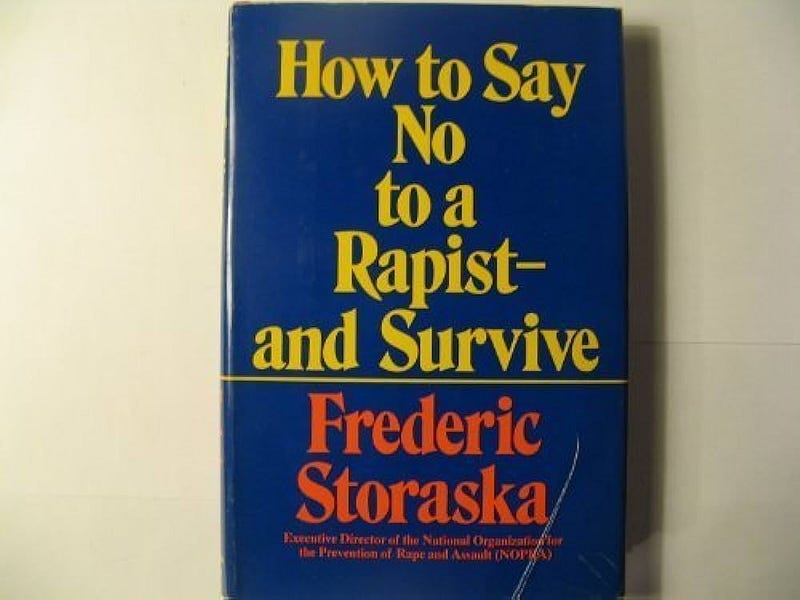

How to Say No to A Rapist

A Controversial and Immensely Popular Guide to Deal with Rape

A Controversial and Immensely Popular Guide to Deal with Rape

Rape is one of the most horrendous crimes.

There have been many efforts to reduce the incidence of rape. In this article we explore a program that was widely popular in the seventies. The study of rape is challenging because many rapes continue to go unreported, the lack of information about rapes that almost happened, and the absence of detail about those that end in murder. Studying this crime is challenging because gathering data is difficult as it is not possible to explore what would have happened if anyone would have acted differently. There are several cases where the police gave similar advice to the one Storaska gave (TTS, 1976)

Frederic Storaska’s program was also criticized as disrespectful, insensitive, and dangerous. By 1975 Storaska had presented his program at over 500 universities and colleges (SLT, 1975). His rape prevention program was said to be useful, the best, and often criticised wrongly (Nicol, 1979). Storaska also wrote what one reporter called an “exceptional new book” (Miller, 1975). Although the book has been mostly forgotten it continues to stir some debate on Amazon where fifteen reviewers have given Storaska’s book five stars and three people have given it one star. Marain wrote one of these reviews and said that the “book will change your life”. Another reviewer claims that the book saved her life.

In 1978 members of the Ottawa Rape Crisis Center “gave each other victory hugs Wednesday after city council decided a controversial film on raise show not be shown to students” despite it being endorsed by the police department and the department of education (Brady 1978). Other writers interpreted the film and book very differently, one concluded that he could not “see any justification for the present outcry against the film” (Dormer, 1978).

