The Clockwork Orange: Forcing Dishonest Men to be Good

“What does God want? Does God want goodness or the choice of goodness? Is a man who chooses the bad perhaps in some way better than a man who has the good imposed upon him?” (A. Burgess)

The unforgettable story of A Clockwork Orange by Anthony Burgess (1962) addresses the consequences of the medicalisation of crime. The iconic book and subsequent film, which continued to draw attention despite Burgess’s reservations about his novel, depict the crimes and punishment of Alex. He is a 15-year-old boy who loves classical music and violence. The story is often seen as a futuristic dystopia, yet more interestingly reflects anxieties about the State’s possible use of psychiatric tools to coerce, control, and subdue dissenters, criminals, and agitators. Many fans of the film would be surprised to learn that real doctors and scientists who sought to eliminate undesirable behaviors tried interventions similar to those depicted in the novel/film. These real-life authorities saw criminals as “sick” individuals who needed treatment because they thought criminals “cannot entirely [control their] actions”.

In the story, Alex is serving a 15-year prison sentence. The State offers to pardon his sentence by submitting him to the Ludovico technique, which would eliminate his criminal tendencies and predisposition to violence. This treatment provides some of the most shocking imagery in the film. Alex is strapped to a chair, with his eyelids being forcibly open, so he must watch a series of films showing instances of violence, blood, sexual abuse, and gore while he is being injected with a serum that causes him to feel sick. When Alex objects, the medical professionals assure him that “you are being made sane; you are being made healthy” (Burgess, 1962). The treatment works as intended and Alex is left with a visceral rejection of violence, crime, and sex. Despite some problematic side effects, the treatment cured Alex of his “criminal instincts in a fortnight” and turned him into “a good law-fearing citizen”. Nearly a decade after the publication of the book; similar techniques were allegedly still being used in American psychiatric hospitals.

Note: These historical actors used explicit terminology which can be deeply offensive and disturbing to modern eyes which we cite to demonstrate their assumptions and views.

