviors. During an interview with G, a former Seedling, she said, “we were never allowed to get enough sleep” (Ginger, 2024). According to another former Seedling, newcomers got four or five hours of sleep a night. Seedlings claim they were insufficiently fed, and their diet solely consisted of baloney cheese or peanut butter sandwiches, Kool-Aid for lunch, and sloppy joes or chow mein for dinner (Ginger, 2024; Polonsky, 2005; Eskoff, 1973). Often, families would be asked to make sandwiches that were kept sitting around for days; before being offered to those in the program (Polonsky, 2005)*. Seedlings rarely got enough food to feel full.

The First Phase: Breaking You Down

The first phase, which usually lasted two weeks, used supposedly legitimate interventions which were thought effective at changing behavior. During this phase, the focus was on isolating individuals from the environment in which their problems had developed. The other main goal was to supervise newcomers who were never alone. They were introduced into the program through twelve-hour daily discussion sessions known as raps (SDAP, 1972; Polonsky, 2005). A pair of professional mental health sciences said that these sessions were “carefully guided,” but Seedling accounts paint a grimmer picture (Hardy & Cull, 1973).

The Seed called those under its care Seedlings. We recognize that this terminology is problematic, but we have chosen to utilize it because it more accurately conveys both the program and the assumptions of those who designed, promoted, and completed it.

The Seed also sought to control how people dressed. According to G, the Seed required boys to have short hair and no facial hair and prohibited people from wearing concert t-shirts, ripped jeans, flip-flops, and cutoffs. Cult scholar Daniella Mestyanek Young argued that controlling dress is one strategy cults utilize to create an aura of ever-present control, a reminder of who is in charge (2022; Young, 2024).

During the first phase, newcomers would be assigned to foster homes where they would stay with an Oldtimer, thus providing 24-hour supervision over them (Hardy & Cull, 1973). According to former Seedlings, these accommodations would be prison-like and have locked doors, guarded windows, bathrooms without doors, and complete control over food intake (Defoor ; Polonsky, 2005; Ginger, 2024).

