Beyond the Archives: How The Darkest Files Puts the ‘Small Men’ of Nazism on Trial

A Video Game Exploring the Prosecution of Nazi Perpetrators

Curing Crime is excited to expand Beyond the Archives Beyond Substack. In this post, we share a conversation with Jörg Friedrich and Luca Zedda, game director and narrative designer at Paintbucket Games, about their latest game, The Darkest Files.

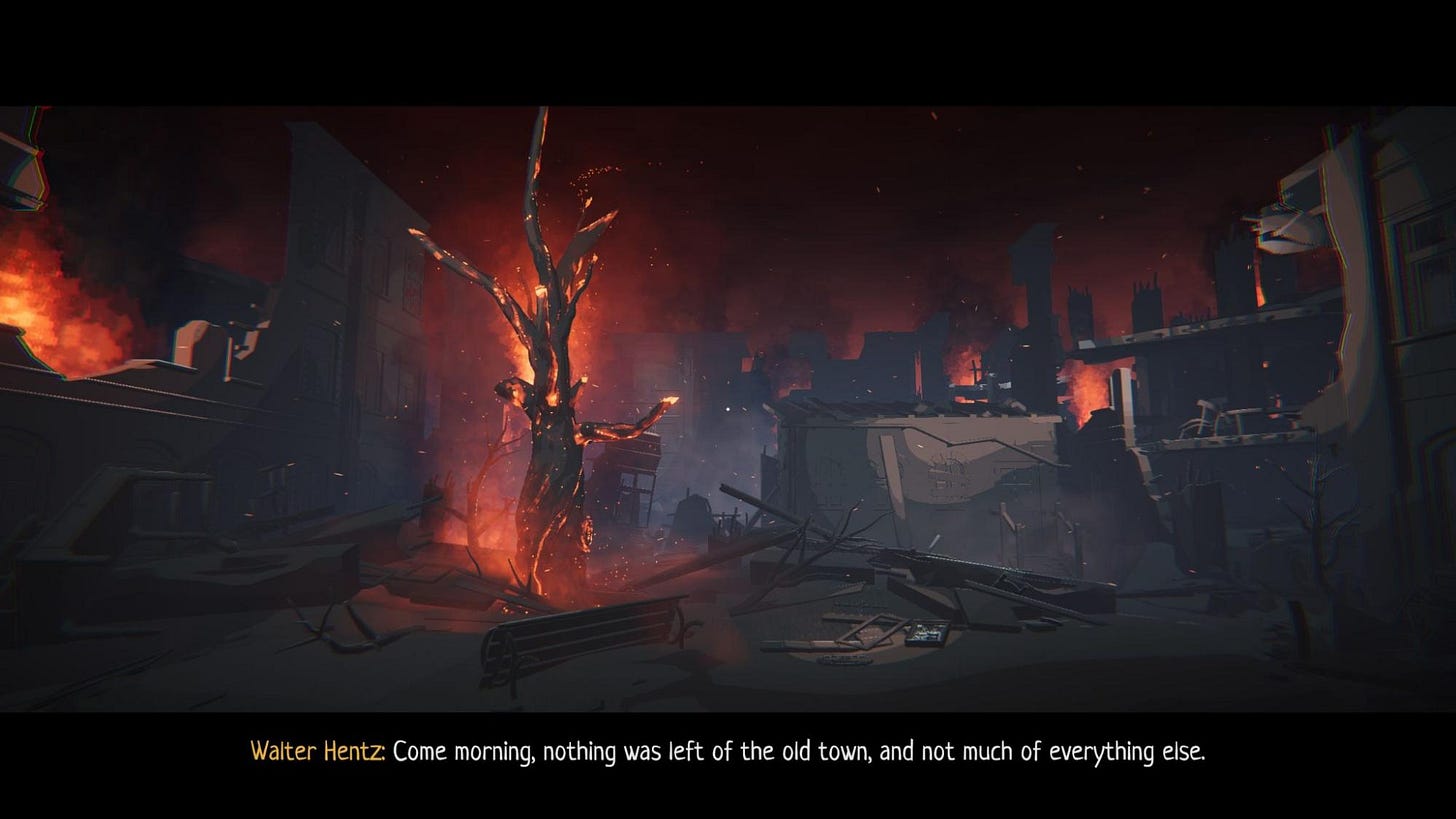

The Darkest Files is a detective game where players take the role of an investigator in Fritz Bauer's anti-Nazi team. Their goal is to prosecute fictionalized Nazi crimes in post-war West Germany. It explores the violence of the ‘small men’ of the regime, rather than the more well-known projects of mass murder and forced labor. One of the game’s strengths is that it makes modern players reconsider responsibility for these crimes by putting them in the shoes of these unsung anti-Nazi prosecutors. Throughout, they deal with the disinterest, obstructions, and outright hostility of the general public in post-war Germany.

We wanted to thank @Jovan, who interviewed the game developers and who has collaborated with Curing Crime before.

CC: How did the initial idea for the game come about? At what point did Paintbucket settle on Fritz Bauer’s team?

The idea came when we were developing the final chapter of Through the Darkest of Times, which ends with the end of the war. We were wondering: what happened after? Where did all the bystanders, perpetrators, surviving victims and the few who had resisted go?

The original concept was very different to what The Darkest Files (TDF) is today: it was a strategy game similar to Through the Darkest of Times, clues appeared on a map and you sent out investigators to chase perpetrators. Yet, when we started to prototype this concept, we realized the game mechanics would require lots of cases, leaving only very little room to tell about each one, and since we always wanted to use real cases, this didn’t feel appropriate. So we decided to go back to the drawing board and try another design: the result was the concept of a first person detective game, with only very few cases but giving each of them a lot more room. Of course we always knew about Fritz Bauer but he wouldn’t have fitted in the original concept. In the new one he did, so we changed everything to tailor it around this idea of the player being part of Fritz Bauer‘s team.

CC: What was your research process and what were your sources when designing the historically-inspired aspects of the game? Was the type of research different from your previous projects?

Especially in the beginning, we got advice from Gregor Holzinger, a historian from Vienna, specialized in NS perpetrator stories.

