Beyond the Archives Nov 2025: Being Tough On Crime May Not be What You Think.

Judge Teste Reflects on a Life on the Bench and His Efforts to Help Young People

We are delighted to share our interview with Steven Teske. Teske was the Chief Judge of the Juvenile Court of Clayton County in Georgia. He judged in Juvenile Courts for over twenty-five years. He testified before Congress and other legislatures on detention reform, zero-tolerance policies, and juvenile justice reform.

Teske wrote various articles on juvenile justice and child welfare, as well as a book called Reform Juvenile Justice Now. He was an adjunct Law Professor in Atlanta and currently teaches criminal justice studies and business law at Pima Community College in Tucson.

Teske’s Substact Justice ReDesigned is an accessible, thoughtful analysis of current events through the eyes of a former Judge. These articles are written with compassion, empathy, and a genuine effort to engage in dialogue. His posts connect current events to legal issues, and demonstrate the importance of taking a humane approach to these issues.

CC: What sparked your interest in being a judge? Was there anything specific? What about your interest in youth crime?

I was born in Tucson, Arizona, and after my father graduated from the University of Arizona, he accepted a position as a U.S. Public Health Advisor with the Centers for Disease Control in Atlanta, where he remained until retiring in the late 1990s. Though my family settled in Georgia, my heart never really left the Sonoran Desert. My parents knew how much I loved Tucson, so during my high school summers, they sent me back to stay with my aunt and uncle.

My uncle had recently graduated from the University of Arizona College of Law and was working as a prosecutor in the Pima County Attorney’s Office. I would ride to work with him each morning and spend the day observing courtroom proceedings. Watching justice unfold—sometimes imperfectly, but always with purpose—captivated me. It sparked my curiosity about the law and, more importantly, the role of lawyers as advocates.

While many see the law through television dramas—prosecutors and defense attorneys battling in courtrooms—I was drawn to something deeper: the power of advocacy to protect the vulnerable. Reading about the civil rights movement and landmark cases like Brown v. Board of Education, which overturned Plessy v. Ferguson and dismantled Jim Crow segregation, showed me how the law could be a tool not just for punishment, but for progress.

That realization planted the seed for what became a lifelong pursuit—to use the law as an instrument of justice, fairness, and social change. It’s what ultimately led me to the bench.

I often say I didn’t plan to become a juvenile court judge—I accidentally fell into it, and I’m grateful I did.

At the time, I was a partner in a law firm and served as a trial attorney. My firm was contracted by the Georgia Attorney General’s Office to represent state employees sued for alleged civil rights violations under Section 1983—the federal statute that allows citizens to sue government employees acting “under color of law.” The irony wasn’t lost on me: I’d once dreamed of suing the government for violating civil rights, and here I was defending it.

After several years of this work, a senior assistant attorney general called with a request. The state needed someone to step in and represent the Department of Family and Children Services (DFCS) in my home county—handling child abuse and neglect cases in juvenile court. These were civil proceedings, separate from the criminal prosecutions, and involved petitions to protect children by removing them from unsafe homes. I said yes—not wanting to bite the hand that helped feed my firm—and soon found myself immersed in the world of child welfare law.

In time, I also began handling probate matters involving incapacitated adults in need of protection. The work was demanding, but it gave me a front-row seat to the human side of justice. I came to understand how poverty, trauma, and systemic failure intersect in people’s lives—and how the courtroom can be both a place of accountability and of compassion.

A few years later, the chief judge of our juvenile court invited me to lunch. She confided that she planned to retire and encouraged me to apply for her seat. I did—and in 1999, I was appointed to the bench.

What began as an unexpected detour became my life’s calling.