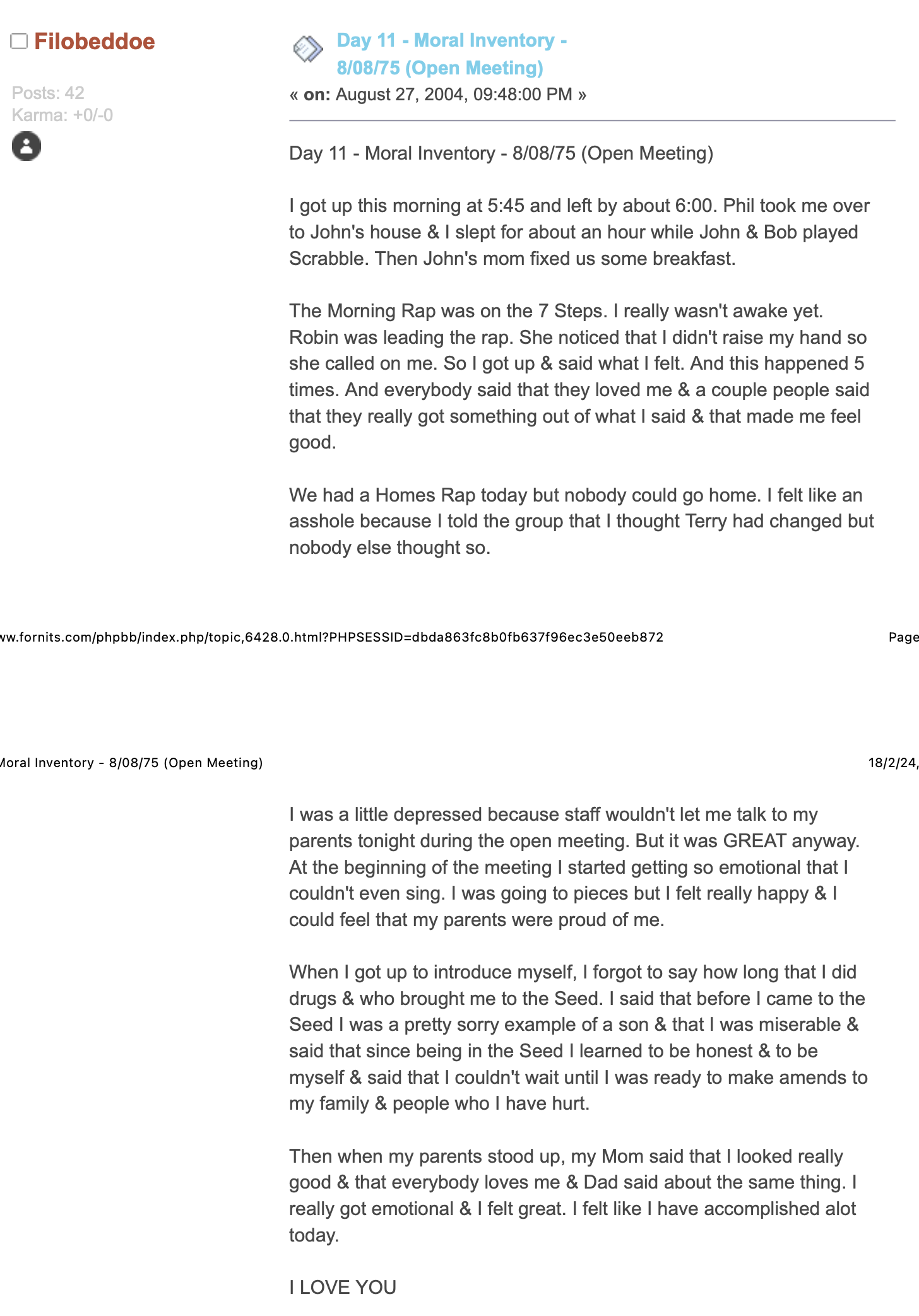

Each night, Seedlings presented moral inventories to their assigned oldtimer, who had to approve them before newcomers were allowed to sleep. These inventories asked them to reflect on what they had done well and explain the reasons behind what they had done poorly.

During this phase, newcomers were only allowed to speak to staff and oldtimers. Any kind of communication with another newcomer, family, former friends, or acquaintances was harshly punished (Polonsky, 2005). Steve Deffoor wrote that Seedlings:

“could not socialize, as indeed no one could. No one could talk to another individually while at the Seed, and no clique’ing was allowed.”

Moreover, Seedlings were coerced to condemn their previous friendships because these were said to have been “bullshit”: merely a means to abuse drugs (Polonsky, 2005). In one Seedling’s moral inventory, we learn that he declared in front of his parents and the entire group that he had been a “pretty sorry example of a son.” (Filobeddoe, 1975) These inventories had to include “the date, your number of days on each phase, and then your total number of days… there is a challenge to say something bad about yourself that you want to fix. Write about how you are going to fix it… say something about how the program has improved your life” (G, 2024). Thus, newcomers were effectively isolated from their previous lives, sleep-deprived, starved, and overwhelmed. These conditions were thought to make individuals amenable to having their personality changed.

The shock of isolation, hunger, and sleep deprivation was an effort to push Seedlings to adopt the Seed’s philosophy. Whenever a newcomer complained or questioned something, they would be told that they were “full of shit.” (Polonsky, 2005) Polonsky remembers being told by his oldtimer, “Your attitude sucks. Listen. Don’t argue with me. Your attitude sucks.” (2005). The program aimed to persuade the newly inducted that their life had been “characterized by dishonor, dishonesty, pettiness, insecurity, and meanness.”*** Thus, further rupturing these individuals’ relationship with their previous life. Often, oldtimers would tell newcomers they loved them too much to let them fail. Furthermore, the program would break people and cause distress. A former Seedling, claimed that because of the Seed program, he was no longer able to form emotional relationships and often contemplated suicide.**

Seedlings were moved up to the second phase after completing the first phase. Significantly, this promotion was based on meeting certain criteria and not on time spent at the program. Therefore, individuals are forced to participate in their transformation.

Phase 2: Free to Behave

Scholarship at the time suggested that total control over an individual’s environment was the best way to modify their attitudes and behaviors. The total control that the Seed aimed to have over those under its care continued during the second phase. This phase usually lasted three months and required Seedlings to participate in four rap sessions per week (Hardy & Cull, 1973). Further, Seedlings were required to ask permission before going to the movies or engaging in other social activities. This was usually granted if other Seedlings of the same sex were participating (Polonsky, 2005).