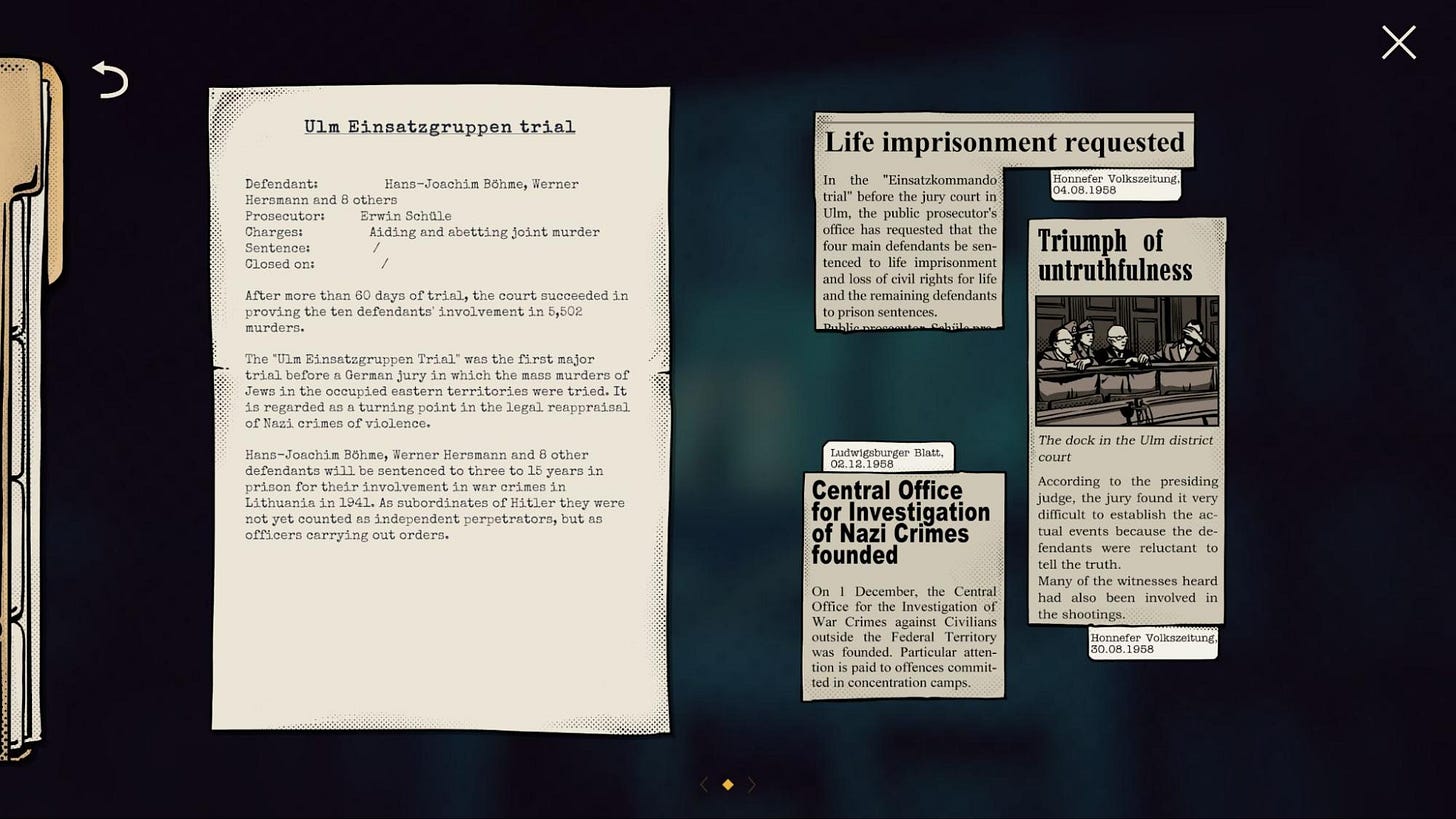

We also talked to a lawyer who gave us advice on the procedures and laws that applied. I am not sure when and how but we found pretty early a Dutch online archive where all murder trials against NS perpetrators from 1949 - 1960 can be read - that was the main source for our research.

CC: How did you go about building a picture of the real-life Fritz Bauer, and what role did you envision him playing in the overall game’s narrative?

