Reducing Violent Crimes: Systemic & “Successful” Efforts in Three American Cities

Baltimore, Detroit, and San Antonio Implemented New Programs and Saw a Steep Decline in Violent Crime

According to an article recently published on CNN, violent crime is decreasing in major US cities (violent crime includes murder, rape, aggravated assault, and robberies). Two journalists, Dakin Andone and Emma Tucker, reported that systemic efforts have drastically reduced violent crime in Baltimore, Detroit, and San Antonio. These cities have had some of the largest crime problems in the country. We will dive into each of these cities and briefly explore their approaches.

Recently, the US has seen the “largest decline in decades” in violent crime (Shotstoppers). Across the nation, there was a 3% decline between 2022 and 2023 (Shortstoppers; Levenson; Campbell & Cole). Some areas have seen a much larger decline, with newspapers reporting figures in the mid 70%. In the US, violent crimes are unevenly distributed, that is, most of them occur in a few places. A study found that 127 cities comprising less than 25% of the American population accounts for 50% of violent crime nationwide. Merrick Garland, the Attorney General, called his change “historic” and if the drop in violent crime in 2024 holds, it will be the largest decline in one year ever (Campbell & Cole). It is worth mentioning that this decline followed a post Covid spike in violent crimes. Thus, the Biden administration may see both a large spike and a large reduction in violent crimes. Andone and Tucker argued that systemic changes helped these cities drastically reduce crime.

*Real Time Crime Index tracks crime in real time across cities and states. *

This website allows users to track real time crime data across the US, States, and some cities.

The biggest declines in violent crimes in Detroit, Baltimore, and San Antonio have been linked to systemic changes which treat crime as a public health problem. The systemic changes go beyond “traditional arrest-and-prosecution,” because they provide social services, interventions by trusted members of the community, and federal funds (Andone & Ticker). There have been efforts to create programs following this approach since at least 1979, when the Centers for Disease Control suggested thinking about “violence as a public health issue” (Detroit). Currently, several of these approaches are funded through Biden’s 2021 American Rescue Plan (Andone & Ticker).

Baltimore: Community, Social Services, and Law Enforcement.

Every year between 2015 and 2021, there were more than 300 homicides in Baltimore (UPENN). Last year, the program in Baltimore allegedly helped lower the homicide rate to its lowest level since 2014. Their approach combined law enforcement, social services, and community.

The Group Violence Reduction Strategy claims its program has driven this reduction. Earlier this year, this initiative helped take down a drug trafficking organization. The GVRS claimed to have “the strongest formal evaluation record of any violence prevention initiative designed to reduce homicides and non-fatal shootings” (GVRS). Their aim is to change the “behavior of groups actively engaged in conflict” (UPENN).

Mayor Scott is the youngest in Baltimore’s history.

In 2022, Mayor Brandon M. Scott changed the GVRS strategy to focus on deterrence. Scott expanded this effort in 2024 and argued that deterrence strategies had previously failed because they lacked proper resources (Scott). Initially, the program targeted the Western District which historically had “highest rates of violence” (UPENN). This initiative attributes most violent crimes to a few individuals (GVRS). The program first identifies individuals at risk, notifies them, and finally, takes action (UPENN). Mayor Scott’s Office claimed that after identifying these individuals, the office offered them “services to help them step away from behaviors associated with violence and are provided a clear mandate from community moral voice partners – residents and faith leaders who leverage their credibility to reach and intervene with people at the highest risk – to put down the guns or face swift, certain, and legitimate accountability through the criminal justice system” (Scott). The group provides stipends for “substance abuse or job placement counseling” to individuals who are identified as likely perpetrators or victims (Andone & Ticker).

This graph shows the 12 month rolling sum of violent crimes in Baltimore.

This program was initiated in some of the most troubled areas and during its first 18 months it was “associated with a 25% reduction in homicides and nonfatal shootings,” a decrease in car jackings, and “no commensurate increase in arrests or displacement of crime to other districts” according to an analysis by University of Pennsylvania's Crime and Justice Policy Lab (Scott; UPENN). Impressively, the data suggests that less than 6% of those the program has treated have recidivated or been revictimized (Scott). An alternative explanation for such a low recidivism rate is that they continuously intervene on false positives (individuals who are identified as possible perpetrators of violence, who would not have engaged in violent behavior).

