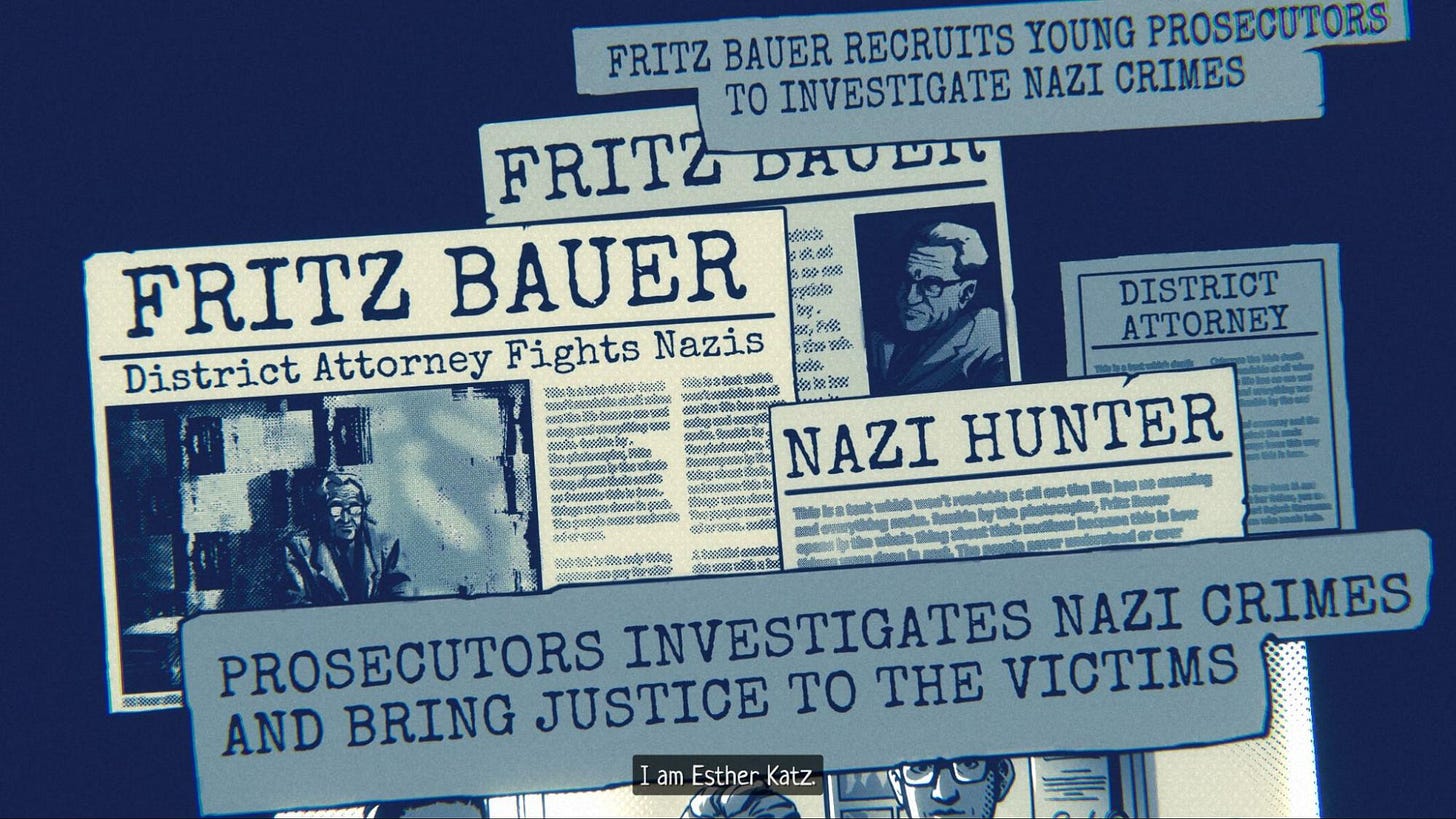

Gameifying Nazi Trials in the Darkest Files

Learning Criminology Through Play

In our last two articles on The Darkest Files, we examined the developers’ historical debates on criminology through their setting of Cold War Berlin. We covered the complicity of the post-war German government and media in pushing a ‘politics of forgetting’ of the country’s Nazi past. We also analysed how the game reflects Fritz Bauer’s own understanding of the motivations of Nazi perpetrators—‘small men’ under the state, motivated by an agglomeration of petty personal grievances and frustrations empowered by National Socialist ideology.

