Terror Threats Alert

Considering the Implications of Anti-Terror Alerts

On October 29th, 2024, Valencia, in Southern Spain, was hit with severe storms that resulted in massive flooding. Official figures state that as of Nov 19th, 227 people died, and close to 10 remain missing. In the following days, a severe weather warning was issued for Barcelona (where we live). Some areas flooded; in others, it was merely rainy. It seems lives could have been saved in Valencia had an alert been issued in time. This got us thinking about weather alerts and terror alerts, and alerts in general. Are these alerts even working?

This week, we looked into anti-terror alert systems in several countries. These are well-intentioned efforts, but we are unsure whether they will help everyday citizens and nation-states. We will briefly describe them and then raise some pertinent discussion points. Let us know what you think!

Spain

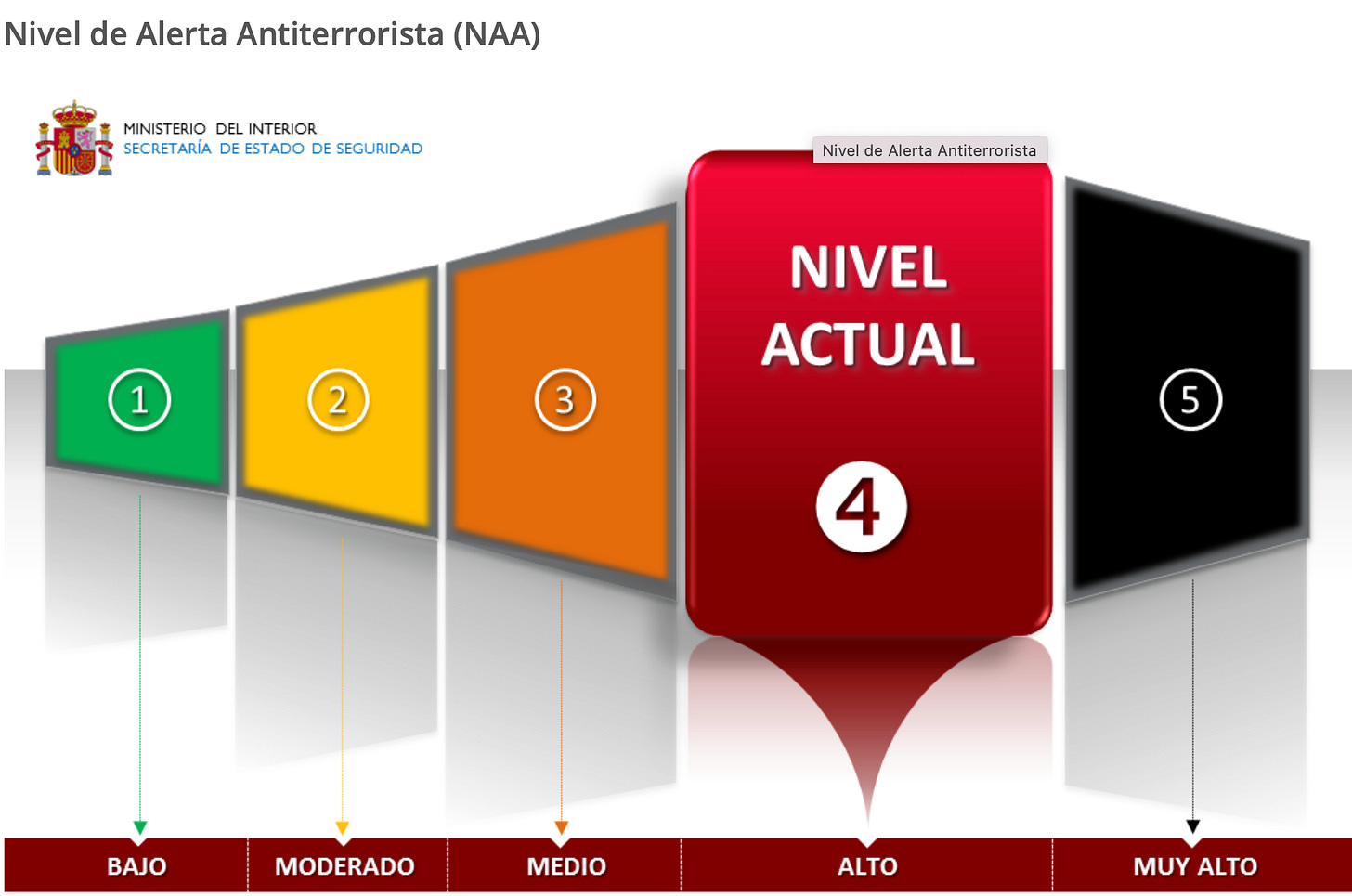

We live in Spain, and like many other countries, it has a terror attack alert system. We were surprised to learn that Spain remains at a “High,” the second highest level.

Barcelona is a beautiful city adorned with marvelous architecture, delicious food, and an enchanting energy. Other than pickpockets, life in Barcelona feels and appears fairly safe. The occasional drunkard can indeed be disruptive, and the eager football fan can be loud, but in general, it is secure. We have both lived in other cities around the world where there is a considerable amount of crime and where robberies can be violent. In comparison, while pickpocketing can be a hassle, it is more tolerable than violent mugging. The city feels safe despite the victims and suffering caused by the attacks of August 2017. We both recognize that Barcelona could conceivably be a target given its symbolic architecture, multiculturalism, and the onslaught of tourism. Most people we know were unaware that Spain remained at “high risk” for terrorist attacks.