Seedlings could leave their foster homes and return to their own by this time. Despite returning home and to their former lives, Seedlings were instructed to only interact with other Seedlings at school and in their communities. The Seed sought to enforce this rule by relying on Seedlings to spy and inform on one another. This way, any transgressions beyond the direct view of the Seed could be addressed (Polonsky, 2005). Perhaps surprisingly, this worked well because they feared being started over. As a result, individuals continued to be isolated even if they had returned to their homes, their schools, and their communities. Seedlings could be punished for transgressions and for failure to report them.

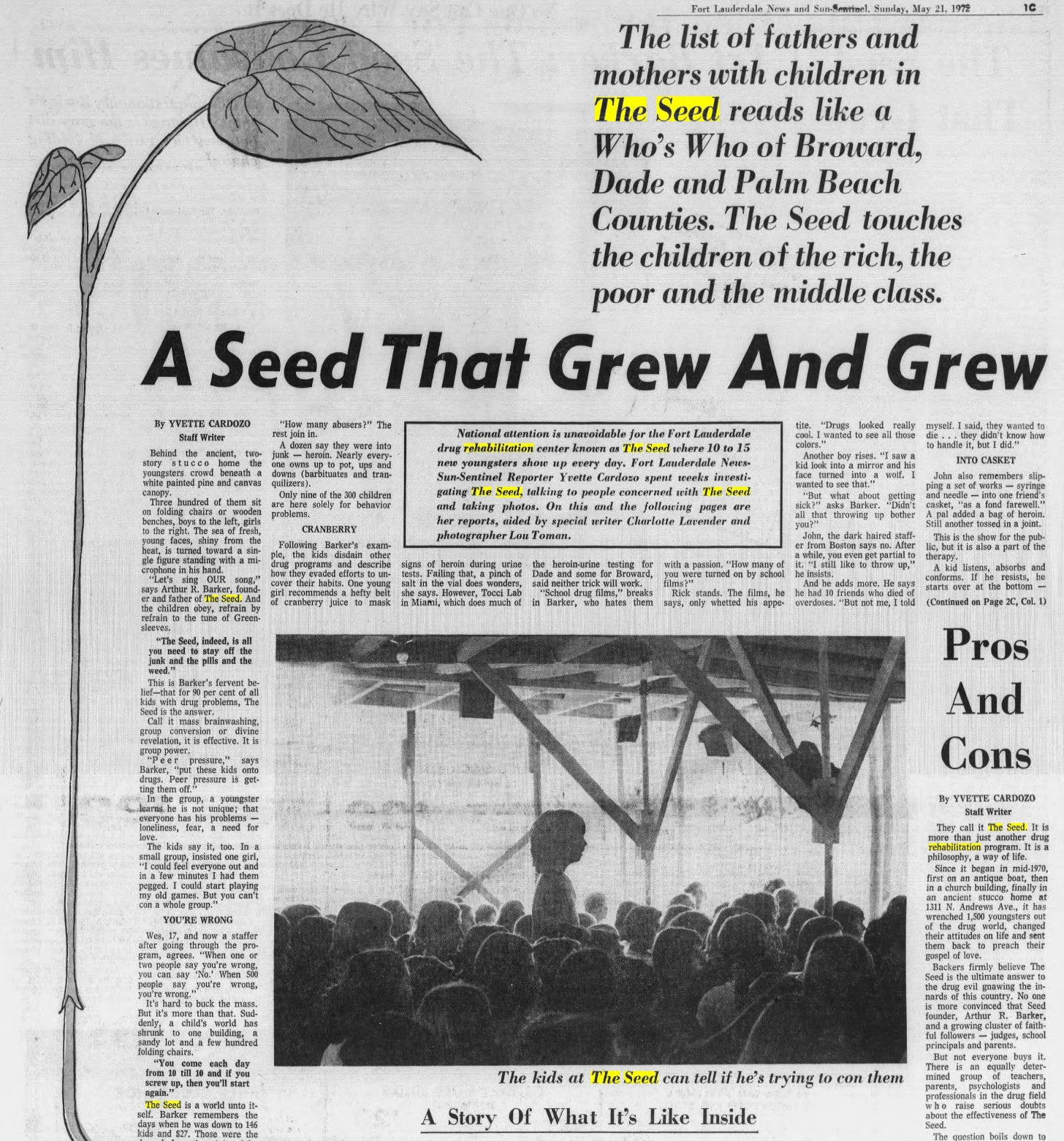

Several commentators were impressed at how well this system of informants worked. The program noticeably changed those who were enrolled in it. Helene Kloth said that Seed graduates appear “straight” and are “quiet, well-dressed, short-hair, and not under the influence of drugs” (Miller, 1973). Upon completing this phase, Seedlings were straight but told they had to attend meetings once or twice a week.

RAP Sessions

The rap sessions were both the mechanism by which the Seed claimed it could turn troubled young men into healthy, desirable citizens and one of the reasons the program appeared legitimate. These sessions were meant to change Seedlings ’attitudes and dealt with subjects such as “love, happiness, games, friends, three steps, seven steps, conning, analyzing and justifying, and honesty” (Polonsky, 2005). Usually, about 300 people participated in these sessions, and they were segregated by sex (Polonsky, 2005; Eskoff, 1973). Everyone in the program had to attend these.

These sessions used formal and informal peer pressure. They often consisted of confrontational therapy, where the staff and their peers verbally attacked individuals until they broke down. The rap leader would make comments, and the audience members appeared eager to raise their hands to participate. This eagerness often shocked newcomers, but they quickly realized that people who did not were accused of “copping out” (Polonsky, 2005) The staff singled-out individual was said to be stood-up, and the group mercilessly attacked them. Then, when they confessed how terrible they were, others would say they loved them. This was often referred to as positive peer pressure, and its use was frequently praised. To end the rap sessions, Seedlings would “put their arms around the shoulders of the two people next to them and sang with great gusto” and then recite the Lord’s Prayer.