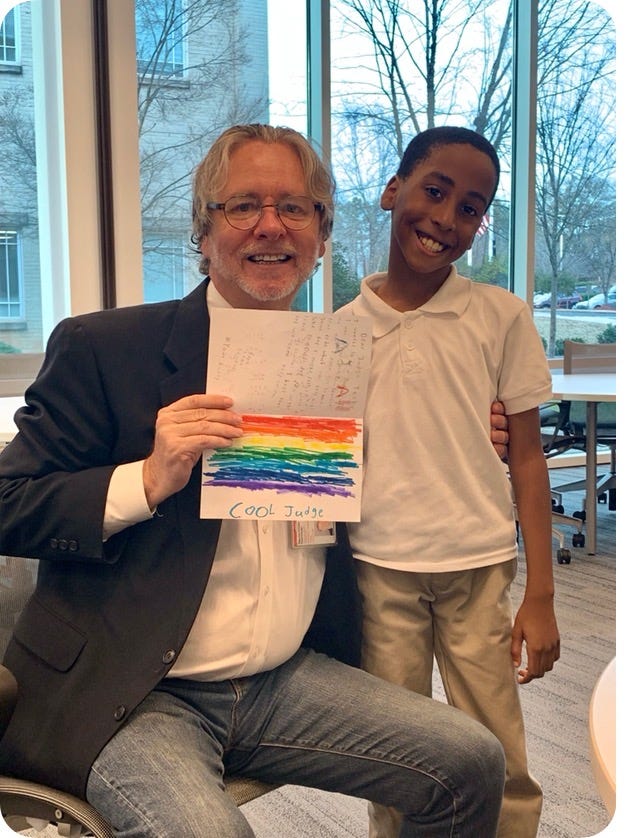

Juvenile law taught me that justice isn’t about punishment—it’s about healing, redemption, and the belief that people, especially young people, can change.

My interest in youth crime grew naturally from the moment I took the bench. The chief judge at the time knew my background—before becoming a lawyer, I had worked the inner-city streets of Atlanta in the 1980s as a parole officer, when the city’s housing projects were considered by HUD among the most dangerous in the country. I later served as the chief parole officer for Atlanta and then as the assistant director of field services for Georgia’s parole system, overseeing statewide offender programming.

That experience gave me a deep understanding of evidence-based practices that actually reduce recidivism. So when I joined the juvenile court, the chief judge asked me to take a hard look at our local juvenile justice system and identify areas for reform. I not only conducted my own study but also brought in a nationally recognized expert to provide an outside, objective assessment. I knew that credible, independent recommendations would strengthen the case for change.

The reforms that followed transformed our court. Over time, they became a national model for community-based alternatives and school-justice partnerships. By the time I retired, referrals of youth from police to the juvenile court had dropped by 82 percent—proof that when you treat kids as developing human beings instead of hardened offenders, both they and the community win.

CC: Why Substack? What do you hope to achieve here? How do you balance storytelling with academic rigour when publishing?

I chose Substack because it has become a kind of refuge for serious writers—many of whom came from major news outlets like The New York Times, The Washington Post, and others—who wanted to keep writing freely and thoughtfully after leaving traditional journalism. That says something powerful about Substack as a platform.

It’s not just another social media site; it’s a community where ideas, evidence, and integrity still matter.

I was also drawn to the quality of the writing here. When you share space with gifted and seasoned writers, you feel a healthy pressure to raise your own bar. Substack challenges me to sharpen my thinking, refine my voice, and ensure that what I publish is not just opinion, but opinion grounded in fact, data, and lived experience.

Don’t get me wrong—Substack is a place for opinion. But it’s also a place where opinions must earn their keep. To gain traction here, ideas have to be reasoned, supported, and defensible. That’s what I value most about it—and why Justice ReDesigned found its home on this platform.

My wife asked me when I launched Justice ReDesigned on Substack, what was my end goal, and I told her my goal was—and remains—to help people understand that justice is not a simple or static concept. We use the word so casually in America that I fear we’ve begun to take it for granted.

But justice, in its truest form, is complex. It’s not just about laws or verdicts—it’s about patience, sacrifice, process, mercy, and faith. It requires both courage and humility, and it demands that we look beyond ourselves to the well-being of others.

I write to remind readers that justice doesn’t live in slogans or headlines. It lives in how we govern, how we treat one another, and how we respond when power is abused.

The timing of my arrival on Substack was no accident. I began publishing shortly after Donald Trump’s second election, at a time when a flurry of executive orders began to compromise civil liberties and economic justice alike. Tariffs that hurt working families, policies that favor the powerful at the expense of the struggling—these aren’t abstractions. They’re daily injustices that reveal how fragile democracy becomes when we grow complacent. Trump’s presidency has given me no shortage of material—too much, frankly, for one writer to keep up with.

