A Life Criminalized: The Romani and Vagrancy in Imperial Russia

“Incapable of settled life” How Vagrancy Laws Criminalized Being Romani

At Curing Crime we are excited to feature our first guest post. The main author of this piece is Jovan Ilijev. Christian and Lucas are secondary authors.

During the 1800s, the upper echelons of Russian state and society were convinced that the modernization of the nation should be their paramount objective. This meant the rational reordering of the country, a project inspired by the Enlightenment and started by Peter the Great (В. Н. Шайдуров). In the 19th century, that reordering was increasingly aimed at making the state’s presence known to its subjects in their daily lives. Russia’s conquests left a medley of people-groups, such as the Roma, living under their own social structures and administrative systems inside the empire’s borders. This was a complicated and undesirable state of affairs for any centralized government. To overcome these challenges, future Tsars sought to homogenize them under Russia-wide law and governance. The Roma in particular were singled out for their otherness. The Romani covers an umbrella of ethnic groups originating in Northeastern India that settled along Iran, Anatolia, and Central and Eastern Europe, but maintained distinct cultural and social practices due to marginalization.

The rational organization of society divided people into clearly defined groups. For the state administration, the rational state of existence was that of the sedentary peasant, the serf. They were situated in one place, farmed one plot, beholden to one tax collector, and to one conscription officer when the need arose. To turn the Roma into serfs, the state first had to sedentarize them. And to sedentarize the Roma they had to first criminalize their nomadism, or ‘vagrancy’ as it was known to them.

Who Are The Roma?

The Roma of Russia’s western governorates were mostly itinerant artisans and entertainers that plied their trades among the settled population, but whose mode of living was anything but similar. Their place as specialty artisans and entertainers in Russian society, from coppersmiths to horse traders to shoemakers, had them rely on the patronage of non-Roma (Shaidurov). They were deeply integrated into both the rural and urban economic life wherever they were situated. Despite this, throughout the 19th century their existence was problematized. The “remedies” to their non-standard living arrangements were sedentarization programs, meant to homogenize Roma populations both socially and economically with the serfs they lived amongst.

The solution proposed to many Roma was quite befuddling to them, as they were not aware of any problem to begin with, making good money with their trades. That is to say, if there was no coercive “or else” administered by the courts and police, there would be no sedentarization, as there was no particular reason for these nomadic groups to stay in state sponsored villages. More often than not, their nomadic activities afforded them more economic opportunity, less tax and conscription burdens, and a higher quality of life.

Criminalizing Vagrancy, Forcing Sedentarization

The case of the Roma brings up important questions about the ends criminalization serves. What motivated vagrancy laws? There was certainly a moral component, in that ‘vagrants’ already have a charged implication that was only compounded by ethnic stereotypes of Roma as unproductive layabouts. But if your lifestyle is criminalized, then your legal options are naturally pushed closer to the state’s watchful eye, whether in the barracks, the jailhouse, or the government-erected villages. Andrew A. Gentes argued that:

“vagabondage is best understood as a Foucaldian knowledge technology functioning within a modern disciplinary apparatus…the conflicts produced may be said to consist for the most part of decision makers trying to impose order on perceived deviants as part of a normalizing process, all of which renders the vagrant as much an invention of modern technology as the internal combustion engine (Gentes).”

The charge most often used against non-compliant Roma was that of “vagrancy”, a practice that was increasingly seen in the 18th and 19th centuries not as a personal choice, or a state of being, but a crime to be persecuted and corrected by the instruments of the state. Administrators saw sedentarization not only as a practical policy, but a humanitarian cause to uplift these communities from what they incorrectly saw as the root of their destitution.The ‘invention’ of criminal vagrancy lets us see one of the many ways the modern state attempted to change the societies it governed, and how those societies resisted.

Development of Russian Vagrancy Laws

Like most other things, the attitudes of the 19th century Russian ruling class towards vagrancy have their origins in Peter the Great. In 1649, a new legal code was brought in, that fully curtailed serf rights to free movement. Prior to Peter the Great, however, the perception of vagrancy was still heavily governed by Christian values.

In the 16th and 17th centuries, Church and state sponsored almshouses institutionalized charity towards vagrants. Saint Maximus the Greek idealized vagrants as being closest to God and wrote against their persecution. Others, such as Epiphanius Slavinetsky, were quick to point out the difference between deserving and undeserving vagrants.

Vagrancy was not considered a ‘normal’, permanent, or desirable condition, but neither was it seen as a crime or sin to be rectified by coercive measures. The nature of these disagreements on the ‘deservedness’ of alms tells us a lot about how vagrants were framed: discussion of undeserving vagrants did not mention criminal punishment, instead they were focused on simply denying them Church aid or having them be put to work.