The GVRS costs about 7.3 million annually (Andone & Ticker). The Mayor’s Office claimed that it has helped 158 people between January 2022 and April 2024 (Scott). This system has issued about six hundred charges against 157 individuals yet only 17% of these charges are violence related (Sonderberg). The UPENN study expressed concern regarding staff being short to successfully deploy the program in other parts of Baltimore. It nevertheless supports this approach because “evidence-based decisions that prioritize both public safety and fiscal responsibility” are key (UPENN). This demonstrates the ways in which science and statistics add a layer of legitimacy and authority to such interventions. There are others who are not as impressed; they argue that this intervention is a mass incarceration by another name (Soderberg).

The program is said to charge individuals as part of a group allegedly engaging in criminal activity. Individuals are offered social services and Mayor Scott declared that if they do not agree, these individuals will face “the full weight of local, state, and federal law enforcement” (Soderberg). Soderberg is also critical that, by charging individuals as parts of groups, they are more likely to accept felony charges even if they were not directly involved in those. Thus, possibly getting non-violent individuals to join the program and lower the rates of recidivism.

Other criticisms include the failure of similar initiatives in the 1990s and 2014 (Soderberg). Charles Ransford, who directed Cure Violence said this program is “just another crackdown” (Soderberg). He also thinks using UPENN’s preliminary report to expand this approach is misguided because it is preliminary. Finally, given the decrease in violent crime across the country it is hard to determine the degree to which this initiative is responsible for the observed reduction. For example, after seeing the largest homicide decline in a decade, Police Officers in Philadelphia said they did not know why it happened (Sonderberg).

Detroit: Localized Solutions to Prevent Violence

Like Baltimore, Detroit has been historically linked to violent crime. Andone and Tucker also argued that systemic changes in Detroit resulted in a significant reduction in violent crime. According to Melinda Clark, Director of the Hudson-Webber Foundation, these approaches are different because they study the “root causes of crime, not just its symptoms [and] take a preventative approach to violence” (Detroit). Note again how medical terminology is being used by those who support these strategies. Similarly to the program in Baltimore, they start with the view that violence begets violence. These individuals are the superspreaders of violence. In Detroit, black people make up 30% of the city’s population and 58% of the prison population which is why many of these interventions are focussed on them (Shortstoppers).

Force Detroit has made a series of recommendations to more effectively curb violent crime and we wanted to share these ones with you.

Proponents of these approaches argue that, previously, these systemic approaches have failed because they lacked funding. Biden’s American Rescue Act provides 700 000 to communities to locally reduce crime among which is Shotstoppers. Deputy Mayor Todd Bettison, who worked with the police department for thirty years, was impressed by how community groups de-escalate violence. In 2023, the most successful of these programs was FORCE DETROIT which saw a 72% drop in homicides and shootings in the period between November and January 2023, as compared to 2022 (Detroit). This group seeks to meet:

“residents' basic physical and psychological needs through access to housing, food, employment or financial security, among other goals” (Andone & Ticker).

Force Detroit is mostly staffed by former perpetrators of violence because these people are considered to be “credible messenger[s]” (Detroit). For example, Dujuan “Zoe” Kennedy serves as Force Detroit's executive deputy director of programs. He joined a gang when he was young and pleaded guilty to manslaughter. He joined Force Detroit after serving time. This background allegedly makes him credible in the eyes of the target population. These credible messengers communicate with possible perpetrators frequently and through phone calls, social media, texts, and in person meetings (Andone & Ticker; shotstoppers). The organization allegedly helps these people stabilize their lives.

Force Detroit is one of several programs operating under a group called Shotstoppers. Shotstoppers is funded through Biden’s American Rescue Plan, has a budget of ten million dollars and it provides organizations with 175 000 grants per quarter. Other groups like Detroit’s Friends and Family, and more, have also accomplished some reduction in violent crime. These organizations report data which readers can explore to evaluate their success.