I (@Christian) spoke to G, a former Seedling. She told me about rap sessions and the Seed. She shared one memory with me when she was “coming into group from school one time, and there was this one guy” who was “being stood up and confronted. And he was snot crying, balling his eyes out, and begging to be sent back to Rayford” (Ginger, 2024). This guy was the son of someone high in Florida corrections, and the rumor was that “his dad pulled some strings to get him deferred into the program” (Ginger, 2024). This guy had done time at Rayford, a “notoriously hard prison in Florida; it is where the baddies go” (Ginger, 2024). He had been sent to an oldtimers home that used barbed wire and Dobermans to control the kids therein. Years later, Ginger would learn why that guy was confronted. Before she arrived, a 14-year-old “little boy” who was sent to the same house shared with the group. This boy had been sent to that house because he had tried running away from other houses.

“This little boy got stood up and confronted in a rap about why he was bleeding so badly from his anus that it was actually dripping from his chair onto the floor. And it turned out this twenty-one-year-old line backer looking, you know, inmate from Rayford, had been violently raping this kid. Nightly.”

The rapist got started over. He went through the program and became an oldtimer. The Seed then “started sending him home with little boys again” (G, 2024). G befriended this little boy. He passed in December 2020, and it was “intentional,” and he “let it be known” (G, 2024). “He decided to heat his step van using a propane burner with an iron frying pan turned over upside down on top of it. He took a picture of it clearly showing the orange flame” (G, 2024). This person had made a living in the sales and repairs of mobile homes. So he knew damn well.”

Completing the Seed Program

The Seed wanted to convince those under its care that they had been “dishonest, insecure, unkind, thoroughly worthless mess” before the program (Polonsky, 2005). The criteria on which the staff decided whether to promote a Seedling included abstaining from using drugs, but the staff gave greater weight to seeing evidence of an “attitude change toward life; that is, there is love of self and others, community and country, and a sense of dedication to help his fellow men” (Hardy & Cull, 1973). This allowed The Seed to force Seedlings into actively participating in their alleged rehabilitation. The Seed was solely staffed by former addicts. This feature was enthusiastically praised because former drug abusers were thought to understand the culture and values of other users (Hardy & Cull, 1973).