Peter the Great broke with this understanding by criminalizing begging, an activity associated with vagrancy. State discourses linked vagrancy with criminality. The state deployed its forces to coerce vagrants into returning to their plots or engaging in ‘socially useful’ work ( Шляков). “The vagrant lost his “patron” [in the Church] and has to bear responsibility before the social institution…[t]he religious approach finally gives way to the social one, and the need and plight of the beggar is considered not in the context of the path to eternity, but on the basis of specific problems of society (Шляков).”

Vagrancy’s criminalization opened up new administrative and judicial procedures that allowed vagrants to be conscripted into the military or exiled either as colonists, or forced labor to Siberia (Gentes). In 1832, the “Laws about Estates” recognized various social estates, or social classes, that all Russian subjects had to belong to. These estates had various rights and obligations, most pertinent of which being taxes (which nobility and clergy were exempt from). The more vagrants there were, the less tax revenue could be extracted from the populace, making their ‘normalization’ into sedentary peasant estates more and more of a focus of the government.

Russian Visions of the Roma

While the Russian state perceived the Roma way of living as undesirable and problematic, other members of high society had different perceptions of their lifestyle and culture.

Official reports speak of Roma groups simply “wandering” and leading economically unproductive lifestyles (Crowe). The centuries-old practices and defined migration patterns of Roma craftsmen were portrayed as aimless meandering. In correspondence and official decrees, high level Russian officials express their frustration towards Roma populations for seemingly not knowing any better, costing the state potential dues and bodies for the army.

There was also a centuries-long fear within government circles of vagrancy in general that motivated its criminalization. Runaway serfs bolstered the ranks of peasant rebellions such as that of the Khlopko Rebellion, conflating the image of the vagrant with that of bandit and the rebel (Gentes). The reasons the Roma and the Russian serfs turned to vagrancy were quite different, they were nonetheless painted with the same brush.

At the same time, in the 19th century, vagrants and Roma were exoticized. Famous bands such as the Sokolovsky Gypsy Choir entertained at noble and imperial courts in St. Petersburg and Moscow. They were viewed as more ‘authentically Russian’ than the French compositions that dominated before the Napoleonic Wars. Some members of the gypsy choirs even married into high society (Scott).

Alexander Pushkin’s romantic poem, The Gypsies, created the canonical popular image of the Roma as a kind of noble savage—hot-blooded free spirits, owning little, yet enjoying everything. Nikolai Leskov’s novel, The Enchanted Wanderer portrays the vagrant protagonist in many ways: first, as a shifty individual exploiting Christian good-will and escaping the law, second as an adventurous, restless, and free spirit, and third as a man loyal to the Tsar and Holy Russia (Seliazniova). The perceived freedom from the law that vagrants and Roma enjoyed in the popular imagination enamored the literati, who sought a counterpoint to the Russia of ‘dead souls’ that they critiqued in their writings.

Nevertheless, the authority of poets and that of governors seldom collided. The royal decree of March 1, 1766 states: “Belgorod province is filled with gypsies; although they are paying taxes, this small revenue to the treasury cannot be compared with the benefits that could come from this people, if it were gathered in one place and taught farming (Smirnova-Seslavinskay).” Similar sentiments would echo in official writings into the 1800s.

The Roma and Russian Policy

The pattern of instability and coercion that marked Roma settlement began prior to their existence within Russia. In the 16th century, the Roma suffered several expulsions in Poland-Lithuania, fleeing to Russia (Smirnova-Seslavinskay). It was not until the late 18th century that Russia absorbed a significant Roma population in modern-day Belarus. This was almost immediately followed by policies to integrate them into ethnic majority communities through sedentarization (Shaidurov).

In the 1750s, taxation was collected by ‘gypsy chiefs’ responsible for their community that, in turn, were granted relative autonomy (Crowe). By the end of the 18th century however, the Petrine reforms had by now thoroughly calcified—the local potentates were replaced by the Russian state and its estate system. In it, all but the most affluent Roma were classified as state peasants—serfs directly owned by Russia—and later in 1812 had to register themselves to facilitate taxation (Crowe). What the state was attempting was to typologize and normalize the pluralistic Roma into categories that they could more easily understand and act upon (Dunajeva). These efforts made it difficult for the Roma to lead their lifestyles.

Sedentarization

Russian officials saw their laws as an attempt to mold Roma behavior and produce socially useful outcomes, as defined by the officials themselves. Even so, total enforcement of the estate system proved difficult due to the heterogeneity of the community spread between geographical area, religion, and state classification. Combined with the Romas’ active defense of their lifestyle, the administration had great difficulty mapping the community for conscription and taxation. To alleviate these issues, at various moments officials embarked on a wide ranging sedentarization policy.