Abusing Medicine

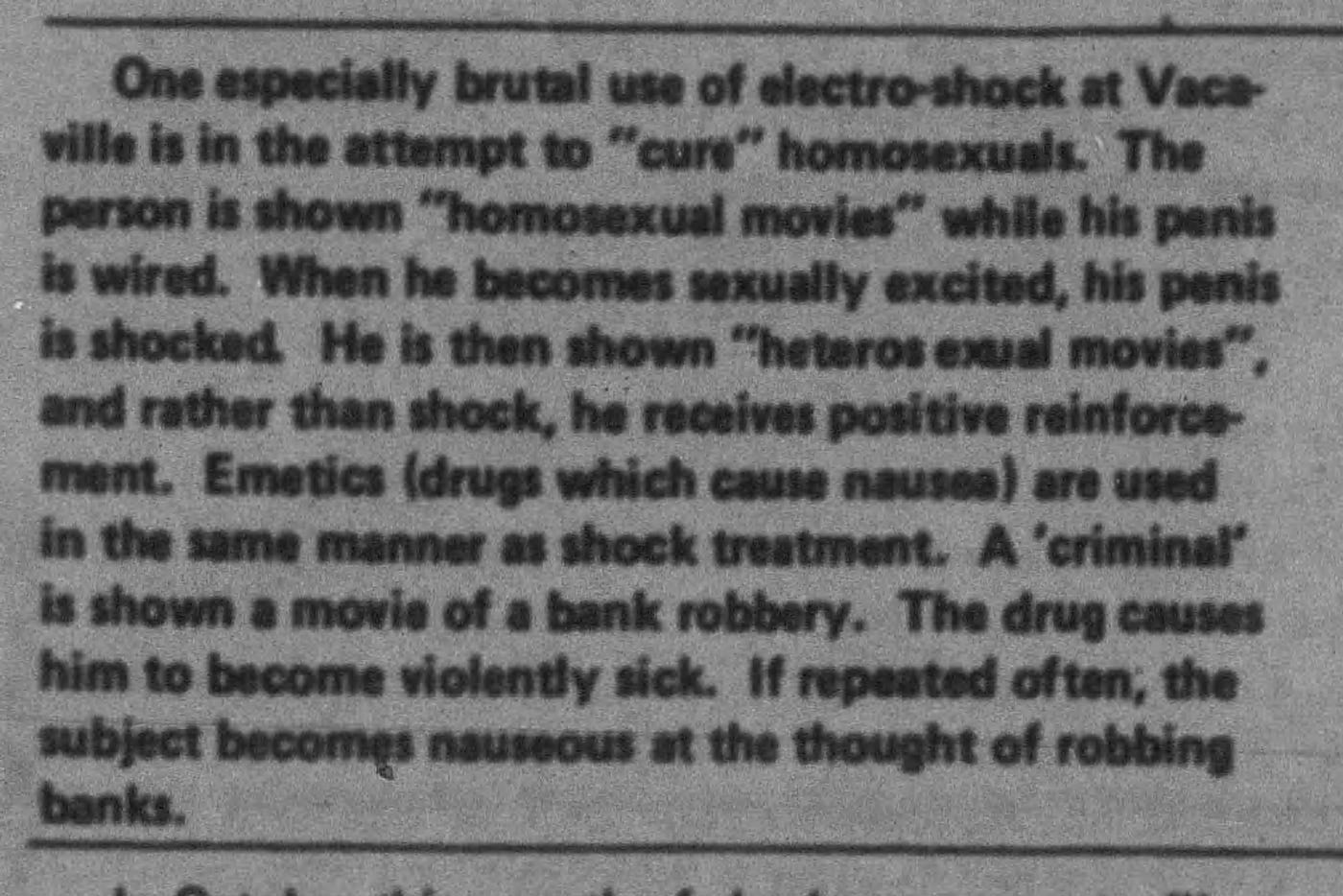

Hospitals across several states tried treating prisoners to eliminate their criminal proclivities. Convicted child molesters were shown “slides of young children and given harsh electric shocks” in prisons in Connecticut and Wyoming (Mandel, 1975). In yet another case, a reporter claimed that Vacaville Hospital was trying to cure homosexuality :

A Clockwork Orange depicts a world where science and medicine are used to rehabilitate criminals. Modern audiences see the Ludovico technique as implausible, abusive, and dystopic; however, efforts to apply science to make “honest men” out of criminals were attempted. This approach sought to do “what a prison cell could not do”. The promise of eliminating criminal impulses through psychosurgery captivated the imagination of doctors, lawyers, judges, and even some criminals who requested these surgeries. In 1947, a habitual criminal called Millard Wright, successfully argued in court for a lobotomy to “kill his uncontrollable urge to break into homes and steal’’. At the time lobotomies were commonly prescribed and seen as legitimate forms of treatment. Scientists felt that they could control impulses through interventions in the brain. For example, José Delgado could stop a raging bull from charging him. Scientists, psychiatrists, judges, policy makers, and others genuinely believed that mind control was a matter of time.

Such was the zeal for these interventions that Wright was released from prison after undergoing a lobotomy which was thought to have changed him into a law-abiding citizen. Other prisoners, like forger Frank Di Cicco also requested a lobotomy in 1952. Di Cicco said he wanted the surgery to “rid himself of criminal traits”. By the time A Clockwork Orange was written, attempts to curb criminality through prefrontal lobotomy had mostly ended in failure. Nevertheless, as the novel implies, enthusiasm to cure criminality through medico-scientific interventions persisted.

Between the early lobotomies and the publication of A Clockwork Orange, there were many significant changes and alleged advances in psychosurgery. In fact, it is debatable whether these interventions should still be referred to as lobotomies. In 1976, a newspaper article claimed that the rehabilitation of criminals could also be done through surgery. These surgeries only destroyed a “tiny, specific part of the brain, in this case the part controlling aggression” in contrast to lobotomies which “left the patient little better than a vegetable, unable to function in normal society”. Despite the shortcomings of early interventions there was widespread optimism that scientifico-medical techniques could be improved so that criminality could be reduced.

In both reality and fiction, state actors, scientists, and doctors responded to what they saw as a social crisis. The apparent increase in crime and the overcrowding of prisons and mental wards coupled with zealous professionals created an environment where new therapies and approaches were used. Alex, Wright, DiCicco, and others were seen as habitual criminals, they were arrested for several crimes. All of them encountered experimental medical interventions to eliminate their criminal tendencies which they decided to try. The Ludovico technique made Alex hate classical music depriving him of one of his greatest joys. Wright’s lobotomy did not cure his criminal tendencies, and ruined his ability to play chess effectively. Both attempted suicided. Wright succeeded. Both chose to participate in a program which involved the use of techniques by which the State could subdue and control its citizens. Both unwittingly sacrificed key parts of themselves.

The Dangers of Medicalising Crime

The development and use of these technologies raises questions which we should all ponder. A journalist writing on the use of these interventions suggested that there is an “element of blackmail” but that “perhaps this is an instance where the individual’s rights are secondary to the rights of society which must be protected from his actions”. Another journalist, in 1976, described these people as “dangerous. Violent” and likely to “attack another human being with the intent to kill”. Moreover, in 1977 the CIA publicly admitted that it had experimented with mind controlling methods including the use of drugs and lobotomy. In contrast Sanchez, a journalist, suggested the advent of these techniques was a “new kind of warfare and dehumanization” that inflicted “terror” on people who were imprisoned. There are many other instances where scientifico-medical approaches have been tried.

In reality and in fiction people who had committed crimes chose to undergo medical treatments designed to eliminate their criminal instincts so that their prison sentences would be either reduced or forgiven. Their choice can hardly be said to be free or informed. A Clockwork Orange is a good place to start thinking about the implications, the potential for abuse, and the consequences of medicalising crime for both individuals and society.

Authors: Christian Orlic and Lucas Heili. This story was originally published on Medium on January 28th, 2023 and imported here on April 15th, 2023.

We have added subtitles to help organize the article.