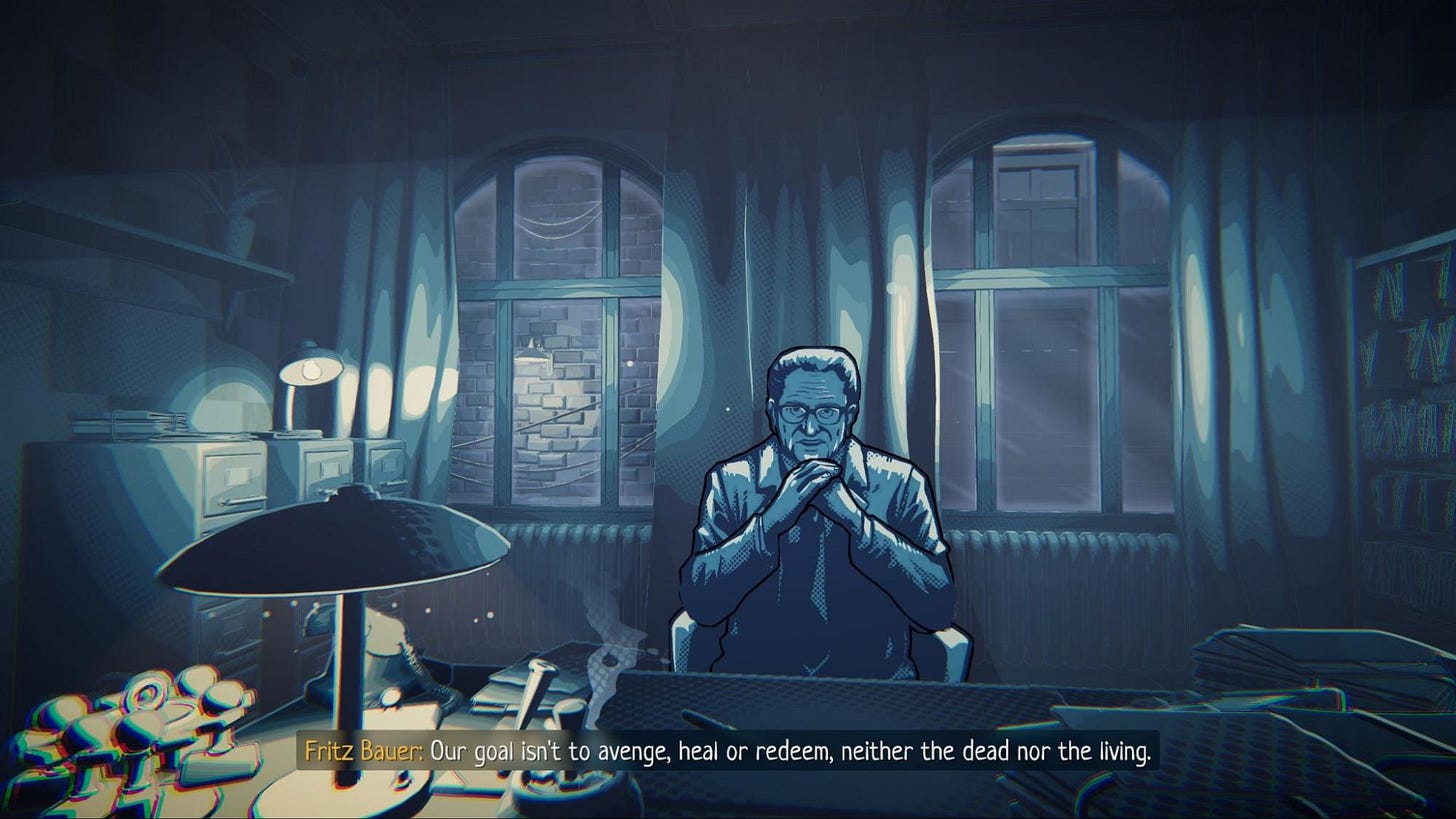

That was on me. I read everything by and about the man, watched and listened to every interview that could be found. The more I learned, the more fascinated I was: Bauer was so far ahead of his time, so progressive and despite his biography, he never seemed bitter or out for revenge but always trying to improve the German society while staying realistic and pragmatic. He saw the law and how it is applied not as a something standing for its own and always must be followed by the letter, but as a human made set of rules with the purpose of allowing everyone to live a life in peace and dignity and that laws that defy this must not be followed. (in a nutshell).

So for me, it was important that his perspective was conveyed in the game - rather than making up stuff about his private life. From all what we know, he was someone who never put himself in front but the cause - so that’s how we portrayed him in the game.

There were ideas on having him tell more about himself, his time in a concentration camp, etc., but we decided against it because we thought that he would never have done this. He wasn’t doing what he did because he was in a concentration camp, he was doing what he did because he thought it would increase chances that no one ever had to be in a concentration camp again.

CC: Beyond Bauer, the main cast of characters is fictional (or fictionalized), yet their personal backgrounds and interactions expand the historical texture of the game. What was your approach to adding fictional elements to the story?

Luca: If I were to answer that in a word, I’d say ‘careful'. It was very much a balancing act between providing our players with an immersive and entertaining experience, while ensuring it remained believable and respectful to the historical reality.