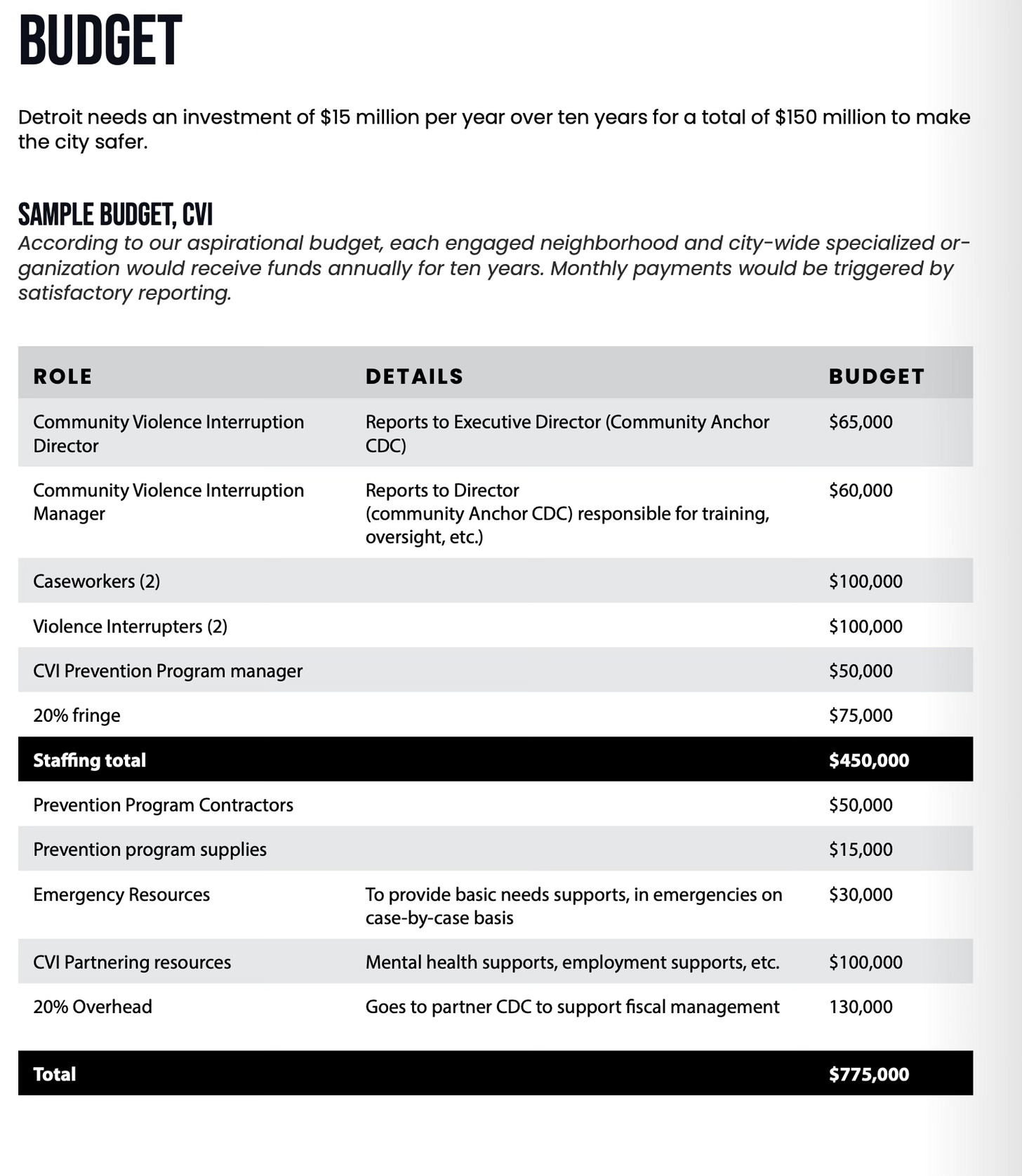

This is a sample budget from an information book found in Force Detroit’s website.