In Spain, the “Nivel de Alerta Antiterrorista” (Anti Terrorist Alert Level) is administered by the Ministry of the Interior. This system was introduced in response to the Madrid attacks of 2004. When it was first introduced, it consisted of three levels, but as of 2015, it has five. The official website tracks changes in their assessment. Since 2015, when the five-tier system was introduced, the alert level has remained at “high” (level 4). Some say that if changed to a level 5 then the military would be deployed into the streets.

United States

Currently, the National Terrorism Advisory System aims to provide Americans with “timely and detailed” information regarding terror threats. This system replaced the color-coded threat levels of the Homeland Security Advisory System (HSAS), which was created in response to the terrorist attacks of September 11th, 2001.

In March 2002, President George W. Bush issued Homeland Security Presidential Directive-3, which created a system of alert levels corresponding to a series of protective measures. This system had five alert levels, including the probability of an attack and its “gravity.” The Attorney General was responsible for determining the risk level and deciding whether to communicate changes to the public. This authority was then transferred to DHS. Their assessment was meant to include the credibility of a threat, whether there was corroborating information, whether the attack was imminent, and its potential consequences. The document described some changes that were meant to occur at each level. For example, at the highest level, officials could close public buildings and government facilities. The Bush administration moved the alert levels several times, but the lowest two levels were never used.

In 2011, Janet Napolitano, President Barack Obama’s Secretary of Homeland Security, announced the end of this system as it offered little practical information. The HSAS system had no criteria to determine threat levels. Moreover, changes were rarely explained, and some critics argued that they had been shifted for political rather than security reasons. Napolitano said it would be replaced by a better system in which alerts were specific and included end dates. Thus, alerts would be targeted to specific locations and times.

Other Countries

Most countries we surveyed have five alert levels: Spain, New Zealand, Australia, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, and Canada. Whereas others have four levels (Belgium). Notably, Belgium made an effort to distinguish threat levels against “vital infrastructure” and “soft targets,” both of which were estimated to have a “moderate impact.” A subset of nations publishes a log of when threat level alerts were changed. Very few provide citizens with information on how a change in threat level may impact them or if they should change their behavior in response to an increase in threat level. The EU declared the threat level “acute” but does not clarify what this means nor how many levels or categories they use.

Canada has kept their alert level at Medium since 2014. Canada says threat levels “do not require specific responses from the public.” This makes us question the purpose behind these public announcements. In what is likely an attempt to reassure its citizens, Canada also states that changes in level include changes people are unlikely to see. They also mention likely increases in police forces in public places.

Our brief exploration of these systems raises some questions and concerns.

What do these alert systems have in common, and where do they differ?

Most countries with such systems have threat levels with five different categories of threat assessments.

The categories are rarely the same in different nations. Further investigation would be needed, but nations use different criteria to make these determinations, and the levels can mean different things. In places like the EU, efforts to align these systems could be helpful.

Most of these nations are Western, democratized, and developed.

Most nations rarely, if ever, declare the threat to be at the lower end of the spectrum (New Zealand being the exception).

Do anti-terror threat levels inform the public?

Too General: Most of these nations have blanket anti-terror alert systems, even if they have large territories. Imagine an intelligence report suggests an attack is imminent in a city like Barcelona; how does that affect people on the other side of the country? How does it affect people in small villages 30-50 km away?

Lack of Updates: the public is not sufficiently informed about when the government changes from one level to another. Or, in some cases, of the existence of such a system altogether. We believe the public should also be aware of what level it is currently at and what that level entails.

No Guidelines: Nations serious about protecting their citizens would have recommendations correlated to different threat levels. How should everyday people change their everyday lives in response to heightened levels? Should they avoid certain areas, events, or routes? Should they expect extra security?

The European Center for Counterterrorism and Intelligence. Source

Anti-terrorism Alerts and Their Discontents

We think that citizens should notice when threat levels have been heightened. Thus, a “substantial” risk should feel different from a “medium” risk. One can imagine an increased police presence in the streets, further use of checkpoints, and several other measures.

Governments are incentivized to keep the alert levels at a medium to a high level. One can imagine the public relations disaster a government would face if an attack followed the decision to lower the threat level from “high” to “medium.”

Do security procedures at airports and public buildings change when threat levels change?

In that same line of thinking, we wonder, if there are no perceivable changes in the lives of citizens when the threat level is raised, should there be an alert system at all? We do recognize that not having an alert system could come at a high political cost, even if, in reality, these systems are obtuse and ineffective. Should antiterrorism efforts be just another aspect of regular policing and defense?

Greater clarity is needed about changes in government activities and surveillance when alert levels are raised. How do these raised levels affect budget allocations? Does a raised level give the State broader investigative powers? How does a raised threat level affect regular policing and investigative practices? Do state apparatus get the power to supersede regular law and order procedures?

Finally, like the boy who cried wolf, having the alert set high may establish that as the new normal and lead security forces, citizens, and others to disregard imminent alerts.

Dear readers, we are curious to know what you think. Do you find these systems worthwhile? Do you worry how States may overstep in their alleged efforts to prevent possible terrorist attacks?

Honestly, we had not given these levels and alerts much thought before the floods. Weather advisories are usually narrow and specific to areas and time frames, and this specificity could be useful when issuing terror alerts. It is likely that many nation-states have internal guidelines that kick in when threat levels change. We recognize that some of this information may need to be classified. However, the subject of this column relates to the public.

While we are not experts in this subject, we remain unconvinced about the effectiveness of these systems. We would love to hear your opinions.

Details on Each Country:

Australia Probable

Belgium Infrastructure (Possible); Soft target (likely)

Canada Medium

Netherlands Substantial

New Zealand Low

United Kingdom Substantial