But my purpose isn’t to persuade those whose minds are closed. I write instead for those who already understand the meaning of justice and feel disheartened watching it erode. My aim is to affirm them—to tell them their frustration is legitimate, their anger righteous, and their hope still necessary. If my words can remind even a few readers that justice is worth fighting for, not as a partisan goal but as a moral one, then Justice ReDesigned will have achieved what I set out to do.

For me, the balance between storytelling and academic rigor traces back to my early education. As an Honors student in my master’s program, I took specialized courses in Argumentative Writing and Technical Writing. Argumentative writing taught me the art of persuasion through narrative—the ability to make ideas breathe and connect emotionally. Technical writing, on the other hand, instilled in me the discipline of structure, clarity, and precision. Those two worlds—heart and head—became the foundation of how I write today.

But my writing truly evolved after I married my wife, Sheryl. She’s a gifted English teacher and a natural storyteller who has an intuitive sense of rhythm and tone. Sheryl taught me how to make even the most technical ideas come alive—how to use metaphors, similes, and, when appropriate, a bit of wit or satire in the spirit of Bill Maher or Jon Stewart.

So, when readers visit Justice ReDesigned, they’ll find essays that reflect both sides of me: the academic writer who supports arguments with data, research, and legal precedent, and the storyteller who wants readers to feel the urgency of justice as much as understand it. I was a good writer before I met Sheryl, but she helped me become a better one—someone who can make complex issues not just understandable, but compelling.

CC: Briefly, what is the most pressing issue or the most intriguing unanswered question in your field. Why do you think it matters today?

One of the most intriguing unanswered questions in juvenile justice is this: Why did youth crime fall so dramatically after 1995?

During the 1980s and early 1990s, juvenile crime rose sharply across the nation. Then, almost as suddenly, it began to decline—plummeting to levels not seen since the 1950s. Despite decades of research and speculation, there’s still no definitive explanation supported by hard evidence. We can identify the forces that contributed to the earlier rise—crack cocaine, urban disinvestment, failing schools, poverty—but we don’t fully understand what caused the sudden, sustained drop.

What we do know is that our response to the rise was catastrophic. Spurred by the now-debunked “super-predator” theory advanced by political scientist John DiIulio, states across the country passed “get-tough” laws that treated children as adults. Legislatures acted on fear instead of fact—passing punitive laws even as crime rates were already starting to fall.

The consequences remain with us today: thousands of young people, now grown, are still serving adult sentences imposed during that era of panic. The lesson is sobering but vital—when we make policy based on hysteria rather than data, we create injustice in the name of preventing it. Understanding why juvenile crime fell matters, because until we do, we’ll never stop swinging between overreaction and neglect in how we respond to youth behavior.

CC: What’s the most surprising or counterintuitive thing you’ve learned in your research?

The most surprising—and counterintuitive—lesson I’ve learned in over two decades of juvenile justice reform is this: what looks soft on crime is what’s truly tough on crime.

Our instincts tell us that being “tough” means harsher sentences, more prisons, and treating kids like adults. But the evidence tells a very different story. When we react to crime with punishment alone, we often make things worse. In fact, the harsher we are, the more likely we are to increase recidivism.

This misunderstanding goes back to the mid-1970s, when sociologist Robert Martinson published what became known as the “Nothing Works” article. He concluded that no programs effectively reduced reoffending—a claim that sent shockwaves through criminology and corrections. Ironically, Martinson’s pessimism sparked a wave of serious research that proved the opposite. Once we began evaluating programs with scientific rigor, we discovered that many interventions do work when they are evidence-based and properly targeted.

We now know that offenders aren’t all alike. Risk assessment tools can identify who is high risk versus low risk to reoffend. That distinction matters. If we treat low-risk offenders like high-risk offenders—over-supervising or incarcerating them—we actually make them worse. Conversely, if we treat high-risk offenders like low-risk ones, we waste resources and see no improvement. The key is to match the intensity of supervision and services to each individual’s needs.

Those needs—what we call criminogenic factors—include issues like impulsivity, antisocial peers, family dysfunction, substance abuse, and poor educational engagement. By addressing these factors through targeted, evidence-based programs such as Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, Functional Family Therapy, and Multi-Systemic Therapy, we can rewire thinking patterns, heal families, and reduce crime.