The Seed was unlike any other program because it got an incredibly high level of community involvement. The families were invited to two open evening rap sessions a week. These were, unbeknownst to those in attendance, toned-down versions of other rap meetings (Hardy & Cull, 1973). These families collaborated with the program in several ways and provided professional services (i.e., legal), drove Seedlings from their foster homes to the institution, made sandwiches to be eaten by Seedlings during the day, fostered newcomers, and more. Two academics said that this level of participation by families produced “remarkable results” which included a “greater level of love and compassion” (Hardy & Cull, 1973). The focus on involving the community is another prominent feature in prevention science, which often ascribes the origins of social problems to the environment around the individual behaving improperly.

The Seed ambitiously sought to solve a social problem by radically altering a young person’s environment so that they could be broken up and put back together into a different person. Barker was incredibly ambitious and thought that the Seed would revolutionize the world. The organization argued they were “unique” given their use of the community for “assistance and support” (Anon, 1974). Barker thought this program could transform the world by getting people “helping themselves and others” (Anon, 1974). Their belief was that it would become the “primary source of enlightenment” for the “entire world” (Polonsky, 2005). At the time, such grandiose efforts to apply scientific technologies to solve all social crises were seen to be within the realm of possibility.

According to Di Castri, prevention science often assumed that certain unjust societal structures had to change because they were responsible for undesired behaviors (2024). These prevention scientists sought alliances with radical groups because they called for the reformation of social structures (Di Castri, 2024). Similarly, The Seed aimed to completely reformulate an individual’s social connections. Importantly, individuals evaluating the Seed understood its program as being preventative. The Health Planning Committee report claimed to encounter difficulty, in the absence of agreed-upon standards, with how to assess “the advisability, feasibility, validity, success rate, and unit cost of this or any other type of program in the drug abuse rehabilitation and prevention field when the field is so new” (HPC report).

Others worried about these technologies, even if they appeared efficacious. The same counselor who said Seedlings appeared straight claimed she no longer supported the program because graduates lived “in a robot-like atmosphere, and they won’t speak to anyone outside their own group.” She no longer thought Seed was “the saving program” (Miller, 1973) She doubted whether their new way of being was “an improvement over their previous condition of being on drugs” (Miller, 1973). Other teachers expressed similar concerns (Miller, 1973). Some Floridians became disgruntled by the Seed’s dismissal of other professionals and institutions. The Seed often told parents to eschew other mental health professionals because they would fail. For example, in a letter to the Governor, a disgruntled parent complained about this. Mabel Wade reported that Barker said these kids did not need “any Medical Men with their Degrees” (Delaney). These apprehensions about the Seed were part of a larger conversation regarding brainwashing and the abuse of technologies, which were thought to soon be able to effectively modify behavior.

1974 Report: Communist Brainwashing Techniques

In 1974, a select committee of the US Congress issued a report on The Federal Role in Behavior Modification amidst national concern about the possibility of refashioning people through technology. This report dealt a blow to the Seed by comparing its methods to those experienced by American soldiers while held captive in North Korean prison camps. Consequently, the Seed halted plans to expand and withdrew grant applications because they would require them to inform parents the program was experimental (Parker, 2011). Even before this devastating report, The Seed garnered a lot of attention, and it was embroiled in controversy regarding its licensing and program. There were several Governmental reports about the Seed. Among these a Grand Jury Report from 1972, the Health Planning Council Evaluation of 1972, and the 1974 Addiction, Consultation, and Evaluation (ACE) Report. The Seed operated despite circumventing several regulatory requirements. Despite the many criticisms and the program being recognized as harsh, the Seed not only flourished but unleashed a series of treatment centers that continue to employ similar interventions.

The Seed succeeded because the technologies that comprised its program were developed by professionals and hence were perceived to be credible. After describing the Seed program, this paper explores the context in which these technologies became powerful and legitimate. We will explore this context in a future article.

We are interested in speaking to other Seedlings. If you were at the Seed and are willing to have a conversation about your experiences please email us at: curingcrime@icloud.com

Sources

*We wrongly attributed a claim that mold had been found on sandwiches to Polonsky. This was said by another Seedling. Polonsky described the food as iky and old.

**Had been wrongly attributed to Polonsky.

***Had been wrong attributed to Polonsky.