This policy, in essence, involved attempting to shape society so that it better fit the State’s model, rather than changing their model to better fit society (Scott). What was the State’s rational reaction to seeing landless, ‘wandering’ peoples whose value was impossible to capture on paper? To integrate them into more legible economic activity where taxes and men could be more efficiently levied. These measures unwittingly uprooted community ties and social safety nets, which were invisible to the state (Scott).

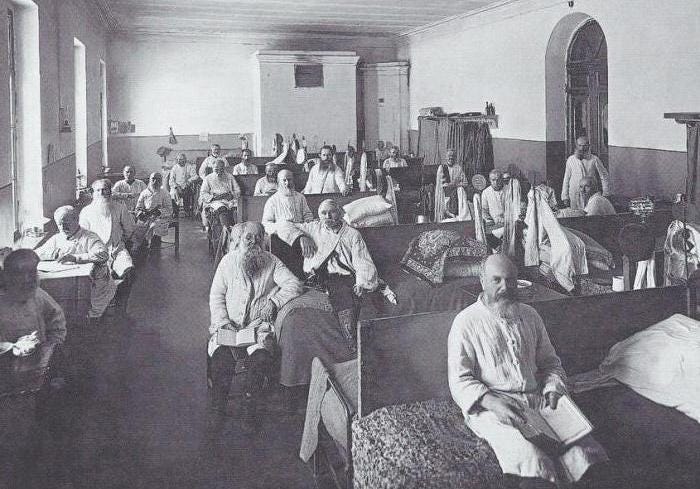

The authorities gave Roma state-owned (and monitored) plots and allowances so that they could sedentarize, assuming they would see this as a way to improve their often dire economic conditions. In 1837, the Ministry of State Property was specifically created to prevent vagrancy by allotting land. It was still viewed as a grave social problem, but now the method to combat it was not only criminalizing the act, but also providing the means of subsistence farming (Тюрин). This is not to imply that the stick was laid aside entirely in favor of the carrot. The Count Vasily Perovsky suggested branding all Roma men aged 17-60 in the state villages to discourage any return to vagrancy (Тюрин).

The families that volunteered were usually amongst the poorest—the better off Roma had ways of acquiring freedom of movement through purchasing a merchant estate or outright bribery. Examining one of these schemes in Grodno, western Belarus, we see several families abandoning their plots to return to their previous lives, with the record stating that “[Gypsies are] incapable of settled life” (Шайдуров).

In reality, it was because their traditional economic activities generated more wealth, especially since many of these families had no experience farming. The myopic focus on rent extraction failed to birth productive citizens, what it did instead was sever economic ties while also heightening tensions. The Roma that stayed willingly, clashed with peasants interested in the state land ( Шайдуров). Oftentimes, the government did not properly instruct Roma in farming, or provided them marginal land that was incapable of sustaining their families, prompting petitions by the Roma themselves to be resettled elsewhere (Тюрин). Lower level officials lamented the exaggerated expectations of their superiors, and had few pretensions that a quick and forceful sedentarization would solve their problems: “in order to accustom them [Gypsies] to a settled life, and even more so to crafts and literacy, it takes time, not strictures, which can do more harm than good” (Smirnova-Seslavinskaya).

Criminalization

Numerous campaigns to have Roma willingly sedentarize were met with little success, prompting the state to develop more coercive corrective measures. The aforementioned 1812 registration of Roma was qualified with the fact that any who failed to register would be charged under vagrancy laws. Once registered as a state peasant, they had the same movement restrictions as other serfs. They had to register—and pay for—passports authorizing freedom of movement within a limited area and time (Smirnova-Seslavinskaya,). The majority of the community would either acquire passports legally, through bribes; would leave illegally; or would not register at all, to continue living nomadically. For those Roma that had settled in state villages, anyone that was caught leaving would be prosecuted on the charge of vagrancy, according to Nicholas I’s Imperial Decree of the 13th of March, 1839 ( Шайдуров). Even this threat did little to fully stop Roma from abandoning or renting out their plots.

In addition, as registered serfs, the Roma were subject to the same conscription requirements as the rest of the population. In 1832, the law “On the resolution of the question of what to do with vagrants between 17-20 years old and 20-25 years old” was introduced, making explicit the policy of sending Roma arrested on vagrancy charges to the military. Russian policy created a win-win situation: if the Roma settle, they will be properly kept track of and conscripted; if they do not, when they are caught, they can be sent off to the barracks regardless. Women were instead regularly sent to factory work, where they would live integrated into sedentary urban communities (Shaidurov and Novogrodsky).