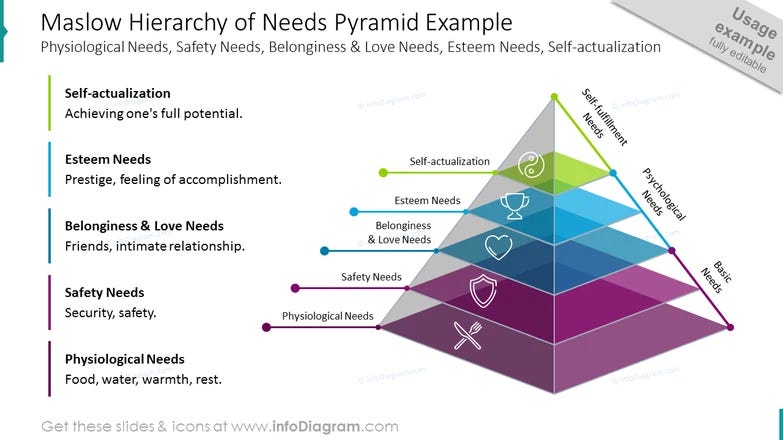

When I applied these principles on the bench, we also recognized that kids can’t focus on changing their behavior if their basic needs—food, housing, transportation, safety—aren’t met. So we used Maslow’s hierarchy of needs as a foundation, ensuring that families had stability before asking them to engage in therapy or skill-building programs.

This approach is far more complex than simply locking someone up—but it works. In my jurisdiction, juvenile crime referrals dropped by 82%. And because every kid eventually becomes an adult, preventing delinquency today prevents adult crime tomorrow.

So yes—what looks soft on crime is actually tough on crime. The real strength lies not in punishment, but in the courage to do what works.

CC: Are there any historical cases or theories that you believe deserve more attention? Why? Are there any particular rulings?

One issue I believe deserves far more attention is the question of whether juveniles who face long-term incarceration should have the same right to a jury trial as adults.

Under current law, adults charged with offenses carrying more than six months of incarceration are entitled to a jury trial under the Sixth Amendment. Juveniles, however, are not—despite the fact that many states now allow youth to be confined for years in what are euphemistically called “Youth Development Campuses.” In reality, these facilities often resemble adult prisons, complete with razor wire and isolation units.

This discrepancy stems from the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1971 decision in McKeiver v. Pennsylvania, where the Court held that juveniles do not have a constitutional right to a jury trial. At the time, the juvenile system was viewed as “rehabilitative, not punitive,” and the Court feared that importing adult procedures would destroy its supposed informality and benevolence. But half a century later, the juvenile system has changed dramatically. In the wake of the “super-predator” panic of the 1990s, legislatures across the country adopted laws that blurred the line between juvenile and adult justice. Children are now routinely tried as adults or confined in conditions indistinguishable from adult prisons.

Given that reality, it’s time to reexamine McKeiver. If we are going to treat juveniles like adults in sentencing and confinement, then fundamental fairness demands they receive the same constitutional protections when determining guilt or innocence. The right to a jury trial—one of our most sacred guarantees—should not depend on age when the consequences are measured in years of lost freedom.

CC: What books, films, or documentaries would you recommend for someone looking to understand your field better?

Two works stand out for anyone who wants to truly understand the field of juvenile justice—its promise when grounded in research, and its peril when it strays from it.

A Handbook for Evidence-Based Juvenile Justice Systems

The first is A Handbook for Evidence-Based Juvenile Justice Systems by James C. Howell, John Wilson, Mark Lipsey, Megan Howell, and Nancy Hodges. This book is an essential resource for anyone interested in how data-driven practices can transform youth justice. It brings together decades of research on effective interventions, policy reform, and the use of technology to reduce recidivism. The authors emphasize the enormous payoff in identifying and treating the relatively small number of youth who become serious, violent, or chronic offenders—and they outline a comprehensive, evidence-based strategy for doing just that.

The framework they present—the Comprehensive Strategy for Serious, Violent, and Chronic Juvenile Offenders—recognizes that early intervention, developmental understanding, and targeted treatment make communities safer than incarceration ever will. I’m honored that my School-Justice Partnership model is featured in this book as part of that evidence-based framework.