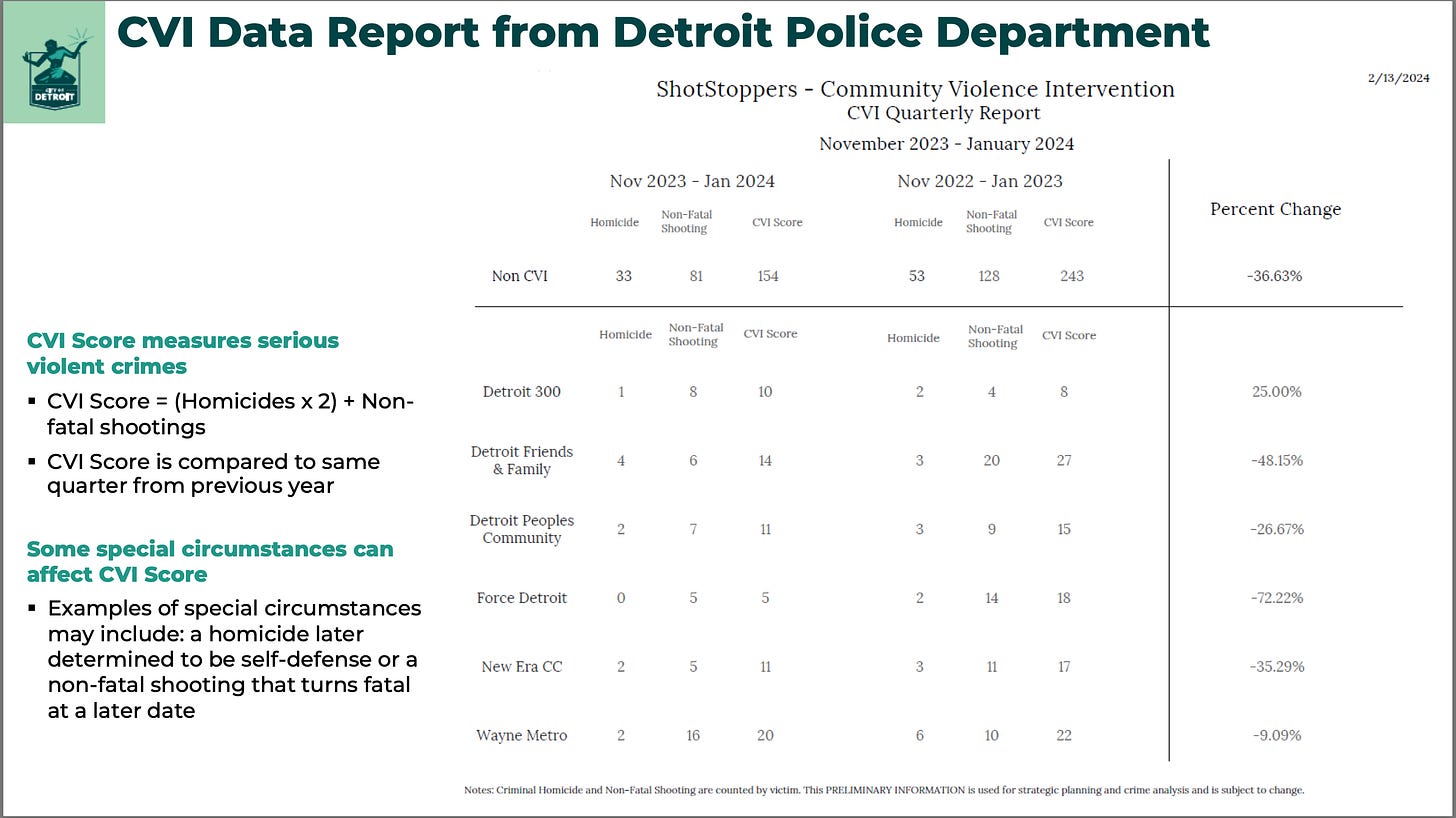

The following table says that the area where Force Detroit operates had zero homicides. The previous year there were two. The number of non-fatal shootings went down from 14 to 5. The organization allegedly gets 175 000 a quarter so one could try and calculate the impact per dollar. In contrast, a study by the National Partnership claimed that the cost of a homicide is 1.8 million when adding all the costs associated with it (Shotstoppers, Detroit). Perhaps it is the increased spending rather than the nature of the specific intervention that is having an effect? Or perhaps this is statistical noise? Or part of a general decrease in violence across the country? If we want to reduce violent crime, we need to presumably understand why these reductions happened.