That last word is particularly important – realism and plausibility were a big focus with such additions. We wanted our fictional characters and events to be someone or something that could have actually lived, happened back then.

When written this way, their presence serves to bring that reality, that world, closer. Add that ‘historical texture’ you mentioned. It makes it more vivid, more lived in. Ironically, I’d say it makes it feel more real. Human.

The game puts a lot of effort into immersing the player—from thumbing through file cabinets, to building your case, to chatting with your coworkers over a cup of coffee—how do you approach the topic of building historical immersion and what ends does it serve?

Jörg: People should feel emotionally attached. We wanted to zoom in, to make you feel at home in the game and immerse in the game's world, relate to its characters.

Luca: It’s been 80 years since the war, 70 since the time of the game. For many, if not most people, that’s practically an eternity. A distant, different world you read about in books – or, quite often, lie about having read in books. It’s history, and history has the sad tendency to seem less ‘real’ than, say, whatever your plans are for Tuesday after work.

That’s where immersion comes in – making it feel more real, more personal. The cabinets, casefiles, coffee cups, all those little details that add texture, interactivity, involvement. The everyday tasks, problems, small-talk-filled conversations, they tie the player to the game’s world, making that history appear less... distant. Easier to understand, easier to feel.

CC: Fritz Bauer is most well known for the Frankfurt Auschwitz Trials. What motivated your decision behind exploring the lesser known cases taken on by his team?

It is much easier to distance oneself from one of the main perpetrators—a camp commander who has thousands on his conscience, or a doctor who performs experiments on people. We wanted to show crimes that are not so easy to distance oneself from – crimes where it is easier to imagine knowing someone who could commit them, or even finding oneself in a situation where one would act similarly. I am convinced that we can only prevent something like this from happening again if we understand the all-too-human characteristics that ultimately led to Auschwitz.

Fritz Bauer himself once said "The Auschwitz problem doesn't begin at the gates of Auschwitz-Birkenau. Someone had to bring people there. That means there were many, many perpetrators." We wanted to explore this - to show how the machinery of genocide was built through countless "smaller" crimes that were enabled by the same spirit that made Auschwitz possible.

CC: The game depicts the popular apathy, or even pushback regarding Nazi trials in post-war West Germany—some of it even hampers your ability to pursue your cases in-game. How do you think The Darkest Files strives to depict all of this context outside of the courtroom, and how it affects the way the law is handled and interpreted?