The second is Kids for Cash by Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist William Ecenbarger. It’s a sobering account of how juvenile justice can go terribly wrong when ethics and evidence are ignored. The book exposes the infamous Luzerne County, Pennsylvania scandal—where two judges accepted millions in kickbacks for sending thousands of children to for-profit detention centers, often after sham hearings. It’s part true-crime thriller, part moral reckoning.

Ecenbarger’s book—and the 2014 documentary of the same name—brought national attention to one of the darkest chapters in juvenile justice. It also discusses my work and the School-Justice Partnership model as a national safeguard against the kind of abuses that occurred in Luzerne County. Following the scandal, I was invited to meet privately with Pennsylvania’s judges to discuss reform and accountability—a conversation that, while confidential, was deeply humbling for everyone involved.

Together, these two books capture both sides of the justice system: the research-based path that leads to rehabilitation—and the moral collapse that occurs when power and profit take its place.

CC: If the public could grasp just one key idea about crime and justice, what would it be and why?

For far too long, our approach to crime has been almost entirely punitive—focused solely on the offender and the punishment to be imposed. We’ve convinced ourselves that once the sentence is handed down, justice has been done. But real justice is far more complex. It requires that we look at the harm caused not only to individuals, but to relationships and communities.

Restorative justice expands the lens. It recognizes three stakeholders in every crime: the offender, the victim, and the community. It seeks to repair harm by including the victim’s voice, fostering accountability in the offender, and strengthening the fabric of the community that both share.

When done safely and voluntarily, restorative practices can bring victims and offenders together in structured dialogue—giving victims the opportunity to explain the impact of the crime, and giving offenders the chance to take meaningful responsibility. Even in cases involving serious or violent crimes, research shows the power of restorative communication.

A remarkable study presented in a TED Talk by neuroscientist Dan Reisel found that violent offenders who engaged in restorative justice programs showed measurable changes in brain activity—specifically, reduced volatility and increased empathy after months of mediated interaction with victims.

Restorative justice doesn’t mean being “soft” on crime—it means being smart on healing. It reminds us that justice isn’t complete until the harm has been addressed for everyone involved.

CC: Your articles often show you to be a deeply empathetic person who thinks that an individual’s context significantly affects their life. How has your career as a judge influenced your thinking, specifically as it relates to people who commit crimes?