This week, we investigate how the game models its virtual trials of these perpetrators. The Darkest Files, through its friction between dialogue and gameplay, recreates the same dissonance Fritz Bauer felt attempting to bring a broader proto-human rights interpretation of Nazi crimes to the German court system. Players face this dissonance head on as they grapple with the imperfections of a strictly (and oftentimes disingenuously) positivist legal framework, attempting to secure the imprisonment of Nazi perpetrators.

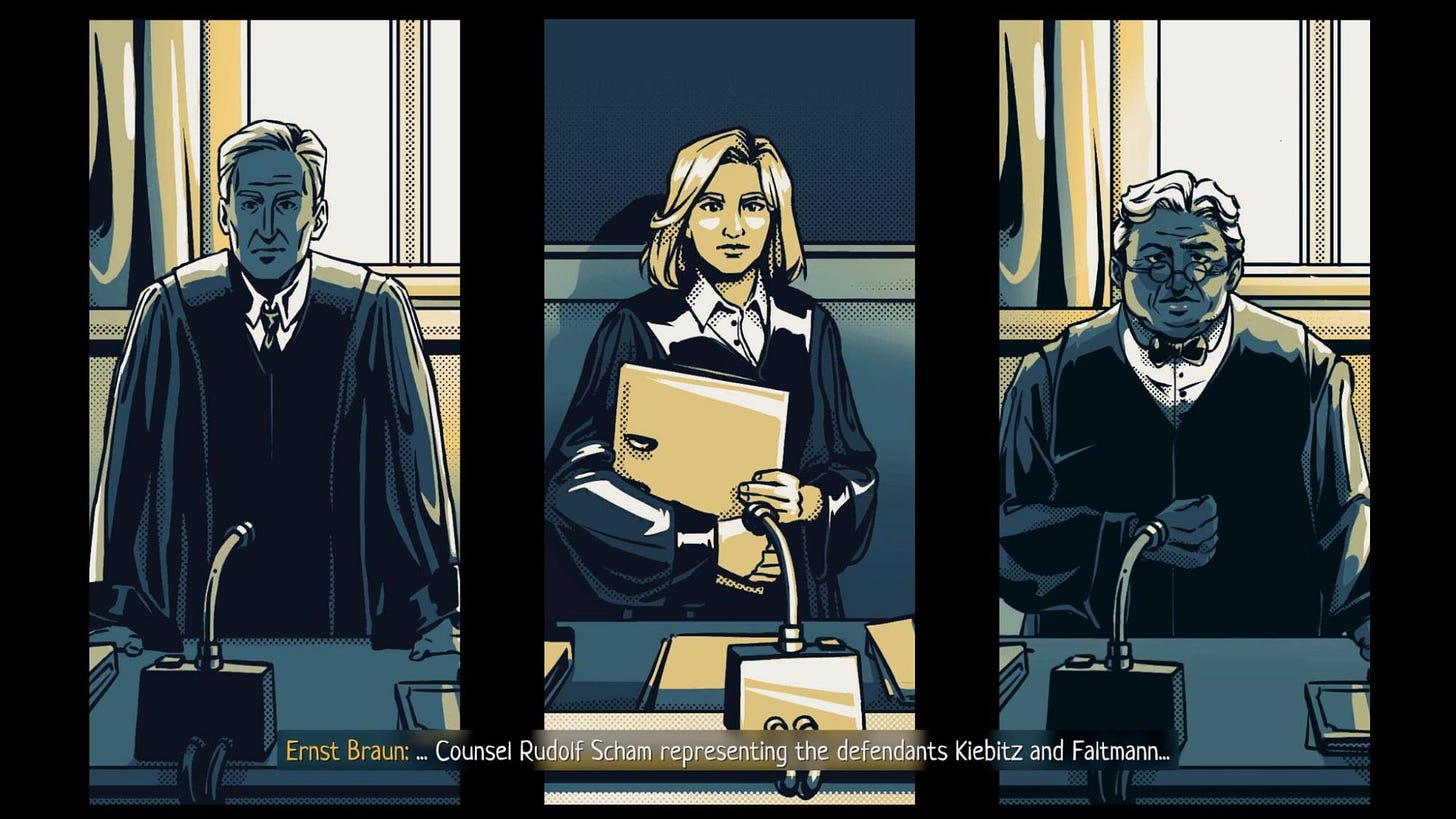

The Makings of a Virtual Court

Academics have at various times pointed fingers at the Adenauer government1, the holdovers from National Socialism going soft on their colleagues, and on the yellow press to explain why so many Nazis fell through the cracks.2 All these factors certainly played a part, but when a case reached trial, it was most often the internal workings of the legal system and prevailing attitudes that prevented successful convictions. German jurist Ingo Müller detailed how, as late as 1971, postwar courts upheld wartime executions for violating the Race Laws, for making “demoralizing remarks” regarding Hitler, or even for refusal to order executions within the Wehrmacht, as essentially lawful actions at the time.3

After the war, the new German government rolled back Nazi era statutes and reintroduced an amended version of the 1871 Penal Code, a change that ironically made prosecuting certain Nazi perpetrators even more difficult.

One such example is the 1871 code’s definition of murder as requiring an individualised base motive.4 Such laws tended to see crime as an individual engaging in asocial activity against the State. What, then, was one to do when the entire state had become criminal? Bauer wished to put Nazism itself on trial, but this was impossible within the conservative legal framework. The Darkest Files attempts to model the nature of these assumptions in German law through its virtual court.