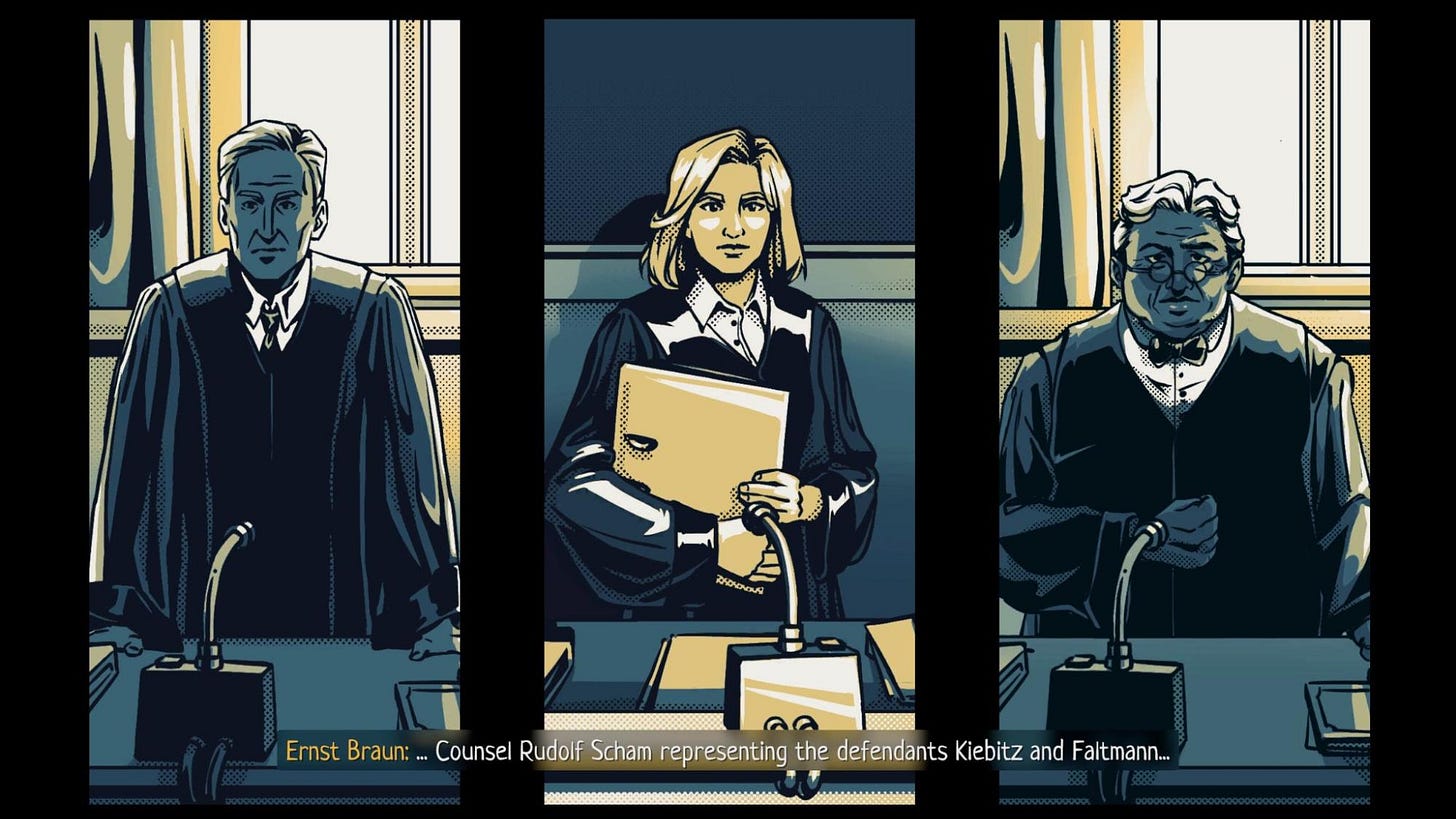

Fritz Bauer and his team not only fought legal battles in court, but also against a society that largely did not want these cases to be solved. You encounter witnesses who refuse to cooperate, acquaintances who ask you why you are “stirring up the past,” and institutional resistance that makes the search for evidence considerably more difficult. We wanted to show how many perpetrators had successfully reintegrated themselves into respectable society—they were judges, teachers, police officers—and how this network of complicity at all levels created obstacles to a genuine investigation.

In addition, the principle of “nulla poena sine lege” (no punishment without law) or the “prohibition of retroactive effect” or “prohibition of retroactive punishment” also applies to Nazi crimes.

It states that no one can be punished for an act that was not punishable at the time it was committed.

In the game, this is referred to primarily in the first case. It had to be proven to the perpetrators that their actions were wrong, even under Nazi law. This was surprisingly often the case—the Nazi state often motivated wrongdoing by not prosecuting it, but when it came to murder, they were particularly reluctant to put it into law—but it was difficult to prove, and prosecutors, who often had a Nazi past themselves, were not particularly motivated to initiate such complicated, time-consuming, and unpopular investigations.

CC: Post-war trials were quite unusual in that there was rarely evidence from the scene of the crime one could collect ten to twenty years after the fact. When building the cases and trials themselves, how did you go about deciding what to include as evidence, and to determine whether to weigh, for example, witness testimony or documents more heavily?