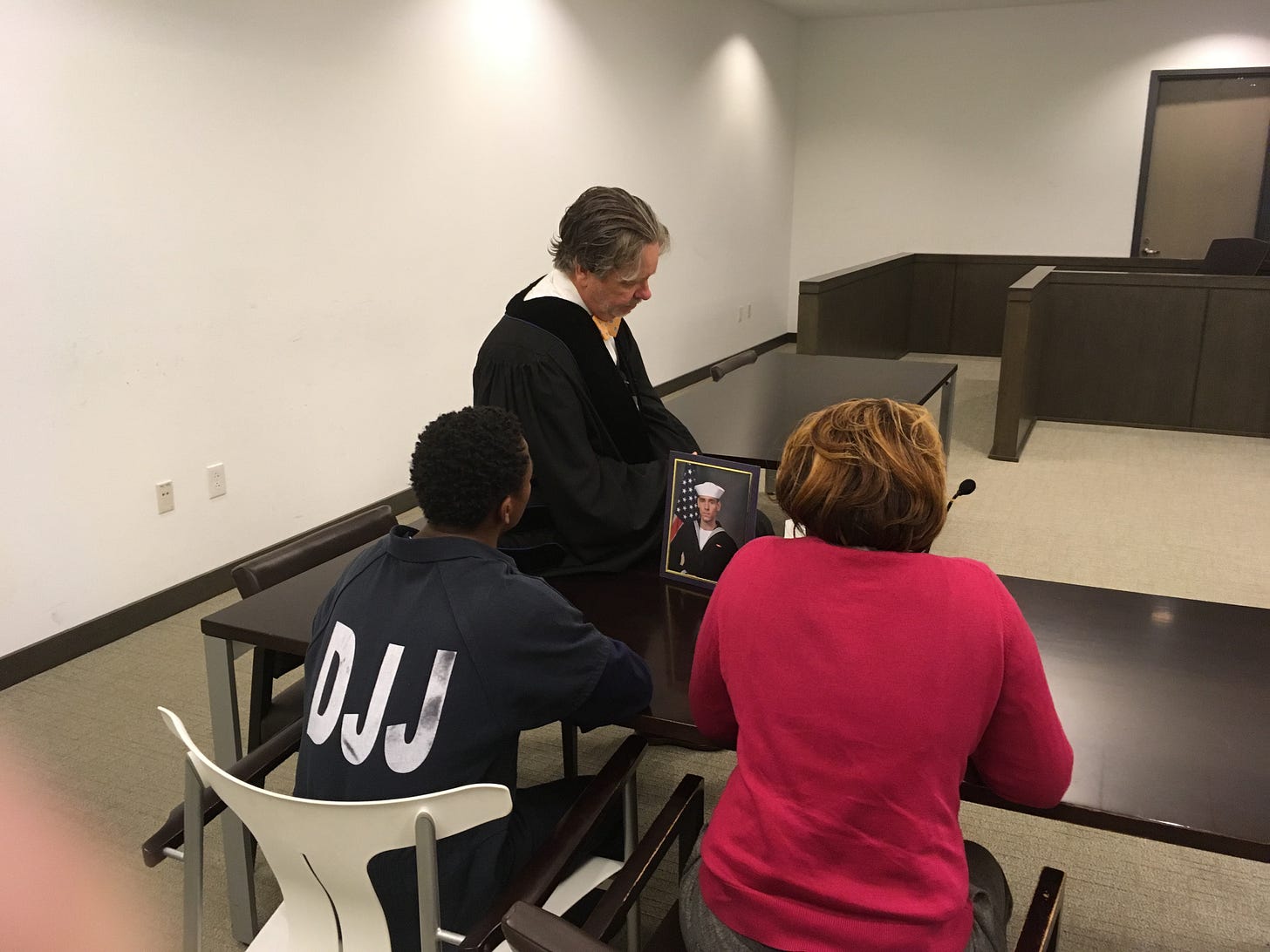

There’s a reason we hold hearings: to see the person and to hear the person. What’s written on paper is never enough. I’ve read countless reports recommending harsh sentences—some of which seemed justified—until I met the individual behind the file.

One case I’ll never forget is Will Lewis, a 15-year-old lieutenant in a gang involved in a series of robberies. The report recommended sending him to a youth prison for five years, and based on what I read, he probably deserved it. But when I met him in person, I saw something different. He was articulate, intelligent, and genuinely remorseful. More importantly, I saw potential.

I continued the hearing and dug deeper. Will had seven siblings, no father at home, and a mother who was evicted every few months. After their last eviction, they moved across the county, where Will reconnected with an old school friend who had joined a gang. When Will confided that he was tired of being homeless, his friend told him that if he joined, he’d never be evicted again—they’d make sure the rent was paid. To a 15-year-old boy desperate to protect his family, that sounded like salvation. And for a while, it was—they had food, a roof, and stability.

That’s Maslow’s hierarchy of needs in real life. Will wasn’t chasing crime; he was chasing security. Once we helped his mother secure housing assistance, SNAP, and Medicaid, I placed Will in our accountability court—the Second Chance Program for high-risk youth. He not only completed the program but graduated high school, earned a bachelor’s degree, and went on to complete a master’s in cybersecurity. Today, he has a successful career and is a taxpayer, not a defendant.

My years on the bench taught me that we can’t sentence people from a distance. Context matters. Every life has a story, and until we take the time to understand it, justice will always fall short. My mother used to tell me, “Steve, if it’s easy, it’s probably not the right thing to do.” She was right. True justice requires effort—and empathy.

CC: What are the biggest challenges judges face when ruling on youth crimes? Do you think the current options for convicted youth are enough?

One of the greatest challenges judges face in youth crime cases is convincing the public—and sometimes even fellow policymakers—that incarceration should not be our default response. This is especially difficult in communities that equate “tough on crime” with being harsh, when in reality the evidence shows that what looks soft is what truly works.

For judges who understand evidence-based practices, the challenge is not the courtroom—it’s public perception. Community-based programs, restorative approaches, and treatment models don’t always look like justice to the public. They require patience, resources, and faith in data, which is a hard sell in a world accustomed to immediate punishment and nightly crime headlines.

I was fortunate. In more than two decades on the bench, I never had a high-profile case that triggered a media frenzy questioning my approach. But my district attorney once reminded me that I had often said it was only a matter of time before a tragedy would test our resolve—a rare case where a youth in one of our programs might reoffend in a serious way. And when it happened, she told me, “Judge, we’re ready for it.”