Criminalization did not stop Roma lifestyles, but by criminalizing their social existence, the authorities were able to extract tax from those who settled, but also regular fees and fines from those who did not. Another fact that points to this reality is that vagrancy charges were levied on Roma usually only when they had acquired significant debt to the state. The seeking of fines was a profitable enough venture that police officers would intentionally incite these crimes to be able to collect on them, to such an egregious extent that, in 1819, the entire Ministry of Police was shut down (Crowe). Actions such as these, point to the fact that while vagrancy laws did serve a fiscal extractive purpose, it was far from the only one.

Suffice to say, the attempt to ‘modernize’ them was often counterproductive, leading to excess expenditure with few lasting results. While criminalization allowed Russia to squeeze men and money out of Roma communities, it had significant difficulties in permanently sedentarizing them. The state failed to create a compelling economic alternative to service nomadism, making sure that segments of the Roma population would keep to their traditional lifestyles despite the hefty risks if they were caught.

In a wider sense, this historical case puts into question the material and ideological factors of what is determined to be a crime, and who determines it. The ‘what’ and ‘who’ necessarily dictate the way a society approaches solving those crimes: cracking skulls, issuing fines, setting up social programs, or maybe putting into doubt whether it is even a crime at all.

This article was mostly written by Jovan Ilijev. Jovan did the research and develop the argument. Christian and Lucas helped Jovan with the framing, editing, and structuring of the article. We agreed to share authorship.

Jovan is a graduate of Global Studies from Pompeu Fabra University.

Sources

В. Н. Шайдуров, “Цыгане Белорусских Губерний и Землеустроительная Политика На Рубеже 1830–1840-х Гг.,” Журнал Фронтирных Исследований 6, no. 3 (September 16, 2021): 96–97, https://doi.org/10.46539/jfs.v6i3.259.

Vladimir N Shaidurov, “Gypsies in the Russian Empire: Theories and Practices Addressing Their Situation during the Eighteenth and First Half of the Nineteenth Century,” Romani Studies 28, no. 2 (2018): 203–5, https://doi.org/10.3828/rs.2018.8.

Andrew A. Gentes, “Vagabondage and Siberia: Disciplinary Modernism in Tsarist Russia,” in Cast out: Vagrancy and Homelessness in Global and Historical Perspective, ed. A. L. Beier and Paul Ocobock, Ohio University Research in International Studies. Global and Comparative Studies Series, no. 8 (Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 2008),

Алексей Шляков, “К ИСТОРИИ РУССКОГО БРОДЯЖНИЧЕСТВА XVII–XIX ВЕКОВ,” Тюменский Индустриальный Университет, n.d., 288–90.

Marianna Smirnova-Seslavinskaya, “Service Nomadism of the Roma / Gypsies in the Russian Empire: A Social Norm and the Letter of the Law,” Ab Imperio 2021, no. 1 (2021): 64, https://doi.org/10.1353/imp.2021.0003.

Arianna V. Smirnova-Seslavinskaya, “Formation of the Romani Population of Russia: Early Migrations,” Observatory of Culture, no. 1 (February 28, 2015): 136, https://doi.org/10.25281/2072-3156-2015-0-1-134-141.

Vladimir N. Shaidurov, “Gypsies of the Belarusian Provinces and Land Management Policy at the Turn of the 1830s-1840s,” Journal of Frontier Studies 6, no. 3 (September 16, 2021): 99, https://doi.org/10.46539/jfs.v6i3.259.

David Crowe, A History of the Gypsies of Eastern Europe and Russia, 2nd ed., updated and rev (New York: Palgrave/Macmilan, 2007)

Jekatyerina Dunajeva, Constructing Identities over Time : “Bad Gypsies” and “Good Roma” in Russia and Hungary (Budapest: Central European University Press, 2021)

James C. Scott, Seeing like a State

А. С. Тюрин, “‘цыганская Проблема’ в Деятельности Ведомства Государственных Имуществ в Нижегородской Губернии (1839-1866),” Нижегородский Институт Управления РАНХиГС, no. 3 (2018): 43, https://doi.org/10.17072/2219-3111-2018-3-42-53

Шайдуров, “Цыгане Белорусских Губерний и Землеустроительная Политика На Рубеже 1830–1840-х Гг.,” 100.

Vladimir N. Shaidurov and Tadeush A. Novogrodsky, “The Gypsies and Military Service in the Russian Empire in the Second Half of the 18th - First Half of the 19th Century,” RUDN Journal of Russian History 19, no. 4 (December 15, 2020): 844–45, https://doi.org/10.22363/2312-8674-2020-19-4-838-850.