According to our research, such accusations had to be based almost exclusively on statements and files. Occasionally, crime scenes were visited to determine whether location X was visible from location Y or similar, but this remained the exception.

As in reality, a single statement is not sufficient for a conviction in the game; it must be corroborated by further evidence, whether in the form of documents or additional statements confirming the same.

Since we were able to read the court records but only had access to a few of the documents that had actually been used as evidence, and also for gameplay reasons, we came up with most of the documents used in the game ourselves.

In doing so, we allowed ourselves greater freedom to ensure that the whole thing worked in terms of gameplay and drama.

One exception to this are the pre-printed documents on the “shootings during escape,” which actually existed and we only modified slightly.

CC: You depict real historical dilemmas—like the failure of West German courts to convict unless “base motives” could be shown, or the need to prove guilt even under National Socialist-era legislation. At the same time, through the witness and defendant interrogations, we see wider ideological, psychological and social motivators come into play, but ones that are not necessarily prosecutable. What, in your words, was the driving philosophy behind understanding and depicting Nazi era crimes in The Darkest Files? What understanding do you wish the player to take with them after finishing the game?

Let me answer with two quotes:

Former Auschwitz prisoner Primo Levi:

“It happened, and therefore it can happen again: that is the core of what we have to say. It can happen anywhere.”

Fritz Bauer:

“We cannot make heaven out of earth, but each of us can do something to prevent it from becoming hell.”

To put it in my words: Humans are capable of turning the worst imaginable scenarios into reality, but they are also capable of recognizing when this is happening and stopping it. And the latter is what we must do.

CC: The game covers a topic where many perpetrators were able to slip through the cracks of the legal system. How do you approach balancing a historical depiction of the court system and its limitations with creating an enjoyable game for the player?

By allowing success and impact within these limits.

In doing so, we allow players in the game to make “better” judgments than those made in reality.

CC: The in-game Bauer insists that his team’s project is “to see justice done. To uphold the law”. At the same time, he believed that trials must provoke political and ethical reflection, not merely punishment. How does your game invite players to reflect while pursuing the game’s victory-state of a successful sentencing?

I don't want to spoil too much of the story, but I hope that's what it does.

CC: Paintbucket Games has already explored the effects of National Socialism from a variety of perspectives in your previous titles. What is one aspect you still wish to explore?

I could imagine a political simulation of right before the Nazis take power could be interesting - especially, when, different from reality, you might be able to save democracy.

The Darkest Files offers a new perspective on what historical games can be. It is uncompromising and clear with the message it wants to deliver to its playerbase, who might never pick up a trial transcript or a scholarly history of post-war justice. Yet, it trusts them enough to shoulder them with a responsibility, not only as the player in achieving the game’s goal, but as a person reflecting on the real beating heart of National Socialism: the familiar resentments beyond the shocking and alienating brutality of the camps.

The game makes the player engage with the historian’s craft, in digging through archives and files, much as the developers did for their research. It also makes gamers confront the two purposes of law: whether it should be an internally logical, closed system to resolve concrete questions, or an expression of certain fundamental rights and dignities afforded to all.

The interview makes even clearer Bauer’s role as the emotional and moral crux of the game. It was, in fact, explicitly built around this idea. Through him, the game can foreground the uncomfortable truth that trials are never purely legal exercises. They are also political, social, and cultural events that leave a mark on society long after a verdict has been reached.

Games like The Darkest Files are vital because they bother to ask “how the machinery of genocide was built through countless 'smaller' crimes that were enabled by the same spirit that made Auschwitz possible”. Such a lesson may be valuable in a time like ours, where “never again” is allegedly used to justify rather than prevent a genocide. The game helps us remember that the horror of the death camps was the final step in a long process.

What a fascinating article—and game. I love that a whole new audience will be thinking about history and the cost of personal choices in such an engaging way.

Just exposing the corruption

https://open.substack.com/pub/emmettcorbett/p/the-rot-within?utm_source=share&utm_medium=android&r=49zugr