This table shows how these groups report data. The data is quarterly. The total number of homicides went down from 19 to 13.

San Antonio: Targeting Law Enforcement

San Antonio has also suffered from higher rates of violent crime. Like the other cities, it saw a decline in the homicide rate in 2023. In this case, the approach to curb crime is more traditional and it has three prongs. This approach increases policing in areas with more criminal activity, seeks to understand the root causes in those areas, and intervenes on specific individuals who are responsible for a lot of crime.

City officials in San Antonio superimposed a grid in the city to locate areas with the most crime. This is revised every sixty days. The city deploys extra police forces to the areas with the highest amount of crime. At first, the initiative was unpopular, according to Police Chief William McManus, because it was perceived as “boring; however, the fact that it is “working” has changed this perception (Andone & Ticker). This is a strange metric by which to evaluate crime reduction strategies, is it not? We haven't delved deeper into this one.

On the other hand, Mc-Kee Rodriguez, a council person, claimed that these statistics do not track gun shots and hence they do not mean much for citizens’ fears. She added,“I don't know that numbers mean much when your reality feels like something different” (Andone & Ticker). One citizen, Ray Kelly A Vaktumore, said “safety and homicides are two different spectrums” and according to him “we will never feel safe because we always had to rely on our own experience” (Andone & Ticker).

We have not looked into the specifics of this program. We are interested in learning more about their claims regarding the causes of crime and what measures they are taking to combat them.

Conclusions

Implementing policies to curb crime is difficult. It is also challenging to ascertain the extent to which policies are working, whether other interventions would have worked better, and if anything should be done differently. In reviewing these reports we want to highlight a few points:

Crime as disease: Many of these programs are treating crime and violence as public health issues and thus devising public health analytical approaches and interventions. For example, this includes preventative strategies and how these areas are divided/studied, and intervening on superspreaders. Do these models work? Are these models desirable? Do the crimes get displaced elsewhere?

Methodology: Neither of us are criminologists nor statisticians. However, we find that many of these methods appear to be easily massageable. Some places only count homicide and ignore non-fatal shootings. Others separated areas into arbitrary spaces; how do these divisions affect outcomes (similar to redistricting and elections?) ? What kind of background statistical noise is there? Have there been changes in how categories of crime are defined? How do investigators parse out the effect of an intervention from changes that would have occurred otherwise?

Using Credible Messengers: Initiatives like the ones in Detroit and Baltimore aim to use people who have a history of violence to reach out to prospective perpetrators and/or victims. Other organizations have used individuals like these to coerce other people.

Local solutions: It is interesting to see efforts to focus on localized solutions to problems like violence. Most of these interventions are small and decentralized even if funding is centralized. One of the problems with centralized solutions can be that central authorities over simplify to make a diverse space legible. On the other hand, localized solutions can be hard to compare to one another, hard to replicate, and may lack broader institutional and structural support. To what extent are these localized approaches the best way to reduce the incidence of crime?

Expensive: These programs require funding and proponents argued that similar attempts failed because they lacked more money. How can decision makers decide where to invest and how much to invest? How much would these crimes cost the community if they had not been prevented?

Civil Liberties: These interventions could raise issues related to identifying people as possible perpetrators and/or victims. Critics in Baltimore have argued that individuals who may have only committed a misdemeanor are pleading guilty to felonies as a result of being charged as a group. How does this impact an individual in the long term? Are these policies fair considering that an individual with the same hardships who is not identified as a prospective perpetrator is ineligible for support?

Press reporting: We do not want to minimize the work of any of these groups and we are certain that for the individuals involved they could have been impactful. Yet headlines about a 72% reduction in violent crime rarely mention that homicides in that area changed from two to zero. What role does the media have to play here? Does the common American know that violent crime has drastically dropped in 2023 and 2024?

Originally, we meant this to be one of our shortest posts. As you can see, we found that we had to dive deeper into these problems so we could cover them adequately.