In the game, the outcomes of the trials are a culmination of the player’s detective ability, and nothing else. Nevertheless, the developers include references to active meddling by the government in cases, hiding of evidence, and Nazi judges remaining in their posts to paint a picture of these extra-legal obstacles. The nature of the game’s medium means that it must ultimately reflect a positivist, mechanistic nature of the law. It does this for good reason as well: it would hardly be fun to have played the game correctly and be rewarded with the suspect getting off scot-free.

But the compromise in the service of fun also lays bare the tension within video games between their interactive and their story elements. For a court game to function as a game, it must have enough evidence for the player to be able to reasonably assemble the case. There must be an external truth established about the nature of the case and the parties involved. Finally, the player’s actions should be judged by the computer impartially.

Accepting these precepts for The Darkest Files means implicitly accepting the notion of an apolitical positivism governing German courts. Müller forcefully argues against “the fairy tale of positivism” pushed by post-war jurists. He enumerates how the unquestionable supremacy of the Volk and its embodiment in the Führer drove jurists’ decisions, not a tragic Prussian devotion to the letter of the law. Far from a clean break with Nazism, he instead articulates how post-war judges “clung to the values of the Third Reich” in all but name, rather than implementing actual positivist thinking.5

By modelling the positivist court, the game risks only modelling its ideological biases in its text, but not in its mechanics. Implicitly, then, the game must assume an ahistorical fairness to the trial so that it can be an enjoyable product. That decision necessarily shapes what kind of Nazi crimes can reasonably be represented in a videogame format; a reader will not demand fairness from their book, nor a viewer from their movie. A player begins the game expecting it, however.