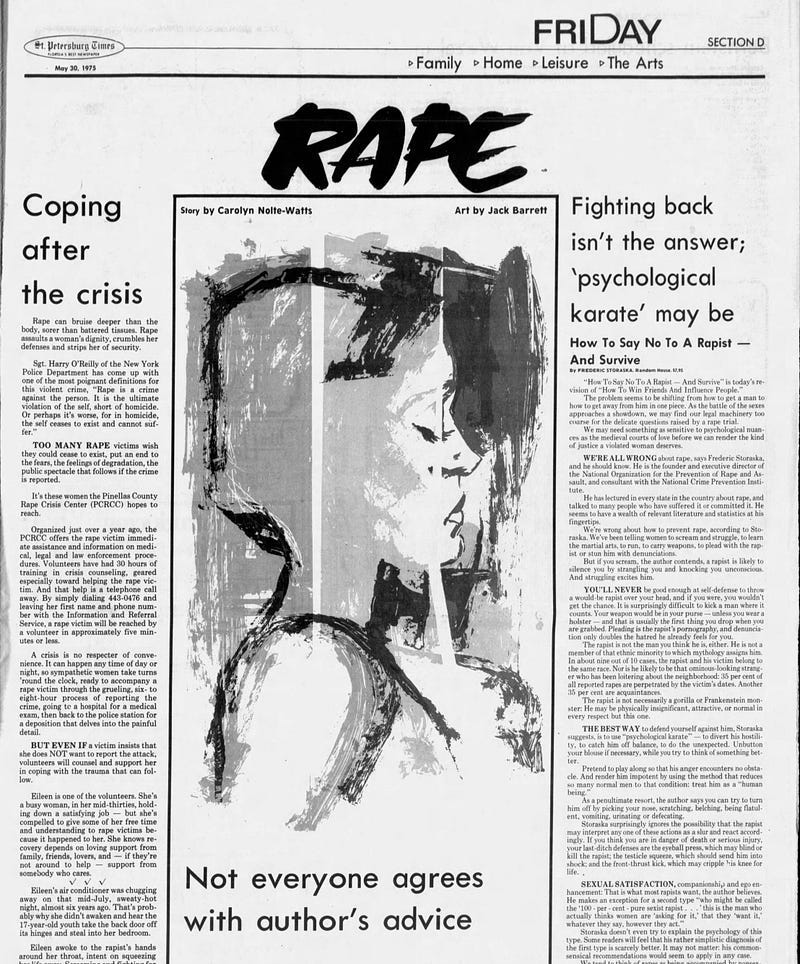

Storaska’s Advice

In short, Storaska was more concerned about reducing the number of women who were killed during a sexual assault rather than eliminating rape. You can read more about his program in our other article. He thought that resisting sexual assault made it more likely that women would be badly hurt and hence suggested that they should appear complicit until they found an opportunity to safely escape. Storaska insisted that violence was worse than the sex involved in rape, “I’ll tell you one thing: you’ll be a lot more able to handle sex than violence.” The data he claimed to have collected showed that most rapes do not result in death or injury “beyond the sexual assault” (p.4). In his view a woman could handle rape better than death or being badly injured.

Storaska thought that rapists were always responsible for their crimes regardless of how a woman may have behaved. His suggestions can be summarized as follows:

Think Clearly: thinking rationally allows you to make good decisions

Treat the rapist as a “human being”, not because they deserve to be treated nicely, but because this makes it more likely that you will be able to react and escape unharmed.

Gain his confidence: so you can distract him and react intelligently.

Go along until you can safely react.

Use your imagination and find ways to prevent the rape from occurring.

Storaska’s Presentation Style

Storaska’s talks were informal and he often tried to be humorous. For some this approach was essential to his success and the efficacy of the program. One journalist wrote that he had “a tight control over the audience through the lecture. One minute everyone rolled with laughter and the next all were silent” (Godwin, 1975). A reviewer lauded Storaska’s film because of the “light manner” in which he presents facts that would otherwise be “frightening” (Fogleman, 1977). This reviewer added that Storaska adds humor and comes across in such a dynamic way that any woman who sees this film will never forget it” (Fogleman, 1977). Others were appalled that he made jokes when discussing rape.

In 1975 a group of women chanting “rape is not a joke” interrupted one of his talks at Longmeadow Mass Bay Path Junior college (Colander, 1975). Storaska’s tone is admittedly unusual; he wrote, “the main event in rape, physically, is sexual intercourse, which is something you may be delighted to have–under other circumstances. So what the rapist wants from you is not a terrible thing at all, in itself” (Stroaska, p.2). Another speech was interrupted by the the Springfield Rape Crisis Center who expressed their discontent with Storaska’s jokes and advice (Talaber, 1975). Other groups like the Macomb chapter of the National Organization for Women complained that it “treats a serious subject like a joke” (Fireman, 1976).

Stroraska’s Expertise and Motivations Are Questioned

Another contentious issue was whether Storaska was an expert or not. A journalist wrote that “Storaska has not published in scholarly journals. He has no college degree, although he is approximately a semester away from earning one at North Carolina State University” (Bruning, 1975). Another writer insisted that “you are bound to find disagreement among the experts. I go along with Dr James Selkin, director of the Center for the Study of Violence at Denver General Hospital.” His advice is “AGAINST being calm or trying to talk the attacker out of it.” He argued that “it is important to resist rape violently, at the beginning” to get the attacker to run off (Landers, 1975).