She was right. We had the data. We could show that while about 65% of youth released from secure confinement reoffend within three years, only 17% of those in our Second Chance accountability program did. So yes, one case drew painful attention—but the broader truth remained: the old punitive model would have produced more crime, not less.

That’s the paradox judges face every day. The public demands certainty, but justice deals in probabilities. My job was to make choices that gave kids the highest probability of success, even if it meant accepting the smallest chance of failure. Because real leadership—especially in judging—means doing what’s right, not what’s easy.

CC: What role do you think science and medicine should play in the courtroom? Do you worry about how these can be exploited?

Science and medicine now play a vital role in the courtroom, especially since we began asking a fundamental question: what actually works to reduce crime?

Decades ago, sociologist Robert Martinson published what became known as the “Nothing Works” article, claiming that no program effectively reduced recidivism. Ironically, that article changed everything. It sparked a wave of legitimate research into correctional and therapeutic practices, leading to the evidence-based revolution we rely on today.

Now we have data—much of it accessible through the U.S. Department of Justice’s website, crimesolutions.gov—that categorizes which programs are proven effective, which show promise, and which do not. From cognitive behavioral therapy to family-based interventions, science gives judges the tools to make informed decisions rather than intuitive ones.

But with progress comes risk. The term “evidence-based” has become a marketing label, and there’s a real danger of exploitation by entrepreneurs who see opportunity more than obligation. Too many programs claim scientific credibility without implementing their methods with fidelity—the rigorous adherence to the structure, dosage, and evaluation that make them evidence-based in the first place.

Courts and correctional systems must therefore be discerning consumers of science. It’s not enough to adopt a program with a good name; we must ensure it’s delivered with integrity. When science is respected and implemented faithfully, it becomes justice’s strongest ally. When it’s misused or commercialized, it becomes another form of injustice—disguised as innovation.

CC: You must find many dark, disturbing, and challenging materials during your legal career. How do you deal with this work?

The hardest part of my career has never been the law—it’s been the suffering I’ve had to witness. Over the years, I’ve presided over cases that no human being should ever have to hear: a six-month-old child raped by a mother’s boyfriend; a mother with schizophrenia who, believing voices that told her her infant was possessed by a demon, placed her baby in scalding water to “drive the demon out.” These images never leave you. Even now, as I talk about them, I feel the same tears I did the day I heard the testimony.

What I’ve come to understand is that judges, social workers, and police officers often carry secondary trauma. We absorb the pain we encounter, and it leaves an imprint. For me, the only way through it has been family—my wife, Sheryl, most of all. She is my refuge. When I’ve had a brutal day, I can break down in her arms and cry, and she just holds me until the world feels safe again.

But I also know there are so many people—victims, parents, even professionals—who carry their trauma alone. Remembering them keeps me humble and grateful. It reminds me that empathy isn’t just a professional asset; it’s a moral responsibility.

In the end, what sustains me is love—my wife’s, my family’s, and the kind that still believes even in the face of horror, humanity can heal.

CC: We think our readers would find your work valuable. Could you recommend 2-3 of your posts?

Thank you — I’d be honored to share a few pieces that capture the spirit of my work on Justice ReDesigned.

If your readers are interested in juvenile justice reform, I’d recommend starting with “The Cost of Cruelty: Why the ‘Get Tough’ Approach to Juvenile Crime Fails Everyone.”

In this essay, I unpack decades of data showing that harsh sentencing and “adult time for adult crime” rhetoric do more harm than good—creating more victims, not fewer. It’s both a moral and fiscal argument for replacing retribution with evidence-based rehabilitation.

A second piece I’d suggest is “When Lawmakers Lock the Gate and Throw Away the Key: Why Maryland—and My Own State—Must Let Judges Judge.” This article looks at the dangers of mandatory minimums and legislative overreach that strip discretion from judges. It’s a call to restore judicial judgment and human context to a system that too often values politics over people.

Both essays reflect what Justice ReDesigned is all about: reimagining justice as something deeper than punishment—something rooted in fairness, data, and humanity.

It was a real pleasure to collaborate with Judge Teske, and I hope you Subscribe to his wonderful Substack.