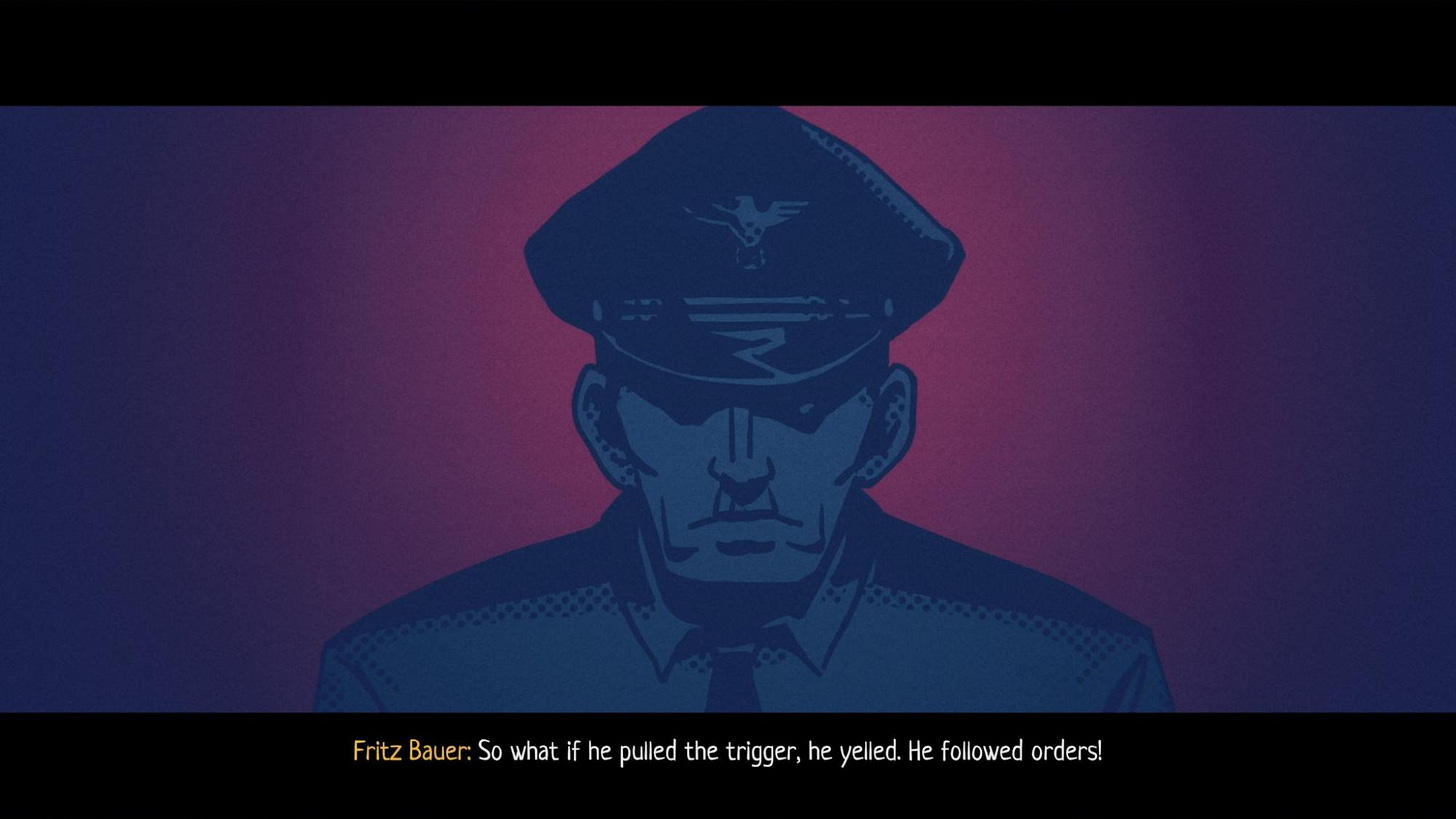

Positivism and the West German Courts

In their embrace of legal positivism, West German courts were strictly opposed to retroactivity in criminal law, even for the 1933-1945 period.6 That meant that only those who broke the law at the time had a chance to be reasonably prosecuted. It also implied that if a person did something which would now be considered criminal, but was legal at the time, they could not be punished. Thus, the player’s casework revolves around how the perpetrators violated Nazi law to commit their crimes, even if these violations were tolerated in practice.