Others claimed that Storaska was only interested in money. Bruning argued that “I have the clear and unequivocal impression that he is just exploiting the women’s movement and the rape issue for personal gain” (1975). Another journalist reported the prices Storaska was charging to make a similar point. The film was priced at 750 USD (about 4450 USD in 2023 dollars), and it could be rented for 250 USD per day. He charged 1000 dollars per talk plus expenses. (Fields, 1975). In 1975 the National Organization for Women alleged he was an entrepreneur and not a social scientist and asked the New York Attorney General to investigate the nature of his activities (Bruning, 1975). In 1976 James Bannon, a Detroit Police officer, called Storaska a “huckster…parading around and giving very bad advice to women” (AP, 1976).

At some point Storaska moved to investment banking. He was said to zealously pursue accounts and ignore legal boundaries in this pursuit. He made millions of dollars in “unauthorized trades and used Prudential’s commission system to generate interest-free loans for himself and diverted cash from Prudential through a shell company” (Eichenwald, 1993). Considering his crimes as a trader the accusations that he exploited violence against women and the fears these raised should be taken seriously. Even if he may have profited, his advice could still have been a genuine attempt to help women. What do you think?

Challenging Storaska’s Claims

Storaska was often accused of treating rape as a minor crime. He claimed that “death, mutilation, disease, death of a loved one” could be worse (Storaska, p.3). He also claimed that in most rapes there is no harm “beyond the sexual assault” (p.4). A commentator wrote, “I have trouble with his kind of statistics. I’d say that 100 percent of rape victims are hurt” (Robb, 1975). Mary Ann Largen, coordinator of the National Organization for Women (N.O.W.), called Storaska’s work “insulting and misleading” because it relies on “unverified assumptions” (Bruning, 1975).

One of the debates was whether women should immediately try to forcibly resist a likely rapist. Selkin claimed that only about 9% of women who resisted were harmed (Landers, 1975). Ms Little said “anyone who follows Storaska’s advice to submit without a struggle will get raped. Immediate resistance is the key to avoiding rape, unless the attacker has a lethal weapon like a gun or a knife.” Another women’s organization called Akron Women Against Rape criticized Storaska’s ideas because they are “in direct conflict with those promoted by many police departments and women’s groups” (Reader, 1975). Likewise, the Macomb County Chapter of N.O.W. started a campaign against Storaska’s program because it gives “bad advice” (Fireman, 1976) . The Vancouver Rape Relief argued that they had received complaints from women who followed Storaska’s advice (CP 1978).

Some of the studies conducted at the time seemed to suggest that resistance is the best strategy. A study conducted in 1976 reviewed 60 rapes and 48 cases of attempted rape and found that “a higher level of injury was suffered by non-resisting victims, more of whom were raped than those who resisted” (IDN, 1980). Another study found that resistance increases the likelihood of minor injuries, but that the more “docile and compliant” women faced the biggest risk (Berman, 1980). Dr Jennie McIntyre reviewed 220 cases of attempted rape and found that women who resisted were more “successful in avoiding rape” (Berman, 1980).

Others were concerned about the legal implications of Storaska’s methods. An article in an Ottawa newspapers told the story of two women who resisted and consequently were not raped, and one that followed the advice in Storaska’s film until it was clear she would be raped. The article highlighted the concern that Storaska’s strategies would make it hard to show there was forced intercourse (Costigliola, 1978). Storaska recognized this problem, and argued the legal systems should not require physical signs of resistance.

Conclusions

There is no question that Storaska’s efforts increased the attention paid to rape prevention. His work stressed the need to reform the judicial system to better support victims of rape. He also contributed to dispelling the myth that women who are raped were asking for it. Storaska’s main aim was to reduce the number of women who were killed or that were permanently injured. He wrote, “I refuse to advocate any method of rape prevention that could cause the bodily harm or death of any person using it” (Storaska, p.26).

Undeniably rape is an appalling crime. This crime can leave both physical and psychological scars. Storaska seemed to be more concerned about preventing physical harm and to imply that psychological harm can be more easily overcome. Ultimately, he claimed to device a strategy based on evidence, reason, and logic to reduce the incidence of rape. He thought that the best way to discuss rape was through the use of humour.