Rebecca Wittman characterises the requirements for a successful prosecution at the Frankfurt Auschwitz Trials as such:

To prove each defendant guilty of murder, the prosecution had to show the presence of the subjective elements examined earlier: sadism, desire to kill, base motives, and so on. To show perpetration of murder (as opposed to the less serious aiding and abetting of murder), prosecutors had to prove individual initiative and knowledge of the illegality of the act, which went beyond the following of orders.7

The German code had stringent requirements to successfully charge someone with murder. Paragraphs 211 and 49 required the suspect to have individual initiative and the knowledge of the act’s illegality.

The German High Court subscribed to what is known as a subjective definition of what constituted a perpetrator. That meant that the perpetrator of a criminal act demonstrated personal intent or stood to gain from the action. In contrast, the objective definition holds the individual physically carrying out the act responsible. For example, during the National Socialist period, a woman drowned her friend’s baby at her request, yet was not found guilty of murder, as the killing was not meant to benefit herself.8

These requirements continually acted as fetters on Fritz Bauer and his prosecutorial team. They had to contend with outdated definitions that saw murder as an individualised, malicious act, and with a legal system that was all too happy to work with those definitions to not rock the boat. What this meant at the Frankfurt Auschwitz Trials was that only the most highly publicised and brutal killers were handed a murder conviction. Extra-legal murderers such as Wilhelm Boger did show individual initiative, while camp doctor Franz Lucas, who oversaw countless gassings, was only found guilty of aiding and abetting murder.9

Court Cases in the Darkest Files

In The Darkest Files, the player finds themselves suspecting the responsible party for a criminal act from the start. Both cases revolve around the execution of civilians by uniformed men complicit in the National Socialist system. The player will immediately recognize their actions as reprehensible under our own moral framework.

The job given is to establish legal culpability, a much more demanding task than moral culpability.

The first case deals with the execution of an alleged partisan by a local NSDAP chapter. The chapter’s leader in-game was even investigated by the immediate post-war trials but found innocent, as the execution complied with Nazi-era directives. The player is only able to achieve the ‘best’ trial outcome by uncovering an individual motive that overstepped even the law at the time. Thus, success is contingent on working with the law as it is, not necessarily as it should be.

Conclusions

To engage with such an imperfect system means the player will likely make mistakes. These mistakes lead to a reduced sentence or even exoneration for the perpetrator, as has happened countless times in reality. The moral culpability is well known to every player beforehand. Still, they are forced to play with a different set of legal presumptions with which they must honestly engage, no matter their disagreement, to emulate Bauer’s search for justice. The nature of the game means that making mistakes, in fact, leads to a more historically plausible outcome.

Faced with a dearth of evidence, an uncooperative society, an unfitting legal structure, and the player’s ability, it is a true achievement to mount a successful case. By focusing on ordinary court cases in such extraordinary circumstances, the game highlights the inherently political nature surrounding trials.

At the same time, its mechanics replicate many of our societal assumptions about impartiality, even if the narrative acknowledges the hostility faced by Fritz Bauer’s prosecution. The game’s court system is faithful, in the sense that it reflects German jurists hewing to positivist principles when trying Nazis. Nevertheless, if not examined critically, the player may uncritically absorb such a narrative. British statistician George Box famously said, “all models are wrong, some are useful”.

The Darkest Files is at its most useful when its own limits are acknowledged, as a jumping-off point to further probe how post-war justice was handled and mishandled.

Norbert Frei and Joel Golb, Adenauer’s Germany and the Nazi Past: The Politics of Amnesty and Integration (Columbia University Press, 2010), https://doi.org/10.7312/frei11882headhead-on-on; Theodor W. Adorno and Theodor W. Adorno, Guilt and Defense: On the Legacies of National Socialism in Postwar Germany, ed. Jeffrey K. Olick and Andrew J. Perrin (Harvard University Press, 2010)