At Curing Crime we aim to understand the ways in which thinkers, policy makers, and nation states have tried to reduce crime. This episode raises broader questions about crime prevention. First, what are the best ways in which to communicate information regarding crime and crime prevention? Second, given the likely impossibility of eliminating crime entirely; to what extent should there be a focus on reducing its impact? Third, what role does gender play in these discussions (we are both men and so was Storaska)? Fourth, what are the best ways to explore underlying assumptions in our thinking regarding the causes of crime, how to prevent crime, and how one should react if one is being victimized?

Authors: Christian Orlic and Lucas Heili. We are interested in this as a historical episode. Neither of us are experts or trained in counseling or preventing this type of crime. Given the subject of this article we also asked friends of ours (who are women) to read it.

Sources

Associated Press. 1976. To fight or submit — rape film battle. The San. Francisco Examiner, Dec 10, 1976, p.13.

Bart, P. B. (1981). A Study of Women Who Both Were Raped and Avoided Rape. Journal of Social Issues, 37(4), 123–137. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.1981.tb01074.x

Berman, L. 1980. Fight back, don’t talk, new rape studies suggest. Detroit Free Press, Dec 2, 1980, p.17

Brady, S. 1978. City gives rape film bad review. The Ottawa Journal, Jan 5, 1978, p.25

Broyard, A. 1975. Fighting back isn’t the answer; psychological karate may be. Tampa Bay Times, May 30, 1975, p.55,66.

Bruning, F. 1975. Not Everyone Agrees with Author’s Advice. Tampa Bay Times, May 30, 1975, p.55, 66.

Colander, P. 1975. Fast thinking, not kicking — a better way to foil rape. The Chicago Tribune. April 18 1975.

Costigliola, B. 1978. ACSW will urge RCMP to stop showing controversial film. The Citizen Ottawa, Jan 11, 1978, p.63.

CP. 1978. Seek to ban film on rape. North Bay Nugget. Jan 3, 1978, p.9.

Dormer, M. 1978. Is death superior to rape?. The Ottawa Citizen, Feb 7, 1978, p.6.

Eckardt, M. 1976. What Do You Say To A Rapist. The Sheboygan Press, Nov 23, 1976, p.10

Eicehnwald, K. 1993. Prudential’s Firm Within a Firm. New York Times, May 25, 1993, p.D1.

Fields, S. 1975. A Strategy to Survive Rape. Daily News. March 13, 1975, p.176.

Fireman, K. 1976. Women Wasn’t Anti-Rape Film Banned. Detroit Free Press, November 4, 1976, p.3.

Fogleman, D. 1977. Well Worth Seeing: Film Deals With Tactics On Warding Off Rapists. The Daily Times -News. April 6, 1977, p.17.

Godwin, M. 1975. Speaker tells how to best deter rapists. Traverse City record-Eagle. November 15th, 1975, p.13.

IDN. 1980. Rape: Giving in isn’t always safe. Irving Daily News, Jan 29, 1980, p.2.

Landers, A. 1975. Ann Landers. The La Crosse Tribune, (Wisconsin). March 30, 1975, p.47.

Miller, G. 1975. Rape Expert Says Victims Should Think before They Fight”. The Fresno Bee, Nay 5th, 1975, p.14.

Nicol, W. 1979. Rape film takes common-sense approach. The Sault Star, Oct 27, 1979, p.5.

Pawelski, D. 1975. Rape seminar to emphasize education. Rapid City Journal. April 20, 1975, p.13.

Reader, P. 1975. Treat a rapist like a human. The Akron Beacon Journal, April 10, 1975, p.16.

Reid, H. 1975. The rapists’ rights that put the woman in the wrong. The Western Daily Press (UK), p.9.

RMT. Storaska Lecture is Monday at ECU. Rocky Mountain Telegram, Nov 2, 1986, p.13.

Robb, C. 1975. A Cool Look at the risk of rape. The Boston Globe, March 28, 1975, p.21.

SLT. 1975. Rape Topic Tonight, Wednesday of Seminar at Indiana University. Simpson’s Leader-Times, p.6.

SS. 1976. How to Say No And Survive. Southtown Star, Feb 22, 1976, p.18.

Talaber, S. 1975. Rape: most common crime of violence; least reported. Daily Hampshire Gazette, April 19, 1975, p.5.

TTS. 1976. Junior Women’s Club Program on Self Defense. The Times, Streator, IL. Jan 8, 1976, p.15

TWE. 1976. Rape Defense Talks Scheduled. The Wichita Eagle, Jan 18, 1976, p.37